China is currently the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, as well as the largest manufacturer of low-carbon technologies.

The country’s climate and energy policies can greatly affect the pace of progress – both domestically and internationally – towards the Paris Agreement’s global goal of avoiding dangerous climate change.

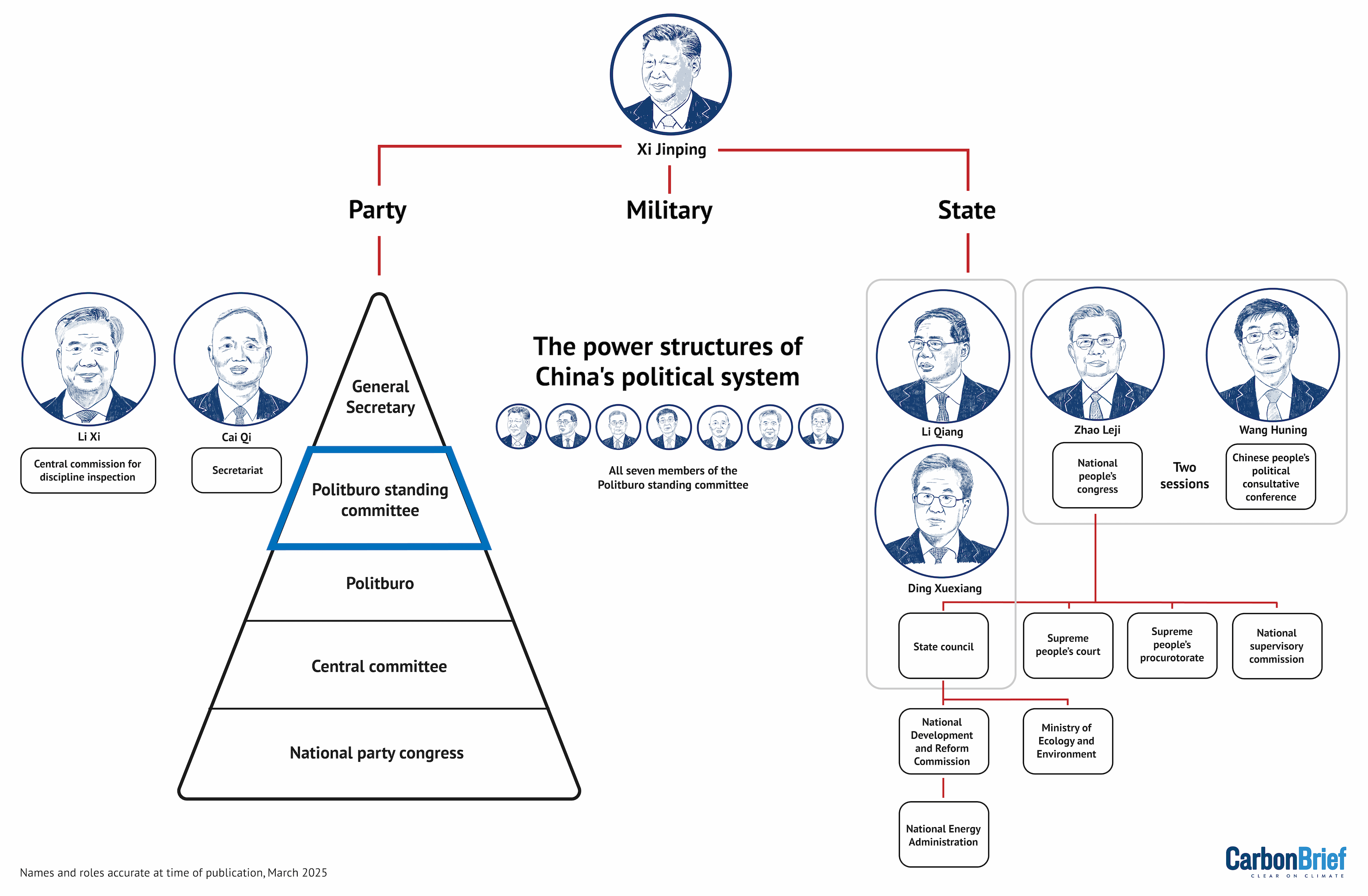

However, the policies issued by various Chinese authorities – which function under a complex political system made up of a labyrinth of committees, conferences and other bodies – are often described using a wide variety of opaque jargon and acronyms.

Newly created terms often need clarification and interpretation to form a full understanding of what they mean in practical terms.

Below, Carbon Brief provides a detailed guide to the jargon – from the frequently used to the obscure – appearing in China’s climate-related lexicon.

Explanations of the Chinese political system – and the functions of departments within the system – are also included within the glossary.

All the explanations below are based on official definitions, or expert interpretations of official websites and documents.

Climate policy

‘Dual-carbon’ goals 双碳目标

“Dual-carbon” goals, or the “2030/2060 goals”, refer to China’s two climate goals announced by President Xi Jinping at the 75th session of the UN General Assembly in September 2020. Xi announced that China would reach its carbon emissions peak “before 2030” and then achieve “carbon neutrality by 2060”. In July 2021, China’s climate envoy announced that the country’s 2030 target refers to the peaking of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, while its “carbon-neutrality” goal covers “all greenhouse gases” (GHG). Since Xi’s pledge, all China’s climate policies are fundamentally based on these targets.

‘1+N’ policy framework ‘1+N’政策体系

“1+N” is a systematic set of directives being formulated by China to help achieve its “dual-carbon” goals. According to China’s former climate envoy Xie Zhenhua, the “1” refers to the central “guiding opinions” on the “dual-carbon” goals, while the “N” stands for the “action plan” for the 2030 peak emissions goal, as well as “policy measures and actions” for “key sectors and industries”. On 24 October 2021, China released the “1”, officially titled: “Working guidance for carbon dioxide peaking and carbon neutrality in full and faithful implementation of the new development philosophy.” Two days later, it published part of the “N” – the “action plan for carbon-dioxide peaking before 2030”.

Energy intensity 能耗强度

Energy intensity is energy consumption per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) or economic output. China has been issuing an energy-intensity target annually since the 11th “five-year plan” (2006-2010). It has fulfilled all of these targets – GDP growth rate surpassed the growth of energy consumption – except in 2023. In 2024, the Chinese government announced that clean energy would be excluded from energy intensity, setting the annual reduction target for the improvement in the fossil fuel energy intensity of the economy at “about 2.5%”. An analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst of Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, says the redefined target focused on fossil fuels is “significantly easier to meet” and the 2.5% goal means CO2 emissions would be allowed to increase by “up to 2.4%”, if annual GDP growth – around 5% – is “on target”.

Carbon intensity 碳强度

Carbon intensity means CO2 emissions per unit of GDP. China’s national average carbon intensity was 0.4kg CO2 per US dollar in 2020, according to data from the World Bank, although there is wide variation between the most and least carbon-intensive provinces. China’s carbon intensity “has been steadily improving” over the years, according to thinktank Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, but it “remains high in comparison with other major economies”, including the US (0.2), Japan (0.19) and the EU (0.13). Beijing’s overall target for the 14th “five-year plan” (2021-2025) is to cut carbon intensity by 18% – a target that has been widely expected to be “missed” – and 2024's annual goal is to “decrease by 3.9%”.

‘Dual control of energy’ 能耗双控

In 2016, China established a set of targets for controlling energy intensity – energy consumption per unit of GDP – and total energy consumption, in a system known as the “dual control of energy”. Total energy consumption control covers both fossil-fuel and non-fossil energy consumption, as well as consumption for raw materials. The targets set by the dual-control system, however, do not cover total CO2 emissions. Official news agency Xinhua has said the system does not “completely match” the “dual-carbon” goal that was proposed four years later – considering its control over renewable energy – and, therefore, was replaced by the “dual control of carbon” system in 2024. (Read more about “dual control” in this edition of China Briefing.)

‘Dual control of carbon’ 碳排放双控

“Dual control of carbon” is a replacement system for “dual control of energy” that shifts away from energy intensity and energy consumption. Instead, it focuses on carbon intensity and total carbon emissions. The system was established in 2024. Under this system, China will initially focus on reducing carbon intensity, with a secondary focus on total CO2 emissions. After 2030 – before which China has pledged to reach its carbon peak – a binding cap for total CO2 emissions will be set and will become the main target, while carbon intensity will be the secondary target. (Read more about the “dual-control” system in this edition of China Briefing.)

‘Campaign-style carbon reduction’ 运动式“减碳”

“Campaign-style carbon reduction” is a term that was first mentioned in a meeting of the Politburo – the Chinese Communist party’s core decision-making body – in July 2021. The meeting instructed the country to “stick to a single game nationwide, rectify campaign-style ‘carbon reduction’” and “establish [new rules] before breaking [old ones]”, while striving towards “dual-carbon” goals. Explaining the term, Prof Alex Wang, the faculty co-director of the UCLA School of Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, tells Carbon Brief that the leadership was ordering regional governments to move towards the climate goals in a “rational” and “strategic” way that takes into consideration other national priorities, such as the economy and energy supply.

‘Build before breaking’ 先立后破

In 2021, Xi used the phrase “establish [new rules] before breaking [old ones]” when talking about how the country should achieve its “dual-carbon” goals, according to the official website of the Communist party of China. He contrasted this approach with “campaign style carbon reduction”, which he said should be “corrected”. The website adds that in 2022, Xi said “we should adhere to the principle of building before breaking” in relation to the country’s energy transition. The idea is that China is aiming to expand its low-carbon energy supplies before shifting away from fossil fuels, namely “build before breaking”. This is China’s “principle” for reducing coal usage as part of the energy transition, explained Prof Bai Quan in a 2024 interview with Carbon Brief. Bai is a director of the Academy of Macroeconomic Research, a research institution under the direct supervision of the China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Other translations of the slogan have included “building the new before destroying the old”, “establishing the new before abolishing the old” and “construction of the new before destroying the old”.

‘One-size-fits-all approach’ 一刀切

The “one-size-fits-all approach” is the common English translation of a Chinese phrase which means that judging differing situations by the same yardstick can lead to a negative outcome. The term is frequently used to describe a governing style, which sees local authorities setting the same goals, issuing the same orders or using the same evaluation methods on different areas or sectors – regardless of their practical situations – in order to meet mandatory targets assigned by the central government. “One-size-fits-all approach” has been used alongside the idea of “campaign-style carbon reduction” in energy and climate policies. In one example, China’s leadership ordered some regions to “rectify” their “one-size-fits-all” approach and their “campaign-style carbon reduction” efforts, which they had implemented in a bid to hit their energy-saving objectives via “some extreme behaviours”.

Energy policy

‘New energy’ 新能源

The Chinese government does not give an official definition of “new energy”, but in a regulation document for “new energy basic construction projects”, the National Energy Administration says: “New energy refers to electricity or clean fuel that has been converted or processed from renewable resources, such as wind energy, solar energy, geothermal energy, ocean energy and biomass energy.” State broadcaster CCTV used the term “new energy” when reporting on a budget issued by the Ministry of Finance relating to how “renewable energy” was used to generate electricity in 2021. According to a book published by Tsinghua University, the term refers to the renewable energy developed and utilised using “new technologies”. The term covers solar, hydro, wind power, biomass energy and hydrogen fuel, among other energy forms. China’s National Energy Administration said in 2021 that the country was promoting “new energy” as the “main source” of electricity supply in its “new style” electric power system aimed at achieving its climate goals.

‘New-energy vehicle’ 新能源汽车

In China, “new-energy vehicles” (NEVs) refer to the automobiles that use a “new type” of power system and are driven entirely, or mainly, by a “new type” of energy, according to an official notice. It primarily includes pure electric vehicles (EVs), plug-in hybrid vehicles and fuel-cell vehicles. In October 2020, the State Council released an industry plan for “new-energy vehicles”, which runs from 2021 to 2035. The document describes the development of “new-energy vehicles” as a national strategy. It urges all regions and officials to promote the “high-quality” and “sustainable” growth of the industry. (Read Carbon Brief’s Q&A on the global “trade war” over China’s booming EV industry.)

‘Ballast stone’ 压舱石

“Ballast stone” is a political term often used in energy policy discussions to emphasise the need for stable energy supply – often termed energy security. For example, an article from the Communist party-affiliated People’s Daily that was reposted on the National Energy Administration’s official website in 2024 referred to coal as the “ballast stone” for China’s energy security. The phrase is also used more broadly. For example, as early as January 2013, President Xi described four historical political agreements with Japan as “ballast stones” for “stabilising [Sino-Japanese] bilateral relations”. The phrase has since developed to “refer to important measures or means to ensure stability”, according to Study Times, an official newspaper edited by the central school of the Chinese Communist party.

‘Dual-high’ projects 两高项目

“Dual-high” is a term used by Chinese authorities to refer to projects or industries with high energy consumption (高耗能) and high emissions (高排放). China’s State Council has said in an action plan for “carbon peak by 2030” that the “blind development” of “dual-high” projects must be “resolutely curbed”.

Xiaona 消纳

Xiaona can be translated either as “absorption quotas [of renewable energy consumption]”, or “responsibility weights [in renewable energy consumption]”. It is a Chinese term for a renewable portfolio standard (RPS), which requires energy producers and providers to supply a certain amount of electricity from renewable sources. In China, different quotas are set in different provinces. Regulators can also set industry-specific Xiaona requirements. The aluminium industry was given such quotas in 2024, with compliance linked to the use of “green electricity certificates”. (Read more about China’s 2024 RPS action plan in China Briefing.)

ETS 全国碳排放交易体系

China’s emissions trading scheme (ETS), the country’s mandatory carbon market, is the world’s largest ETS in terms of covered emissions. China has a national ETS market and several local ETS markets. The ETS currently only covers the power sector. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) issued a draft policy announcing its intention to expand the ETS to also cover steel, aluminium and cement in late 2024, although this has not been implemented as of early 2025. The expansion would raise the share of national carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions covered by the market from 40% to 60% of China’s total.

CCER 全国温室气体自愿减排交易系统

In contrast to the ETS, CCER – the China Certified Emission Reductions scheme – is a government-run mechanism for issuing carbon credits. CCER grants participants carbon credits for projects that reduce overall carbon emissions, including renewable power generation, forestry and waste-to-energy projects. Launched in 2012, it was paused in 2017 due to small volumes of trading. China relaunched CCER in 2024 and the credits can now be sold to ETS participants to help offset up to 5% of their compliance obligations. Non-ETS participants, including individuals and overseas companies, can also purchase CCER credits. CCER credits are for single use only and cannot be re-traded.

GECs 绿证

The Green Electricity Certificates (GECs), linked to the ETS, are also known as China’s “domestic renewable energy certificate scheme”. GECs were introduced in 2017 and trace the whole lifecycle of “green electricity” from production and trading through to consumption. Chinese online science media outlet 36Kr explains that GECs “equals renewable electricity” and is “an electric green consumption receipt”. GECs can be traded multiple times, providing a revenue stream to companies that use more renewable power. From August 2023, GECs expanded from just covering wind and solar energy through to “all types of renewable energy projects”, including biomass, hydropower and geothermal. (Read more about CCER and GECs on Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.)

The boundaries between GECs and CCERs were refined in September 2024, when a two-year transition period began that allowed offshore wind and solar thermal projects to choose between selling under one or the other of them, but not both. Onshore wind and solar photovoltaic schemes are not included in the CCER market, according to the policy jointly issued by National Energy Administration (NEA) and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE).

General policy

‘Five-year plan’ 五年规划

A “five-year plan” is a comprehensive policy blueprint released every five years to guide China’s overall economic and social development. The system was first used by the Soviet Union in 1928 and later adopted by the Communist party of China to set out economic quotas for the newly founded People’s Republic of China. Chairman Mao Zedong led the drafting of the country’s first “five-year plan”, which ran from 1953 to 1957. Since then, China has released and implemented successive “five-year plans”, which inform all policymaking at national, sectoral, provincial and regional levels for the period they govern. The overarching plans should not be confused with province- or topic-specific “five-year plans”, which are often released later in the five-year plan period by specific government ministries or local governments.

14th ‘five-year plan’ 十四五规划

The 14th “five-year plan” is the current “five-year plan” active in China. It is shorthand for the “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035”. It was drafted by the State Council and approved in March 2021 at the annual “two sessions” – an annual gathering in Beijing of influential political figures. The policy document lists the nation’s 20 most important economic and social targets from 2021-2025 and explains the government’s long-term developmental goals, setting tasks in areas from the economy through to “ecological civilisation”. The outline provides a taste of the range of regional and sectoral plans that were published over the following year. (Read Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A in detail.)

Xi Jinping Thought 习近平思想

Xi Jinping Thought is shorthand for “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”. It is a series of key ideas and policies derived from the speeches and writings of China’s president Xi Jinping. It has been described as a new ideology that “promotes the supremacy of the Communist party” in a more market-oriented China. It comprises eight “fundamental issues” and 14 “fundamental principles” that the country must follow. The belief system was enshrined into the constitution of the Communist party of China in 2017, “signifying a leap forward in the sinicisation of Marxism”, according to state news agency Xinhua. The “thought” in 2024 included the importance of “green” development.

Xi Jinping Thought on ‘ecological civilisation’ 习近平生态文明思想

Xi Jinping Thought on “ecological civilisation” is a “significant part” of Xi Jinping Thought and the “scientific guideline” for building what Xi calls a “beautiful China” with an “ecological civilisation”, according to state-run newspaper China Daily. The concept is often cited as a foundation for new policies focused on environmental protection and “green” development. “Ecological civilisation” refers to a civilisation form in which human beings and nature “coexist harmoniously” – a notion highly promoted by Xi. He famously said: “Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets.” (Xi’s “two-mountains” theory.) The metaphor represents Xi's order to combine “ecological civilisation” into all aspects of the nation’s development, as explained by the People's Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist party. (For more, see Carbon Brief’s “Analysis: Nine key moments that changed China’s mind about climate change”.)

‘Beautiful China’ 美丽中国

The concept of “beautiful China” was first brought up at the 18th National Party Congress in late 2012 and has since been championed by Xi. It calls for “respecting, adapting to and protecting nature”. It “shows that environmental objectives are now becoming a core requirement of all social and economic development,” says the state-funded China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development. A major policy document for 2024, which outlined the key aspects of “beautiful China”, set a wide range of targets including “green and low-carbon development will be further promoted by 2027” and “'new-energy vehicles' will account for 45% of new cars by 2027”.

‘Ecological civilisation’ 生态文明

“Ecological civilisation” is a social developmental goal enshrined in the constitution of the Communist party of China. The term refers to a form of civilisation in which human beings and nature “coexist harmoniously”. The concept was first endorsed by president Xi Jinping's predecessor, president Hu Jintao, in 2007, to help China develop sustainable and ecological industrial structures, growth patterns and consumption modes. President Xi bolstered the idea after becoming the Communist party leader in 2012. The leader has described the construction of “ecological civilisation” as building a “beautiful China”.

‘Two mountains’ theory 两山论

The “two mountains” theory, according to the State Council, was proposed by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2005 during a trip to a village in Zhejiang province. (News website Hong Kong Free Press claims that the phrase had appeared in newspapers before it was popularised by Xi.) The full slogan is “clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as gold and silver mountains”, meaning that while economic development is a priority, the environment cannot be sacrificed for the sake of growth. It is also translated as “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets”. State news agency Xinhua says the theory “allows the world to understand ‘beautiful China’” and calls it a display of “Chinese knowledge and a Chinese solution” for global environmental problems. (For more, see Carbon Brief’s “Analysis: Nine key moments that changed China’s mind about climate change”.)

Economic policy

‘New three’ 新三样

China’s “new three” products – photovoltaic solar panels, lithium-ion batteries and “new-energy vehicles” – have been labelled as the “new growth points for exports” since early 2023 by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. This followed what the ministry described as the “extremely difficult year” of 2022 for China’s foreign trade. The three categories are also driving the growing economic performance of clean-energy technologies, which comprised more than 10% of China’s GDP in 2024, according to analysis published by Carbon Brief. In 2023, the total exports of the “new three” reached $148bn, up 30% year-on-year. The phrase is an update of the term “old three”, which refers to household appliances, furniture and clothing – the drivers behind China’s earlier economic boom. The tech-heavy “new three” are representative of China being a global “pioneer” in technological development, rather than a “successor” of western technology, reported state broadcaster CCTV. President Xi has also described them as “creating huge green market opportunities” at the 2023 APAC meeting.

New quality productive forces 新质生产力

New quality productive forces (NQPF) is a term referring to innovation-led development that creates a “break with traditional economic growth models and development pathways”, resulting in a “high level of technology, efficiency and quality”, plus an “in-depth transformation and upgrading of industry”. The term first appeared in official rhetoric in September 2023 and was reiterated in 2024 at the Communist party’s Third Plenum, an important five-yearly meeting traditionally associated with major economic reforms. President Xi has called “green development” – namely, the transition of China’s economic system to limit its impact on the climate and encourage development of low-carbon technologies – an important element of NQPF. In comments made in January 2024, Xi said that “new quality productivity itself is green productivity” (新质生产力本身就是绿色生产力). (See Carbon Brief’s Q&A on what China’s push for “new quality productive forces” means for climate action.)

The Belt and Road Initiative 一带一路

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s global infrastructure development strategy. It aims to link China with more than 60 countries in Asia, Europe and Africa by building railways, roads and maritime trading routes. (See the Guardian's map.) The scheme comprises the “silk road economic belt” and the “21st-century maritime silk road”. From 2013-2023, the trade via BRI reached more than $19tn, with China investing $240bn in BRI countries, according to state news agency Xinhua. In 2023, energy projects made up 36% of BRI investment, while transport projects accounted for 28%, according to the Green Finance and Development Center at Fudan University in Shanghai. (See Carbon Brief’s interview with experts on how the next decade of China’s BRI will impact climate action.)

‘Circular economy’ 循环经济

The concept of a “circular economy” appeared in China’s 14th “five-year plan” in 2021. It is an economic model that “stresses the importance of maximising resource use and the lifecycle of products”, according to China Briefing. It is also “in contrast to the ‘linear economy,’ where resources are extracted to make single-use products or products that are disposed after use”. The official document says the circular economy is of “great significance to promote the realisation of carbon peak and carbon neutrality and promote the construction of 'ecological civilisation'”.

‘Two new’ 两新

China’s “two new” policy refers to “large-scale equipment renewals” and “trade-ins of consumer goods” for energy saving, economic stimulus and carbon reduction. The policy was issued by the State Council in 2024. It has four aspects: “implementing equipment updates”; “trade-in of consumer goods”; “recycling”; and “improving standards”. Recycling, in particular, is to serve China’s “circular economy”. In line with the policy, China established a state-owned enterprise, China Resources Recycling Group, to recycle steel, as well as batteries and plastics, among other materials. President Xi supported the launch of the company, saying the establishment is “an important decision…to perfect an economy that facilitates green, low-carbon, and circular development, and advance the building of a 'beautiful China' on all fronts”. (See Carbon Brief’s Q&A on how China’s “two new” policy aims to help cut emissions.)

State-owned enterprises 国有企业

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are organisations set up to carry out commercial activities on behalf of the government. They play a “crucial role” in China’s economy, particularly in key sectors such as energy. More than half of China’s electricity has been generated by nine SOEs since at least 2010. According to the World Bank, SOEs accounted for 23-28% of China’s GDP in 2017. Thinktank Chatham House says the link between SOEs and the Chinese government is “not…straightforward”. Despite “Beijing’s central institutions” setting the parameters for the economic engagements of SOEs, they “regularly sidestep government institutions”, it says. The three Chinese national oil companies, for example, have “consistently blocked efforts to form a ministry of energy”, with each of them having “strong political backing from individual members of the [Politburo] Standing Committee”, according to the thinktank Center on Global Energy Policy at New York’s Columbia University.

Political institutions

China’s political hierarchy

China is ruled by the Communist party, which also controls the state and the military. The ruling party’s head, the “general secretary”, is invariably endorsed as the president of the country by the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s equivalent of a parliament.

The majority of NPC delegates are from the Communist party, making it a “rubberstamp parliament”. The NPC and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, hold China’s most important annual political meetings, known as the “two sessions”.

Since 2013, Xi Jinping has been the head of the Communist party and the head of state. He also assumed the highest commanding power of the military in 2016, giving him broader powers than his predecessors.

Communist party leaders, collectively elected at the National Party Congress of the Communist party, are commonly seen as being in charge of the state. For example, the Communist party’s second most powerful leader, Li Qiang, is the head of the State Council, China’s central government.

Only a limited number of non-Communist party members have ever taken high positions in the state. One example is Huang Runqiu, who has been the minister of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment since 2020. Huang is a member of the Jiusan Society – a minor political grouping – and as of early 2025 was the only minister that is not from the Communist party.

China’s political hierarchy is shown in the graphic below. The most powerful group is the Politburo Standing Committee, highlighted in blue, which has seven members during its current term (2022-2027).

National People’s Congress 全国人民代表大会

The National People’s Congress (NPC) is, on paper, China’s highest organ of state power, but is more widely perceived as what BBC News describes as a “rubberstamp parliament”. Its functions include amending the constitution, enacting basic laws, electing key leadership members and determining major state issues. Its members or delegates, formally known as deputies, are elected from each of China’s provincial-level regions. The delegates are elected for a term of five years and usually meet once a year. The current NPC, or 14th NPC, has nearly 3,000 active deputies, with more than half of them being Communist party members. In turn, these members elect a small permanent body of the NPC, known as the Standing Committee (NPCSC), which meets regularly throughout the year. The current serving NPCSC has 175 members. The NPC and the NPCSC exercise the legislative power of the state together.

Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference 中国人民政治协商会议

The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) is the formal advisory body of the National People’s Congress (NPC), the highest organ of state power in China. It does not hold any legislative power. Its main functions are to “conduct political consultation, exercise democratic oversight and participate in the discussion and the handling of state affairs”. The CPPCC’s national committee convenes every spring – usually two days before the opening of the NPC – to provide political consultation to the latter. The committee currently has more than 2,000 members who come from all walks of life. Although China is effectively a one-party state, the committee also includes members from eight other minor political parties. These are officially allowed, although their leaders are appointed by the Communist Party.

‘Two sessions’ 两会

The “two sessions” is a collective term for two major national political meetings held in China every spring – arguably the most important meetings on the political calendar. Known as “liang hui” in Mandarin, they are the plenary sessions of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. During the annual conferences, delegates collectively review and approve national economic and social development plans. A centrepiece of the “two sessions” is the premier, the head of the State Council, delivering a “report on the work of the government”, which underscores achievements from the previous year and outlines priorities for the year ahead, such as setting the GDP growth target. (See Carbon Brief’s Q&A on what China’s “two sessions” mean for climate policy in 2024 and 2025.)

The Communist party of China 中国共产党

The Communist party of China, founded in July 1921, is the ruling party of the People’s Republic of China and on track to reach 100 million members. An official Communist party document says: “The highest leading body of the party is the National Party Congress and the Central Committee it produces. The leading bodies of the party at all local levels are the local party congresses at all levels and the committees they produce.” The Communist party also holds smaller sized party congresses at local levels once every five years. They establish “Primary Party organisations”. The best known of these organisations are party cells (dang zhi bu, 党支部), which are found in enterprises, rural areas, schools, scientific research institutes, communities, etc. The party has a watchdog, known as the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, which President Xi greatly relied on during his anti-corruption campaign. The current head of the watchdog is Li Xi, the seventh most senior member of the Communist party.

National Party Congress of the Communist party of China 中国共产党全国代表大会

The National Party Congress is held every five years. Its attendees, different from the National People’s Congress, are members of the Communist party only. The National Party Congress selects the most senior leadership team of the ruling Communist party for the next five years. It also indicates the direction the country will be heading in the near future, making it the “most important date in China’s political calendar”. The latest party congress, the 20th Congress, was held in 2022 where Xi Jinping was reappointed as general secretary of the communist party for a third term.

Central Committee of the Communist party 共产党中央委员会

The Central Committee of the Communist party of China (CCCPC) is a political organ consisting of the country’s most senior officials. The committee is elected every five years by the National Party Congress (NCCPC). Together, the CCCPC and NCCPC together form the “supreme leading organ” of the Communist party of China, according to China’s official explanation of its political system. The current CCCPC comprises 205 members.

Politburo 政治局

The Politburo, or Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist party of China, is elected every five years by the Central Committee at the National Party Congress. The first Politburo – whose members included Lenin and Stalin – was created in Russia by the Bolsheviks in 1917. Nowadays, the most prominent Politburo is that of the Communist party of China. Non-profit thintank the Centre for Strategic Translation says that, “while day-to-day decision-making authority for the Communist party rests with the [Politburo] Standing Committee, Politburo members possess considerable influence over both national policy and personnel selection”. Currently, it has 24 members, including President Xi.

Politburo Standing Committee 政治局常务委员会

The Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) is the core body of the Politburo. It holds the most political power in China for the majority of the year. The PSC usually has fewer than 10 people. The 20th PSC, elected by the wider Politburo membership in 2022, has seven members:

- Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist party (leader of PSC, Politburo and CCCPC), president of the People’s Republic of China and chairman of the People’s Liberation military.

- Li Qiang, premier of the State Council.

- Zhao Leji, head of the National People’s Congress.

- Wang Huning, chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.

- Cai Qi, first secretary of the secretariat of the Communist party.

- Ding Xuexiang, vice premier of the State Council.

- Li Xi, secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist party.

Government institutions

State Council 国务院

The State Council, also known as the central government, is the highest executive organ of state power in China and the highest organ of state administration. It is composed of a premier, vice-premiers, state councillors, ministers in charge of ministries and commissions, as well as an auditor-general and a secretary-general. It is responsible for managing China's internal affairs, from politics to education, as well as overseeing local governments. The functions of the State Council include implementing the regulations and laws adopted by the National People's Congress, China's top legislative body, as well as developing its own regulations. Each year, it drafts and delivers a “report on the work of the government” which summarises the nation's economic and social development at the “two sessions”.

State Council executive meetings 国务院常务会议

According to an official explainer, the State Council’s executive meetings discuss “major” and “significant” issues in the nation’s economic and social lives, then makes “final decisions” about them. They are chaired by the premier and attended by the vice-premiers, state councillors – who rank immediately below the vice-premiers – the secretary-general of the State Council, as well as the heads of relevant bureaus and ministries. Executive meetings normally take place every Wednesday.

Ministry of Ecology and Environment 生态环境部

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) is China’s ecological and environmental watchdog. It was established in 2018 by the National People's Congress to shoulder environmental-protection responsibilities previously spread among several ministries. Its main functions include formulating ecological and environmental policies in conjunction with other agencies, while also implementing these policies. China’s top economic planner, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), also manages environmental issues – but on a broader level, such as planning. The MEE and NDRC have the same seniority in China’s governing structure. Both are directly managed by the nation’s chief administrative authority, the State Council. The minister of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment from 2020 is Huang Runqiu from the Jiusan Society, a minor political party. He is the only minister that is not from the Communist party as of early 2025.

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) 国家发展和改革委员会发改委 (发改委)

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is China’s macroeconomic planner directly managed by the State Council, the nation’s chief administrative authority. It has broad administrative and planning control over the Chinese economy. The NDRC has an environmental resources division to oversee environment-related development and reform. It also supervises the National Energy Administration, which is in charge of China’s energy system. The NDRC has the same seniority as the Ministry of Ecology and Environment – another government organ that manages environmental issues – in China’s political structure.

National Energy Administration 国家能源局

The National Energy Administration (NEA) is the country's energy regulator and was established in 2008. It reports to the National Development and Reform Commission, the top planning body of the Chinese economy. It is responsible for formulating and implementing energy development plans and industrial policies, as well as promoting institutional reform in the sector. In addition, it is in charge of supporting significant scientific programmes and the research and development of important equipment. Its main functions also include managing nuclear power and directing energy conservation and the use of natural resources.