Mapped: How climate change affects extreme weather around the world

18 November 2024

By Robert McSweeney and Ayesha Tandon

Design and development by Kerry Cleaver, Tom Pearson and Tom Prater

In 2004, a trio of researchers published a study that accomplished something never seen before. They calculated the specific contribution that human-caused climate change made to an individual extreme weather event.

The extreme event in question was the European heatwave in the summer of 2003. Week upon week of extreme heat had a devastating impact, killing more than 70,000 people across the continent.

The scientists worked out that human influence had at least doubled the risk of such an extreme heatwave occurring. The findings made headlines around the world.

The study kick-started the scientific field of “extreme event attribution”.

Attribution studies calculate whether, and by how much, climate change affected the intensity, frequency or impact of extremes – from wildfires in the US and drought in South Africa through to record-breaking rainfall in Pakistan and typhoons in Taiwan.

To keep track of this rapidly growing field of research, Carbon Brief has mapped every published study on how climate change has influenced extreme weather.

Further reading:

This latest iteration of the interactive map (below) includes more than 600 studies, covering almost 750 extreme weather events and trends.

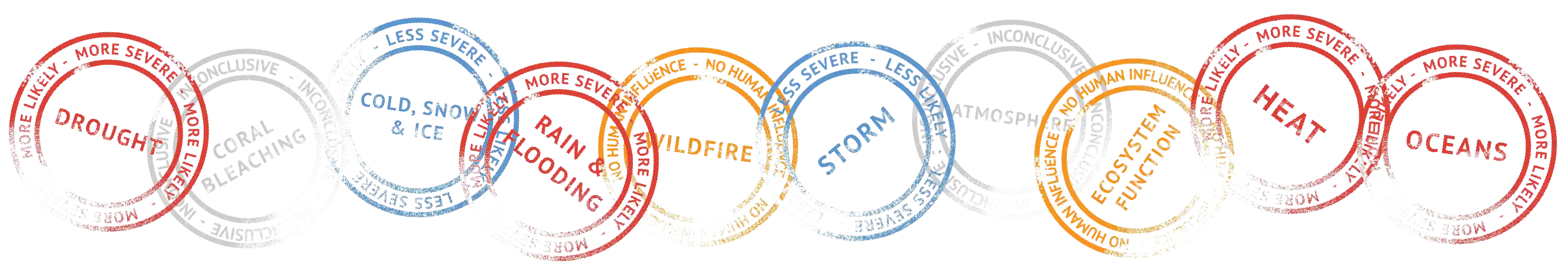

Across all these cases, 74% were made more likely or severe because of climate change. This includes multiple cases where scientists found that an extreme was virtually impossible without human influence on global temperatures.

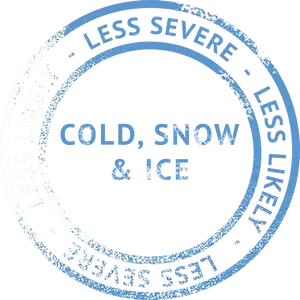

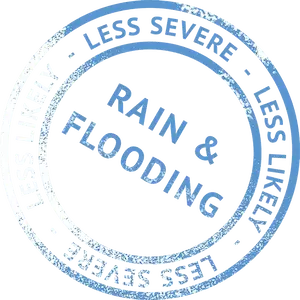

Around 9% of the events and trends in the map were made less likely or severe by climate change.

This means that, overall, 83% of the events and trends included in the map were found to have been influenced by human-caused climate change.

In the remaining 17% of cases, the studies either found no human influence (10%) or they were inconclusive (7%), often due to insufficient data.

First published in July 2017, this is the sixth – and most comprehensive – update to Carbon Brief’s map.

Studies of almost 750 events and trends reveal the impact of climate change on extreme

weather.

Studies of almost 750 events and trends reveal the impact of climate change on extreme

weather.

Explore the studies either via the map or by the panel of controls below.

Switch

How did climate change influence the weather event:

More severe or likely | 547 |

Had no influence | 71 |

Less severe or likely | 64 |

Inconclusive | 53 |

Extremes across the world

In total, the map (above) contains 735 extremes from 612 studies. This is a combination of individual events, such as the Australian bushfires of 2019-20, and trends of how extremes are changing, such as a 2020 study into marine heatwaves over the past four decades.

Australian bushfires, 2019-20

Event type

Wildfire

Finding

More severe or more likely to occur"[W]e find that climate change has induced a higher weather-induced risk of such an extreme fire season. This trend is mainly driven by the increase of temperature extremes."

Marine heatwaves, 1981-2017

Event type

Oceans

Finding

More severe or more likely to occur"We show that the occurrence probabilities of the duration, intensity, and cumulative intensity of most documented, large, and impactful MHWs have increased more than 20-fold as a result of anthropogenic climate change."

Where a single study covers multiple events or locations, these have been separated out into individual entries on the map (where possible).

Such is the sheer quantity of attribution studies, the new map displays them in regional summaries, rather than individual events or trends. (The regions follow those used by the UN, except the UN’s “Europe and Northern America” region has been divided into two.)

By default, the map displays the data by attribution result.

The circles in each region indicate how many events and trends have been made more (red) or less (blue) severe or likely by climate change.

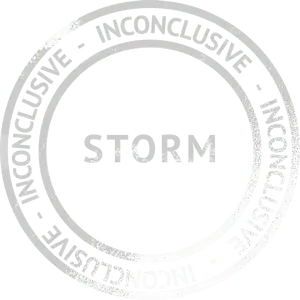

Yellow indicates extremes where no human influence was found, while grey shows studies that were inconclusive.

To explore the data for a specific region, click the relevant circles on the map. This reveals a summary page and a link to explore all the studies related to that part of the world.

Across all cases, 74% were found to have been made more likely or severe because of climate change. More than a third of these are heat extremes, which are generally the most straightforward events to link to a warming world.

High rainfall in Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Zambia, February 2018

Event type

Rain & flooding

Finding

Decrease, less severe or less likely to occur"This multi-method study of high precipitation over parts of Mozambique, Zimbabwe and parts of Zambia in February 2018 indicates decreased likelihood of such events due to climate change, but with substantial uncertainty based on the used observations and models."

Around 9% of the events and trends in the map were made less likely or severe by climate change. Unsurprisingly, this category is dominated by blizzards and cold extremes, but there are also cases where climate change has lessened the chances of other extremes – such as the high rainfall event in February 2018 over south-east Africa.

The remaining cases are extremes where scientists either identified no human influence (10%) or where the findings were inconclusive (7%).

(It should be noted that these figures are not representative of all extreme weather events as only a small fraction have been subject to an attribution study. In addition, some of the events included in the map have been the subject of more than one study.)

The map can also be viewed by event type, which groups the data into seven categories: heat (red), rain and flooding (navy blue), drought (yellow), storm (purple), cold, snow and ice (blue) and other (grey).

To delve into the individual extremes, click “explore all cases” in the map legend or choose a specific country from the dropdown list. A searchable table is also included at the end of this article.

Profile 01

The United States

There are more than 103 attribution studies focusing on events in The United States. 72 studies found that climate change increased the severity or likelihood of the event. Explore the studies for The United States

Evolving methods

Following the first extreme event attribution study in 2004, the research field has rapidly gained momentum – with many more scientists and institutions carrying out studies and new methods being developed.

And what started as a trickle of studies has turned into a flood. In the 10 years following that first scientific paper, around 50 more were published. In the 10 years after that, the number has risen tenfold by more than 500.

There are various ways of carrying out an attribution study, but scientists commonly use climate models to simulate an extreme event in the current climate and compare them with idealised model runs of that event in a world without human-caused warming. The difference between the two sets of simulations indicates how the likelihood or severity of that extreme event has changed.

The evolution of attribution methods over the past two decades is explored in detail in an accompanying Carbon Brief article.

The chart below reveals that the most-studied extremes are related to heat (28%) and rainfall and flooding (24%), which together account for more than half of the events and trends in the map. The next-largest group is for drought (14%), followed by storms and cold, snow and ice (both 8%).

Event types

One of the most significant developments seen in attribution science is the advent of “rapid” studies.

In 2015, the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative was founded, which streamlined the attribution process in order to produce results within days of an extreme event occurring.

The team uses a standard, peer-reviewed methodology for their analysis, but does not routinely publish the results in formal journals – instead publishing them directly on the WWA website as soon as the analysis is complete.

This has allowed scientists to answer the question of how climate change contributed to an extreme event in the immediate aftermath, rather than months later.

For example, on 30 July, heavy rainfall in Kerala, India, triggered massive landslides that killed hundreds of people. Within two weeks, WWA was able to show that human-caused climate change had made the extreme rains 10% heavier.

Heavy rainfall behind Kerala landslide, July 2024

Event type

Rain & flooding

Finding

More severe or more likely to occur"The available climate models indicate a 10% increase in intensity."

The Carbon Brief map includes WWA studies as well as those from selected other groups, including the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London and the UK Met Office. (See methodology at the end of this article for more details.)

Another recent advance is “impact attribution”, which quantifies the social, economic and/or ecological impacts arising from the influence of climate change on extreme weather.

In this latest iteration of the map, Carbon Brief has created a specific category for all of these studies. These include, for example, research showing how climate change increased the risk of people being displaced by Tropical Cyclone Idai when it hit Mozambique in 2019, and a study showing that 370 deaths during Switzerland summer of 2022 "could have been avoided in absence of human-induced climate change".

Human displacements from Tropical Cyclone Idai, 2019

Event type

Impact

Finding

More severe or more likely to occur"Our main estimates indicate that climate change has increased displacement risk from this event by approximately 12,600-14,900 additional displaced persons."

Deaths during Switzerland summer heatwave, 2022

Event type

Impact

Finding

More severe or more likely to occur"We estimate 623 deaths due to heat between June and August 2022…we find that 60% of this burden could have been avoided in absence of human-induced climate change"

Uneven spread

Even a cursory look at the Carbon Brief map reveals the uneven spread of studied extremes across the world, with the vast majority in the global north.

The cases included in the map are dominated by extremes in Europe (22%), eastern and south-east Asia (22%) and northern America (19%). In contrast, relatively few of the studied extremes are in central and southern Asia (5%), Oceania (1%) and northern Africa and western Asia (1%).

Region breakdown

There are a number of reasons for this, including a lack of weather data and monitoring of extremes in many developing countries. Another factor is that scientists and their institutions that conduct attribution research are often themselves based in global-north countries.

This imbalance is something that many attribution scientists are trying to address, putting a greater focus on extremes in countries that are often overlooked.

What is also noticeable in this latest iteration of the map is the large number of studies examining extremes in China, following record-breaking heatwaves, severe drought and deadly rainfall events in recent years.

In total, 114 extremes and trends in China have been the subject of an attribution study – making up 16% of all the cases included in the map. More than 70% of them have been published in the past four years.

Profile 02

China

There are more than 114 attribution studies focusing on events in China. 88 studies found that climate change increased the severity or likelihood of the event. Explore the studies for China

Use the searchable table below to see all extremes and trends for a specific country, and/or use the dropdown lists to select specific regions or types of extremes.