Carbon offsets have made headlines in recent years – often for the wrong reasons.

From investigations into “phantom credits” and “crypto” offset schemes through to late-night comedians running lengthy segments, journalists and researchers have revealed a range of issues that can arise through attempts to “cancel out” emissions.

But the chequered history of carbon offsets – and the ideas, experiments and policies that informed them – is much longer, spanning more than six decades.

This article is part of a week-long special series on carbon offsets.

Emissions-offsetting took root in US environmental law in the 1970s, particularly amendments to the Clean Air Act. Early experiments with trading offsets of lead, sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxide in the US laid the groundwork for market-based environmental regulation worldwide.

Such mechanisms found support from a chorus of voices, including fossil-fuel companies and conservative politicians from the UK to Australia, who favoured “efficiency” and markets over “command-and-control” environmental regulation.

Many large NGOs, such as the Environmental Defense Fund and Nature Conservancy, also argued for emissions trading over a carbon tax, even partnering with corporations to reduce their emissions.

Below, Carbon Brief’s timeline of carbon-offsetting traces the origins, ideas, arguments, milestones and controversies, from the 1960s through to today.

Offset origins

According to Dr Mark Trexler, who the World Resources Institute hired to oversee the first land-based carbon-offset scheme in 1988, the first batch of offsets projects was “purely a philanthropic exercise”.

He tells Carbon Brief they were designed more as a way of “getting companies and electric utilities to think about carbon dioxide (CO2) for the first time, to make some commitments, even if they were based on using offsets”. Trexler adds:

“No one ever thought that carbon offsets were going to save the world. That just wasn’t the way we were thinking about this. We were thinking: this is an interim measure until public policy gets going. It was a way of getting the conversation started. No one then thought that we would be doing offsets 35 years later.”

By the time the negotiations began around the Kyoto Protocol – the first UN agreement for developed countries to cut emissions – carbon offsets were “critical to [its] politics”, Trexler says, especially for getting buy-in from the US. Eventually, the US signed but did not ratify the protocol.

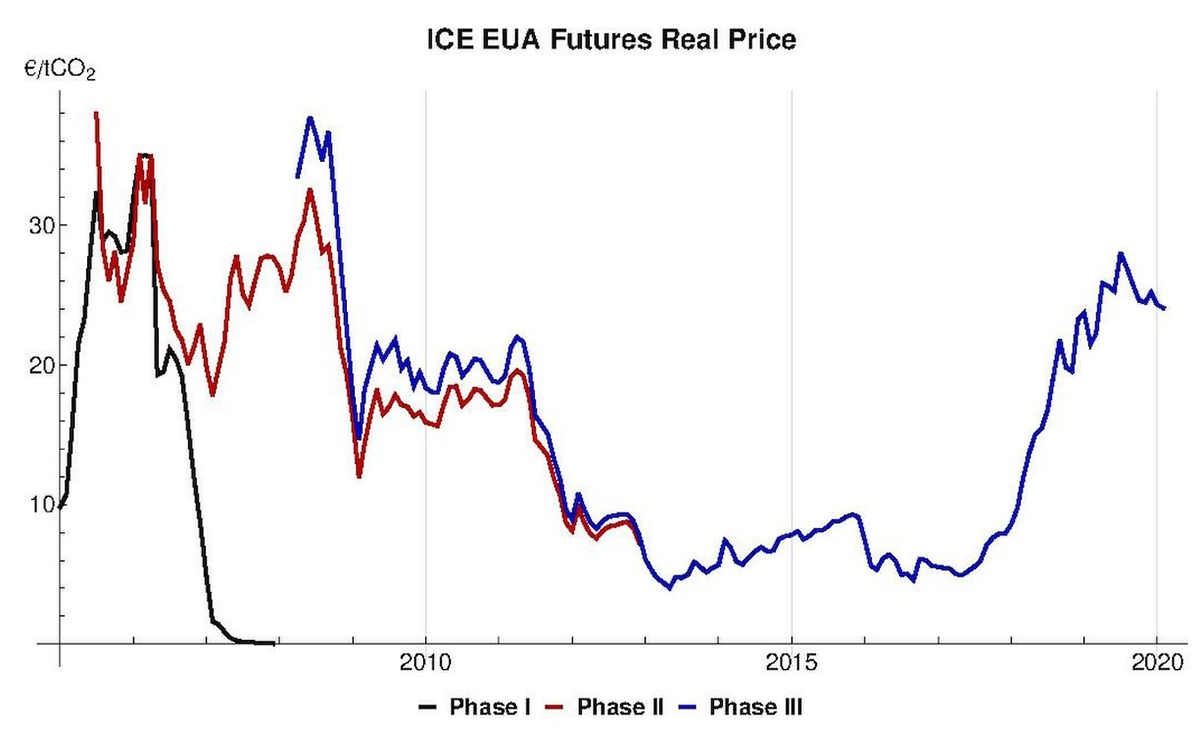

To meet their binding Kyoto emissions targets, other countries and states began experimenting with emissions trading schemes (ETSs) and carbon offsets. Among them were systems in the UK, Australia’s New South Wales, the Chicago Climate Exchange and, most notably, the EU ETS in 2005.

Meanwhile, increased scrutiny of offsets raised concerns in terms of whether offsets were actually resulting in real, verifiable emissions reductions.

However, even after Kyoto carbon markets unravelled in 2012, carbon offsets took off in the largely unregulated voluntary market, with carbon markets making their way into Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

To Trexler and other observers who “have been debating exactly the same topics in the same way for 20 years”, he says it seems that policymakers “haven’t learned the lessons” of the collapse of Kyoto markets.

The timeline below charts where progress has – or has not – been made over this period.

1960: Ronald H Coase publishes his seminal paper, "The Problem of Social Cost", which assigns property rights to pollution and argues that "arbitrage" between actors in a market with low transaction costs can result in efficient environmental solutions. Thirty years later, Coase rued that his work had been widely misunderstood, stating that “its influence on economic analysis has been less beneficial than I had hoped”.

1975: Facing backlash from industry and economists for its “command and control” clean-air regulations during oil-price shocks, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) investigates the option of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions offsets for oil, gas and steel industries, in response to many states being unable to meet the deadline for national air quality standards. It introduces an emissions trading system in 1977 that allows emissions from new sources to be offset by reductions from existing sources and later allowed for states to bank “excess” emissions reductions.

The amendments, according to EPA administrator Douglas M Costle, “will permit expanded use of coal while maintaining protection of the public health…and provide an acceptable schedule for continued future reduction in emissions from automobiles”.

1977: Physicist Freeman Dyson publishes, "Can We Control the Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere" in the journal Energy, suggesting “it should be possible in the case of a world-wide emergency” to plant enough trees and fast-growing plants to halt annual increase in emissions. He suggests this as a stopgap and not a permanent solution. (Dyson later became notorious for falsely claiming that human-caused global warming was, “on the whole, good”.)

1982-1988: US EPA rolls out lead credits. These trading and banking programmes aim to ease the transition for refineries as part of its leaded gasoline phasedown that began in 1973, even though the oil and automotive industry knew of lead’s toxicity half a century earlier. If a refiner produces gasoline with a lower total lead content than is allowed, it can earn lead credits that it is then allowed to sell. Lead credits are discontinued in 1988 and the US lead phaseout ends in 1996.

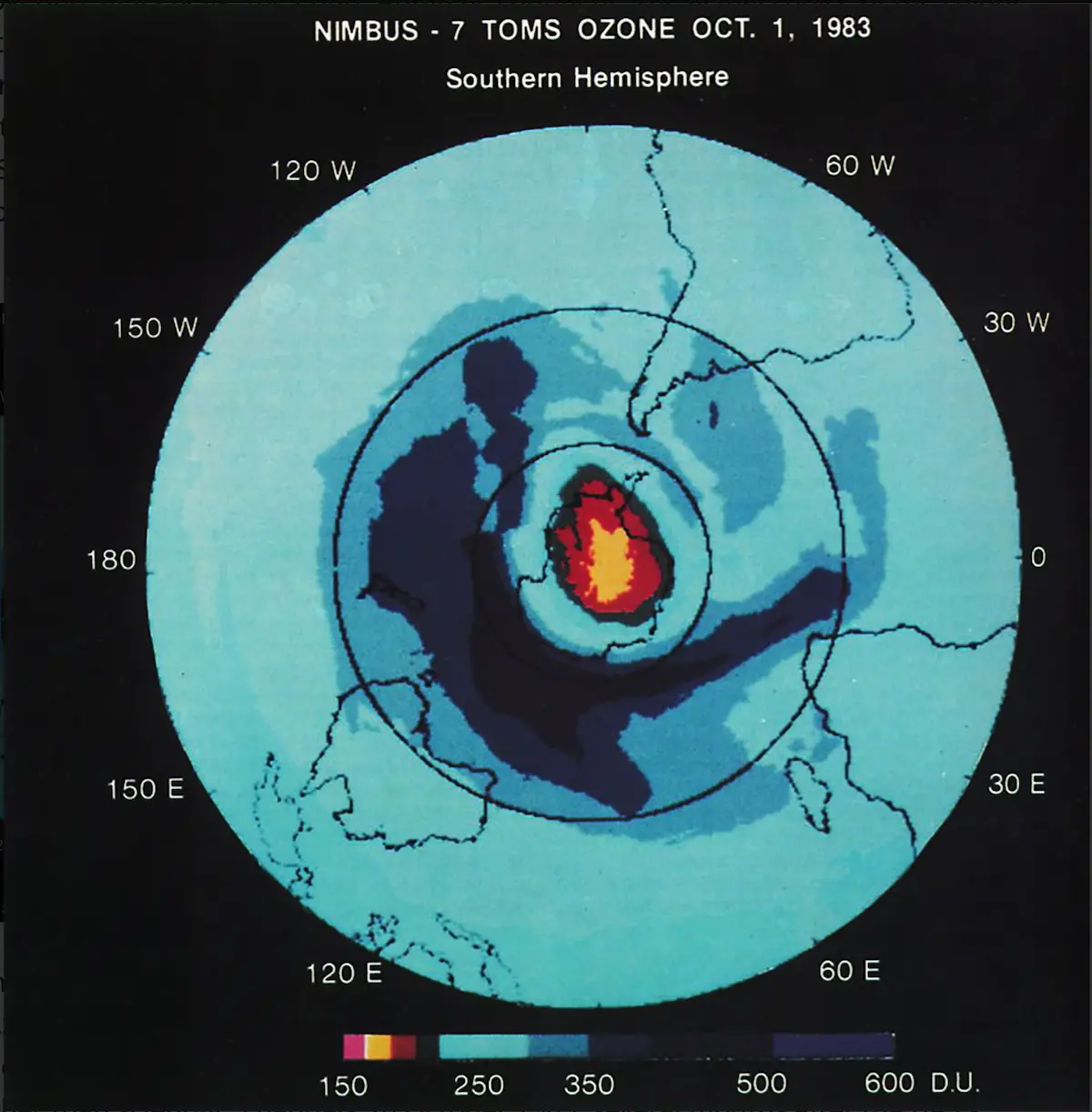

1987: The Montreal Protocol allows for limited emissions trading. The US, Europe, Canada, New Zealand and Singapore set up markets in tradeable permits and production quotas for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting substances.

1988: Applied Energy Services approaches World Resources Institute (WRI) for advice on how to mitigate the climate impacts of its coal plants. WRI recommends that AES should fund an agroforestry project to plant 52m trees, slow local deforestation in Guatemala and offset the emissions of its first coal plant in Thames, Connecticut. This is the first-ever land-based carbon-offset project.

1988: Economist Robert Stavins launches Project 88 with two US senators to advocate for emissions-trading and other market-based mechanisms to environmental problems, including climate change. The influential political advocacy project starts as a series of meetings and a report. It advances policies that “deliver improved environmental quality at reasonable cost and which are consistent with American traditions favouring voluntarism over government coercion”.

1989: David Pearce, Anil Markandya and Edward Barbier publish a report called "Blue for a Green Economy". Prepared for the UK’s Department of the Environment (DoE), it suggests how different forms of pollution can be costed and how governments can construct taxation systems and market instruments to fund the cleanup of environmental damage. The report serves as a launchpad for an influential white paper that is considered the Conservative party’s first serious engagement with a green agenda.

1990: Spurred by the work of Project 88, the US EPA under the Bush administration legislates amendments to its Clean Air Act that allow for emissions-trading of sulphur dioxide (SO2). Implemented in phases, it places a national cap on emissions and allocates “allowances” to industries to emit (in tonnes of SO2), based on their actual fuel use between 1985-87. The “successful” SO2 market becomes the basis for the US bid for the inclusion of emissions-trading in the Kyoto Protocol.

1993: In an article titled, “Greenhouse gas emission offsets: a global warming insurance policy”, Sheryl Sturges of US utility and power company AES sums up the company’s foray into forest offsets by suggesting that CO2 emission offsets could be “one way to preserve coal and gas as fuel options while mitigating any adverse global climate change effects they may have”.

1995: In Berlin, the UNFCCC’s first Conference of Parties (COP1) launches a pilot phase of “activities implemented jointly” (AIJ), allowing countries to voluntarily implement reduction or removal projects in other countries, but without accruing credits. Avoided deforestation is hotly discussed, but is, ultimately, left off the table for financing. This drives projects to the voluntary market.

1997: The Kyoto Protocol introduces three different “flexible mechanisms” for nations to engage in carbon-trading. These are: emissions-trading between countries with binding targets; the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), where developed countries can buy credits from projects in developing countries; and Joint Implementation (JI), where developed countries can get credits from projects carried out in other developed countries.

1997: Environmental Defense Fund partners with oil major BP to help operate its in-house emissions trading scheme. The next year, BP pledges to reduce its emissions 10% below 1990 levels by 2010, a move EDF calls a “magnificent example of a corporation acting responsibly” and a commitment “going beyond what the Kyoto Protocol would require”.

1999: A group of companies and business associations – including Transalta, BP, Rio Tinto, Mitsubishi, KPMG, Norsk Hydro and the Emissions Trading Association of Australia – form the Internatinal Emissions Trading Association (IETA), the first “purely business” group dedicated to pricing and trading greenhouse gas reductions. One year later, the group publishes the first voluntary carbon-market standards, to help companies looking to voluntarily offset their emissions and demonstrate corporate responsibility.

2002: To meet the EU’s Kyoto commitments and national targets, the UK becomes the first government to introduce an economy-wide emissions trading scheme with a five-year lifespan. Individual firms are required to commit to a specific level of emissions cuts in 2006, in exchange for a subsidy per tonne of emissions below that level.

2003: EU member states agree to an ambitious EU ETS to help achieve the EU-wide emissions reduction target under the Kyoto Protocol, “with the least possible diminution of economic development and employment”. In its early phases, the scheme puts a cap only on the EU’s CO2 emissions from fixed industrial installations, leaving out other greenhouse gases and sectors. These early phases lacked reliable baseline data, encouraging emitters to inflate their emissions and profit from CO2 allowances. Carbon prices, however, remained lower than levels believed to effectively reduce emissions.

2005: The discussion on reducing emissions from deforestation (REDD) begins at COP11 in Montreal, under a proposal put forward by Papua New Guinea and Costa Rica.

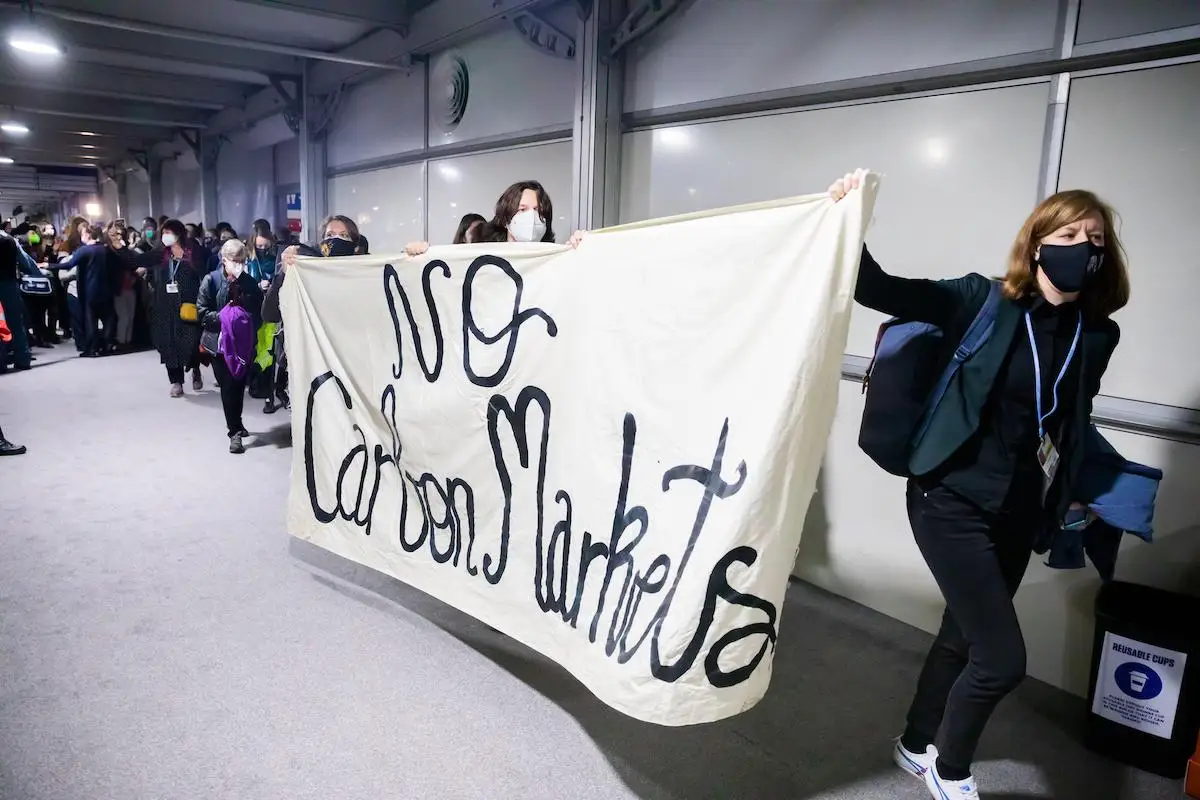

2007: In the first-ever widely publicised protests against carbon-offsetting, Plane Stupid campaigners hand over a parcel of herring – to symbolise a red herring – to senior staff at the offset company Climate Care in Oxford, UK. Protestor liken offsetting to “being a member of the RSPCA then going home and kicking a dog”. The incident marks one of the first specific protests against offsetting.

2008: The value of global carbon markets soar 84% to $118bn amid a global financial crisis, with the EU’s allowances accounting for 80% and CDM credits 13% of the value. The "carbon rush" in Kyoto’s first commitment period means that offset markets begin to see more scrutiny.

2012: Markets go into “carbon panic” mode as CDM credit prices drop to less than $3 per tonne of CO2 in response to oversupply. This is largely due to the EU stopping the purchase and use of indsutrial gas credits and Japan deciding against buying credits, in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster. Trade in CDM credits collapses just five years after the mechanism’s launch, while developed countries face criticism for “hot-air laundering” credits generated in other developed countries.

2015: The Paris Agreement, reached by nations at the COP21 climate summit, contains Article 6, which covers “voluntary cooperation” to help countries meet their climate goals. This includes two “market-based” approaches that set the stage for two new avenues by which all countries can trade offsets with each other.

2020: After years of pressure, Australia’s prime minister Scott Morrison agrees to abandon a long-standing plan to use “carryover” credits from the Kyoto Protocol to meet the country’s Paris Agreement targets.

2021: A year after the Paris Agreement regime officially begins, negotiations over its “rulebook” come to a close in Glasgow. Regulations around Article 6 carbon markets that could “make or break” the deal had been a key sticking point. Countries close off “double-counting”, which would allow more than one entity to count offsets towards their emissions reductions, but agree to controversial carryover Kyoto credits generated since 2013. They also signal an independent grievance mechanism for disputes around carbon-offsetting projects, a key ask from Indigenous groups.

2022: A report by the UN high-level group on the net-zero commitments of non-state actors calls for “zero tolerance for net-zero greenwashing”. It warns companies against buying cheap, low-integrity credits instead of making immediate emissions cuts, while asking the voluntary carbon market to respect human rights and consult affected Indigenous and local communities “responsible for the stewardship of…ecosystems used for offsetting projects”.

This article is part of a week-long special series on carbon offsets.