The past few years have seen an explosion in major economies and businesses seeking to cancel out their polluting activities by paying for emissions to be reduced elsewhere – a practice known as “carbon-offsetting”. ← (Clicking links with a will display the full glossary term).

The surging demand for carbon offsets has given rise to a largely unregulated industry where businesses and countries can pay brokers to cut emissions somewhere else in the world.

This is often achieved through forest-protection schemes – which are meant to reduce emissions by preventing deforestation – as well as other methods, such as tree-planting and distributing low-carbon cookstoves in the developing world.

Investigations into individual carbon-offset projects by journalists and non-governmental organisations have revealed that many of these schemes can come with devastating impacts for Indigenous peoples and local communities. Reporting has also found that many schemes overstate their ability to reduce emissions.

By trawling through original media reports published over the past five years and scanning the world’s most comprehensive environmental conflicts database, Carbon Brief draws these stories together for the first time to create a detailed picture of the breadth and scale of the impacts of carbon-offset projects around the world.

More than 70% of the reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects causing harm to Indigenous people and local communities.

Indigenous peoples have been forcibly removed from their land because of carbon-offsetting in the Republic of the Congo and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Brazilian, Colombian and Peruvian Amazon, Kenya, Malaysia and Indonesia, according to reports analysed by Carbon Brief.

Cases include one where Indigenous peoples were allegedly threatened with guns and another where a publication accused a carbon-offset developer of planting on top of the graves of Indigenous peoples.

Some 43% of the reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects overstating their ability to reduce emissions.

This includes accusations of fossil-fuel companies knowingly using tactics to inflate the offsetting potential of their projects and one alleged case of a California carbon-offset company selling to polluters even after the trees in its forest protection scheme had been burnt down by a wildfire.

Mapped

To understand the impacts of carbon-offsetting around the world, Carbon Brief conducted an in-depth search of news reports and investigations published by newspapers, broadcasters and online media between August 2018 and August 2023. Carbon Brief specifically looked for original stories detailing the impacts of individual carbon-offsetting projects.

Stories were found using the media search tool Factiva, as well as through supplementary research. Carbon Brief analysed articles published in English and Spanish.

This information was combined with case studies on the impacts of carbon-offset projects from the past five years from the Environmental Justice Atlas. The EJ Atlas is a comprehensive database of environmental conflicts around the world maintained by researchers at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

The search revealed 61 original stories detailing the impacts of individual carbon-offset projects in regions stretching from Scotland and the Republic of the Congo to the Brazilian Amazon and the Australian outback.

The impacts recorded by Carbon Brief included harm to Indigenous peoples, local communities, food production and nature, as well as illegal land use. Carbon Brief also examined cases of individual offsetting projects overestimating their ability to reduce emissions.

(It is worth noting that media and civil society groups are more likely to investigate and report on negative impacts given their duty to hold organisations accountable.)

Some 72% of the reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects causing harm to Indigenous peoples and local communities.

And 43% of the reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects overstating their ability to reduce emissions.

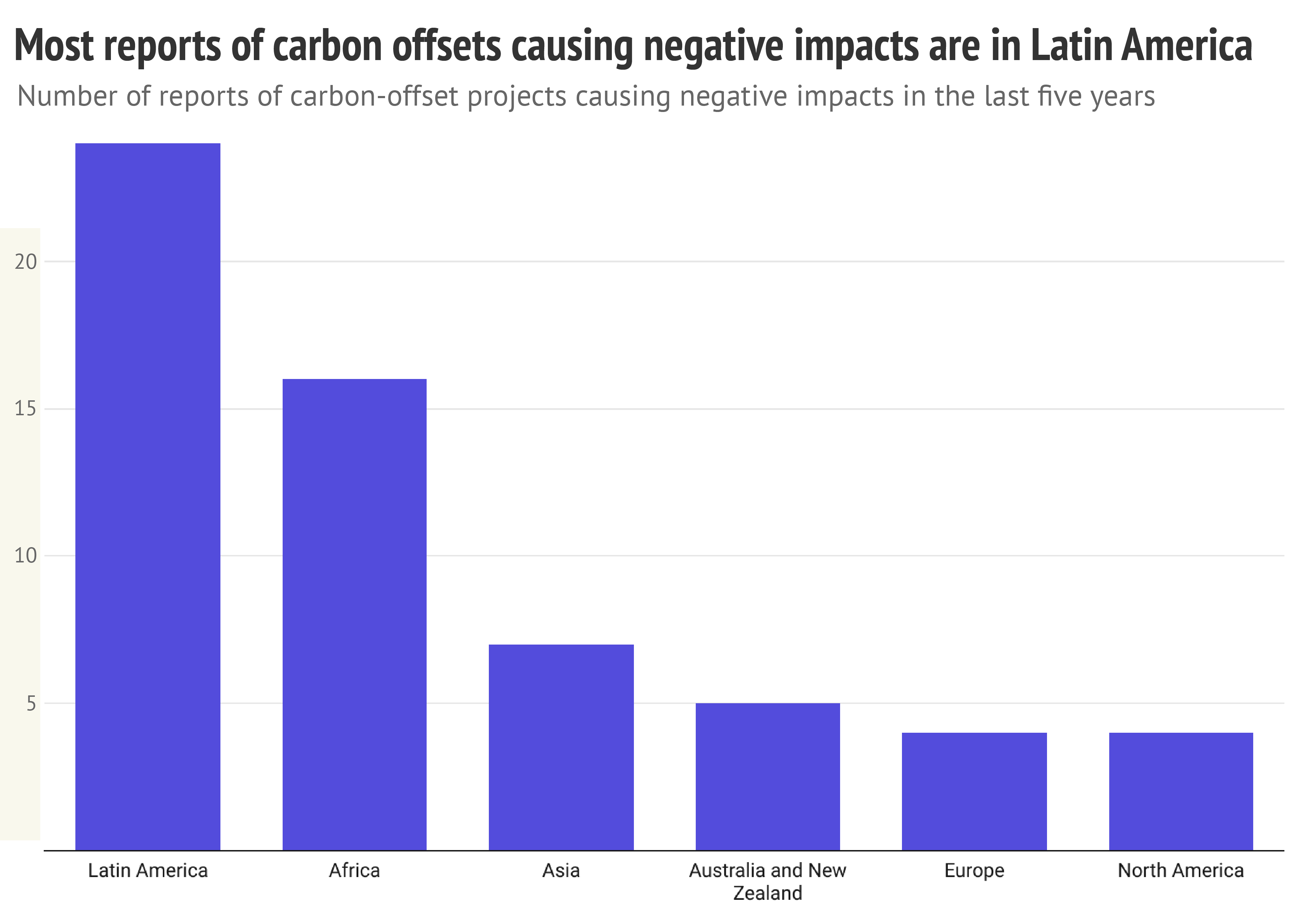

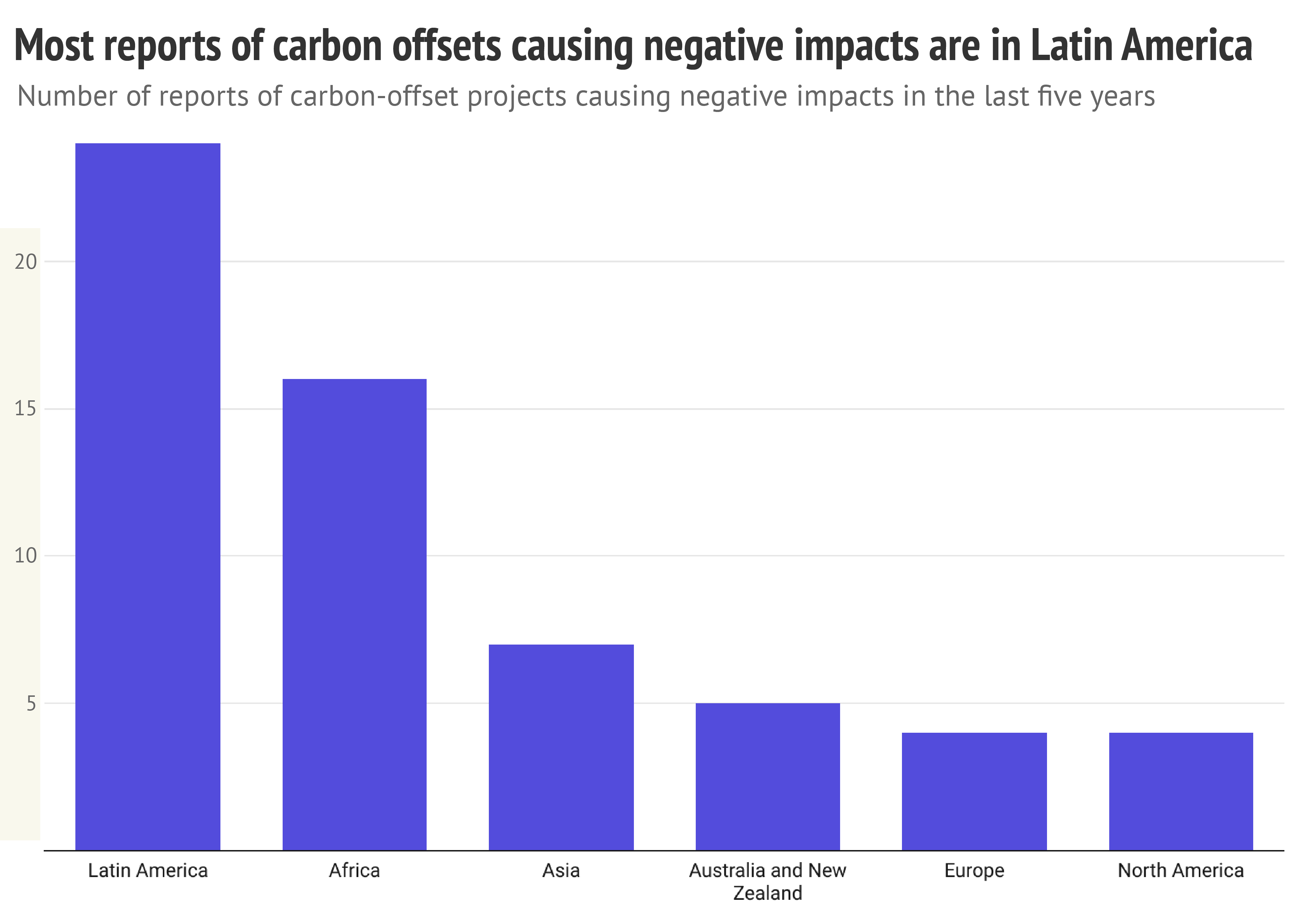

Most reports of carbon offsets causing negative impacts were located in Latin America (24), followed by Africa (16), Asia (7), Australia and New Zealand (5), Europe (4) and North America (4). Out of the Latin American cases, 20 were located within the Amazon rainforest.

Number of reports of carbon-offset projects causing negative impacts in the last five years for different world regions. Credit: Carbon Brief.

Number of reports of carbon-offset projects causing negative impacts in the last five years for different world regions. Credit: Carbon Brief.Carbon-offset projects are typically developed and marketed by specialist companies and consultancies. They use their projects to generate “carbon credits” – each representing one tonne of CO2 – which they sell to polluting countries and companies, who use these to offset their own emissions. (Credits have to be verified by third-party registries.)

Over the past five years – the timeframe of this analysis – the number of carbon credits being sold to businesses looking to offset their emissions so they can claim to have met climate targets has exploded.

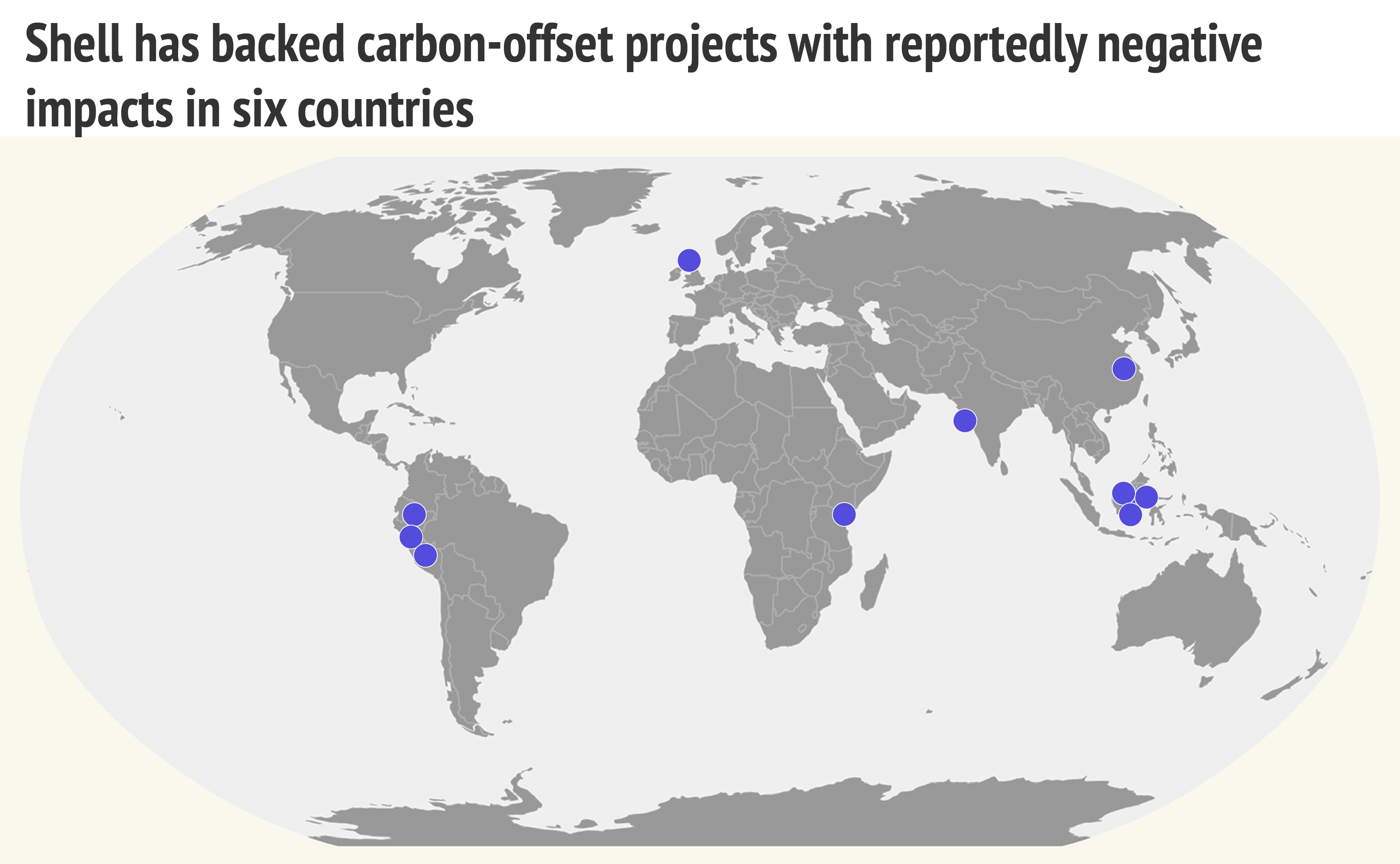

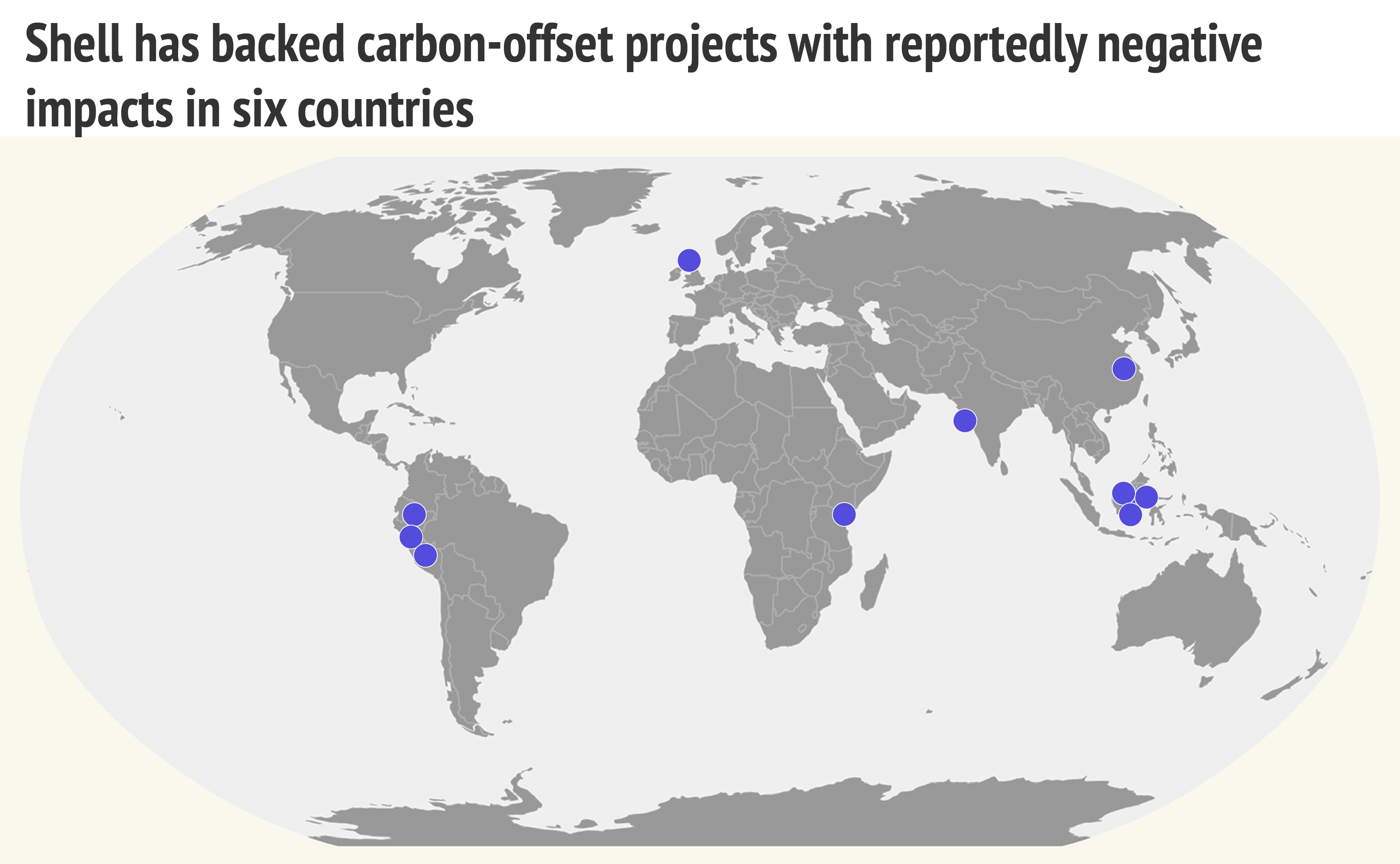

The analysis finds that UK fossil-fuel firm Shell was the business that was most mentioned in media reporting on the impacts of carbon-offset projects over the past five years.

Shell was mentioned in stories examining the impacts of carbon-offset projects in China, Indonesia, the Peruvian Amazon, Kenya, India and Scotland, the investigation shows.

In August, Bloomberg reported that Shell has abandoned its plans to invest heavily in carbon offsets by 2030.

Geographic spread of carbon-offset projects with reported negative impacts that mention Shell. Credit: Carbon Brief.

Geographic spread of carbon-offset projects with reported negative impacts that mention Shell. Credit: Carbon Brief.Other companies mentioned in reports into the impacts of carbon-offsetting over the past five years include French oil giant TotalEnergies, US fossil fuel company Chevron, British oil company BP, Meta, Netflix, Gucci, Volkswagen, Siemens, Disney, Microsoft, L’Oreal, Nestle and Barclays.

Offsetting overestimated

Some 26 out of the 61 reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects overstating their ability to reduce emissions.

Understanding the ways in which carbon-offset projects can overestimate their ability to cut emissions is important.

This is because, by design, carbon offsets do not lead to a net reduction in emissions entering the atmosphere – but rather aim to allow an entity to “cancel out” their pollution by paying for another entity to pollute less. If the entity paid to pollute less has overestimated its ability to do so, it will lead to a net increase in emissions, exacerbating climate change.

Sometimes, carbon-offset projects overstate their ability to reduce emissions through error.

In August of this year, Oregon Public Radio reported on how a fire in 2021 killed vast quantities of trees at the Green Diamond forest carbon-offset project in southern Oregon.

The Bootleg Fire is seen smoldering in southern Oregon, 17 July 2021. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

The Bootleg Fire is seen smoldering in southern Oregon, 17 July 2021. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.According to the report, the trees that burnt down stored 3.3m tonnes of CO2, “equivalent to the greenhouse gases produced in a year by more than 700,000 cars driving 11,500 miles”.

This unexpected loss of CO2 would not have been fully accounted for when the project sold credits to polluting companies looking to offset their emissions.

Sign-up to Carbon Brief’s award-winning newsletters here

However, in many of the reports studied by Carbon Brief, companies and carbon-offset project developers appeared to use specific tactics to overstate their ability to reduce emissions.

In March, Climate Home News reported that a rice farming carbon-offset project spearheaded by Shell “implemented a series of accounting tricks that would help them avoid stricter controls” in order to overstate its ability to reduce emissions. A Shell spokesperson told Climate Home News the company is conducting its own internal review.

In January, Dutch journalism publication Follow the Money released a detailed investigation into how a Swiss carbon-offsetting company allegedly overstated the offsetting potential of its flagship forest protection scheme in Zimbabwe, leading to a detectable increase in emissions. (In May, Zimbabwe announced tough new rules to crack down on “greenwashing” from foreign carbon-offsetting projects, although these were softened in August.)

And, in 2021, the Los Angeles Times reported that a forest carbon-offset project in California allegedly pushed on with selling credits to polluters even after many of its trees were burnt down in a wildfire, rendering them useless for absorbing CO2.

Indigenous rights in peril

A total 44 out of the 61 reports examined by Carbon Brief found evidence of carbon-offset projects causing harm to Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Indigenous peoples represent 6% of the global population, but act as stewards for more than 40% of Earth’s remaining intact ecosystems. Nearly half of the undamaged parts of the Amazon rainforest are in Indigenous-held lands.

Many of the carbon-offset projects around today involve developers moving in to protect large areas of intact forest, claiming that this will stop trees in these areas from being cut down – thus, reducing emissions.

However, despite the well-established role that Indigenous peoples have played in protecting ecosystems for centuries, a vast number of carbon-offsetting projects do not consult local communities or – worse – violate their rights to their land and cause them harm.

Reports examined by Carbon Brief found that Indigenous peoples have been forcibly removed from their land because of carbon-offsetting in the Republic of the Congo, DRC, Kenya, Malaysia and Indonesia, as well as the Brazilian, Colombian and Peruvian Amazon.

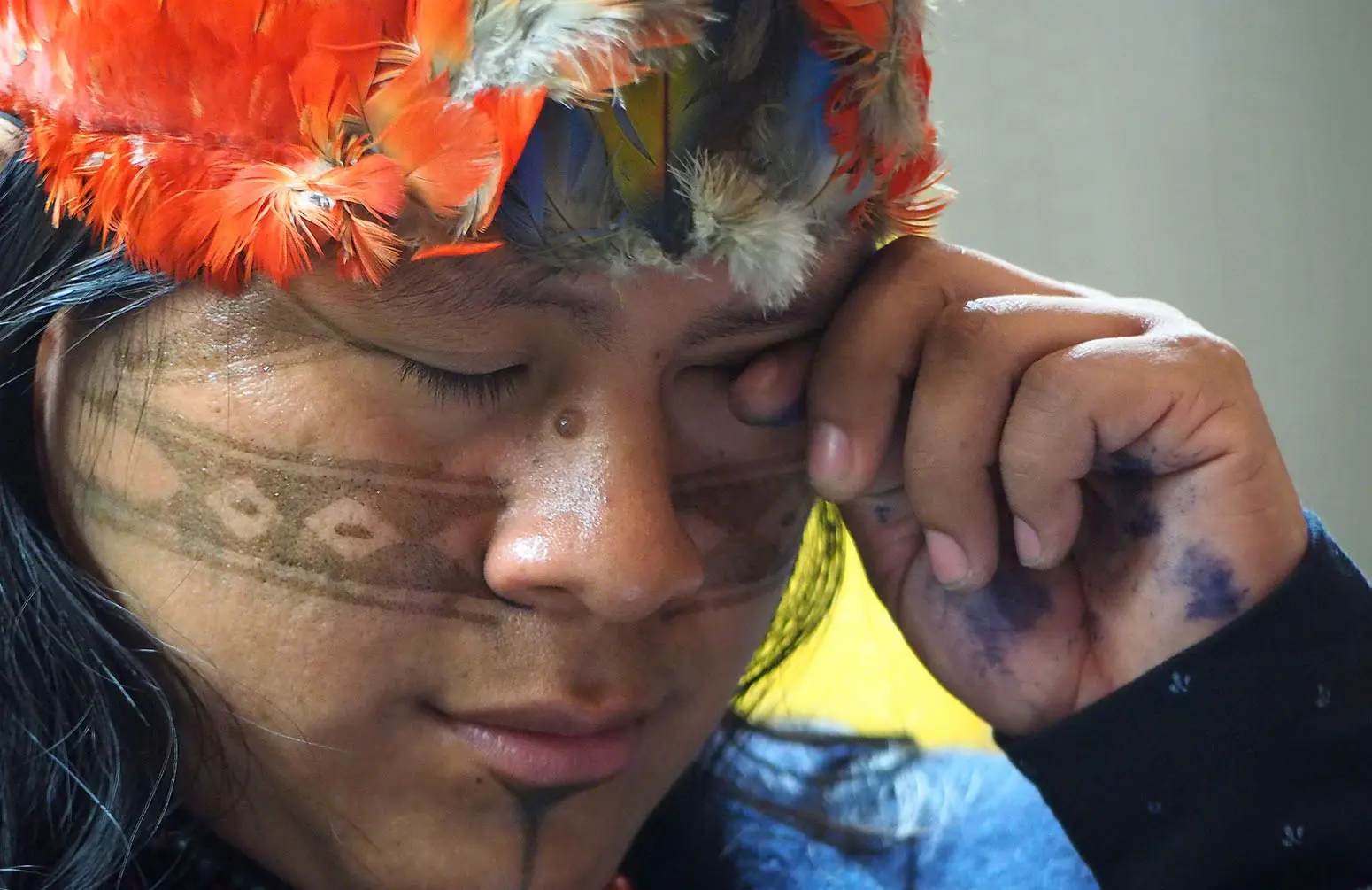

The Associated Press has produced numerous detailed reports on how the establishment of the Cordillera Azul National Park, a stretch of the Peruvian Amazon in the foothills of the Andes run by a non-profit organisation called CIMA, has allegedly had devastating consequences for the Indigenous Kichwa tribe.

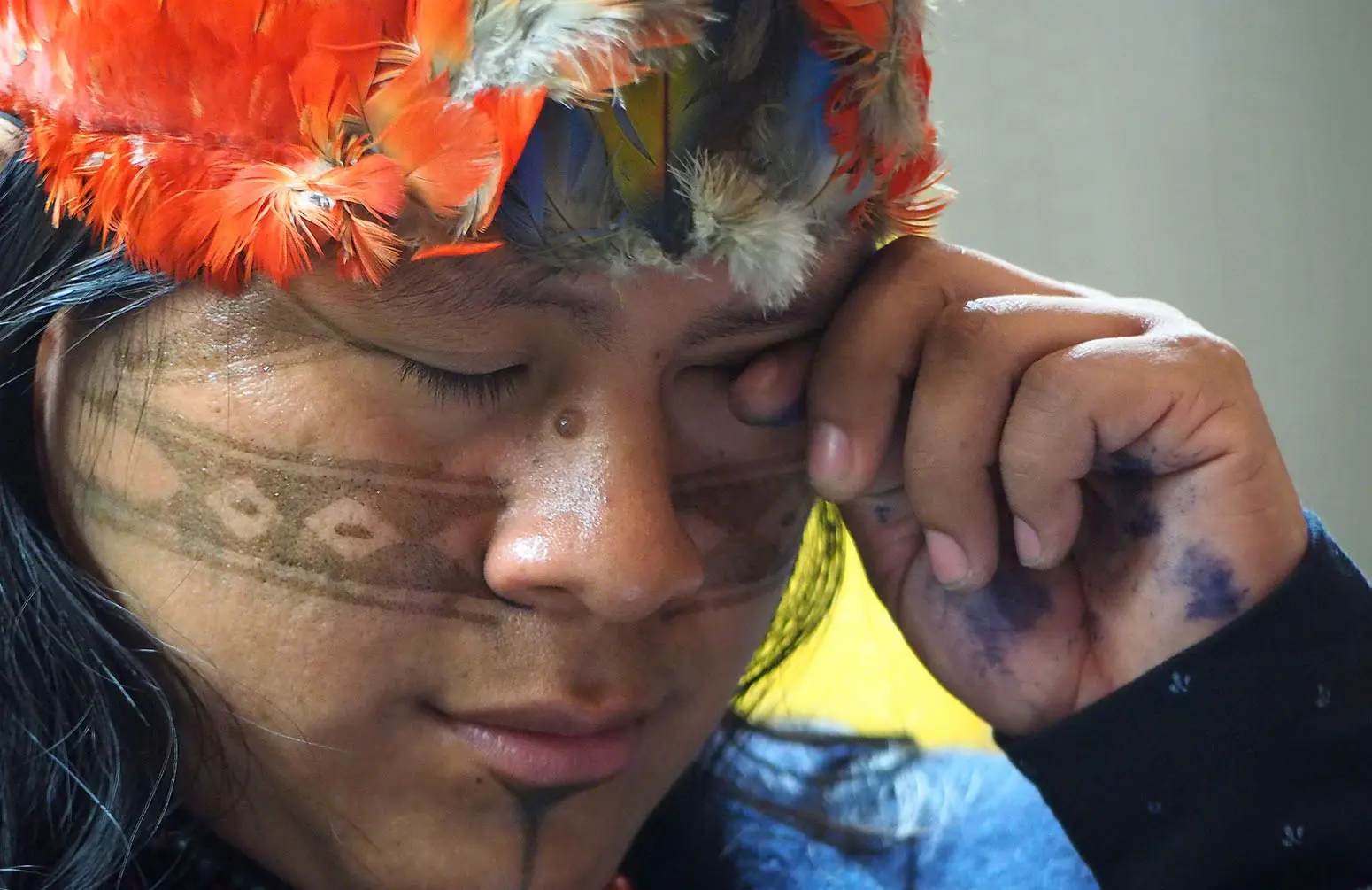

A representative from the Ecuadorian Kichwa indigenous group at the 5th Amazon Summit of Indigenous Peoples in Lima, Peru on 5th September 2022. Credit: Fotoholica Press Agency / Alamy Stock Photo.

A representative from the Ecuadorian Kichwa indigenous group at the 5th Amazon Summit of Indigenous Peoples in Lima, Peru on 5th September 2022. Credit: Fotoholica Press Agency / Alamy Stock Photo.One tribe member told the Associated Press that, when the park was first established in 2008, his traditional hunting gear was seized by armed guards from CIMA, who told him he can no longer use his ancestral land to gather food. The executive director of CIMA has denied any wrongdoing and told AP it followed national and international human rights law when establishing the park.

The project has sold carbon credits to Shell and TotalEnergies. Both companies told AP that they had carried out assessments to ensure the project benefitted local communities.

(A separate story from the Associated Press alleged that tree loss from the forest has more than doubled since the park was established, according to satellite data.)

Elsewhere in the Amazon, Mongabay in 2022 reported that a Brazilian palm oil company, which sells carbon offsets as part of its operations, had allegedly planted crops on top of the graves of Indigenous Quilombola people in the Brazilian Amazon. The company denies the allegations.

In Africa, Unearthed in 2022 reported that a tree-planting project to offset carbon for TotalEnergies had allegedly forced Indigenous families off of their farmland in the Batéké plateaux of the Republic of the Congo. TotalEnergies told Unearthed that work was underway to “establish a complete picture” of the people who had been affected by the project, and to offer them “appropriate remediation” for “negative impacts”.

In Asia, Al Jazeera published an investigation in 2022 alleging that state officials in Borneo agreed to a “secret deal” to sell off 2m hectares of land for carbon-offsetting, without consulting or informing the Indigenous peoples that lived there. State officials declined to comment on the allegations.

Update: This article was updated on 3 October to add additional carbon-offset projects to the analysis and interactive map.

Are you a journalist who has published an original story or investigation into a carbon-offset project? Please contact [email protected] to get it added to the database.