Climate change is likely to alter the way that the world grows, trades and enjoys food.

Warming temperatures could cause growing conditions to change – meaning that a crop that was once suited to its climate may need to be grown elsewhere. Rising temperatures in the oceans, too, could drive fish and other seafood out of their traditional range.

These shifting conditions could make it more difficult to produce traditional delicacies, which often rely on a combination of favourable climate conditions and local knowledge.

From the US hamburger to South Korea’s kimchi, Carbon Brief explores how some of the world’s most iconic traditional dishes could fare as the world warms.

Canada’s most well-known dish is poutine – a combination of french fries, cheese curds and gravy.

The country currently sources the majority of its potatoes domestically. Canada ranks 13th in the world for potato production and is also the second largest exporter of frozen french fries.

Canada’s potato crops face threats from extreme weather. Last year, the record northern-hemisphere summer heatwave caused prolonged hot and dry conditions in Canada, which affected potato growth. This was followed by heavy rain in the autumn, causing harvest disruption. The “unseasonable” weather forced farmers to abandon 6,475 hectares of potato crop – 4.5% of the total harvest.

“It’s unprecedented. Never, never before have I seen this in my time,” Kevin MacIsaac, general manager of the United Potato Growers of Canada, told the Toronto Star in December, 2018.

A study reported by Carbon Brief found that last summer’s northern-hemisphere heatwave “could not have happened without human-induced climate change”.

Several other studies have found that climate change is making extreme weather more severe in Canada. For example, research found that a severe drought that struck Canada’s western provinces in 2015 was made more likely by human-caused global warming. The region is home to 80% of the country’s arable land.

A recent study found that growing Canadian potato varieties in 35C caused potato size to shrink by up 93%. (During last year’s heatwave, this temperature was regularly exceeded in Eastern Canada, including Quebec and Ontatio, as well as in Western Canada, including in British Columbia and Saskatchewan.)

Separately, a study looking at the impact of climate change on global potato production found that parts of southern Canada could see yields decrease by 49% on 1979-2009 levels by 2055, if future greenhouse emissions are extremely high.

Another key ingredient of poutine is cheese curds, which are made from curdled milk.

Canada’s milk industry is concentrated in Quebec and Ontario which, together, are home to 82% of the country’s dairy farms. A study published in 2015 found that dairy cows in Southern Ontario are increasingly dying as a result of heat stress.

“As a result of climate change, heatwaves, which are defined as three days of temperatures of 32C or above, are an increasingly frequent extreme weather phenomenon in southern Ontario,” the authors write. “Heatwaves are increasing the risk for on-farm dairy cow mortality in southern Ontario.”

A second study published this year found that dairy cows in Quebec that were exposed to heat stress produced milk with less fat and protein. However, heat stress had little impact on the amount of milk produced by cows. “Further research is necessary to better understand the mechanism underlying the effects,” the authors say.

Poutine’s final key ingredient – gravy – can be made from various meats, but chicken is often used.

In 2018, Canada produced 1.3bn kg of chicken and 60% of this came from Quebec and Ontario.

A government report found that poultry farming in Quebec is “particularly sensitive” to heat stress. A heatwave in July 2002, for example, killed half a million chickens in the region – “despite the use of modern ventilation systems”, the report says. The incident revealed “the gravity of heatwaves” for poultry production, according to the report.

Though China’s cuisine varies from region to region, many consider its “national” dish to be Peking duck, which is served with a crispy skin.

China is the world’s largest domestic duck producer – with a census in 2010 finding that the country is home to nearly 2bn ducks.

The most common domestic variety is the Pekin duck, which is white with yellow feet. Pekin ducks are thought to have been bred from the mallard in south-east Asia around 4,000 years ago.

A scientific review of the impact of heat stress on poultry found that elevated temperatures could “cause reductions in the carcass, breast and thigh proportions” for birds including ducks. Heat stress can also impact “the intramuscular fat percentage in breast muscles which negatively affects the meat yield, nutritional value and meat taste”, the authors say.

A study conducted in the UK found that Pekin ducks are more likely to die when exposed to higher than average temperatures. “High ambient temperatures...were implicated in reduced growth rates [and] increased mortality,” the authors say in their research paper.

Carbon Brief analysis finds that average temperatures in China have increased by around 1.6C from the pre-industrial era to today. Temperatures could increase by a further 1.6C to 5.9C by 2100 – depending on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions released by humans.

Climate change is also increasing the frequency and intensity of heatwaves in China, according to several studies. For example, a recent study found Shanghai’s record-breaking heatwave in 2017 – in which temperatures reached 40.9C – was made 23% more likely to occur by human-caused climate change.

In addition to heat stress, duck farming could also face an increased risk of disease as the climate warms, studies suggest.

Domestic ducks in China are susceptible to a strain of bird flu that is deadly to humans, as well as to the ducks themselves. In 2013, the viral strain killed 623 people in China. Most of those infected had been in contact with farmed birds. In 2005 and 2006, a different strain of bird flu swept south east Asia – killing 140m domestic birds at a cost of $10bn.

Most harmful bird flu strains originate in wild water birds – and then spread into poultry populations, says Dr Marius Gilbert, a researcher of animal diseases from the Université Libre de Bruxelles and author of a research paper examining the impact of climate change on bird flu.

Climate change is expected to cause shifts to the lifestyles of wild water birds – by altering the path of their migrations, for example. These changes, in turn, could alter the spread of bird flu, making its impact on domestic ducks more unpredictable, Gilbert tells Carbon Brief:

“Climate change is likely to change the spatio-temporal distribution of wild bird migrations and, with it, the continental transmission of avian influenza viruses in general. But factors such as land use, for example, may have an equally strong effect on bird migration patterns...So disentangling the effect of changing climate is particularly difficult.”

A well-known traditional food in Costa Rica – and other Central American countries – is gallo pinto, which has a base of rice and black beans.

More than half of the country’s rice supply comes from domestic production, while the rest comes from imports – largely from countries in South America.

Costa Rica’s rice production faces threats from extreme weather, including heatwaves, flooding and tropical cyclones.

In October 2017, Costa Rica faced its costliest cyclone in history, when the fast-moving Tropical Storm Nate wreaked havoc across the country. Rice farmers in the primary production region of Guanacaste, in the northern Pacific side of the country, were “particularly affected” by the storm, according to a US government report.

“Some areas planted with sugarcane and rice in Guanacaste were completely flooded, and some remained under water for days after the storm,” the report says.

The storm was part of 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, which also saw Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria cause devastation across North and Central America. Research covered by Carbon Brief found the record-breaking run of hurricanes was largely driven by “pronounced warm conditions” in the tropical Atlantic Ocean.

Climate change is likely to have played a role in driving the unusually high Atlantic sea temperature, the lead author of the study told Carbon Brief, although natural factors could have also had an influence. Dr Hiroyuki Murakami, a researcher at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, told Carbon Brief in 2018:

“The effect of anthropogenic forcing [human influence] on sea surface temperature is difficult to be distinguished from natural variability so far. However, our experiments suggest that the effect of anthropogenic forcing actually leads to larger warming in the tropical Atlantic than the rest of the tropics and that, in turn, leads to an increase in major hurricane frequency.”

A study found climate change could cause smallholder rice crops in Central America to decline by 15-25% by 2050, if no new adaptation measures are taken.

Gallo Pinto’s other main ingredient, black beans, are grown domestically in Costa Rica, but also imported. Most imports come from neighbouring Nicuraga, but China and the US also supply the country with black beans.

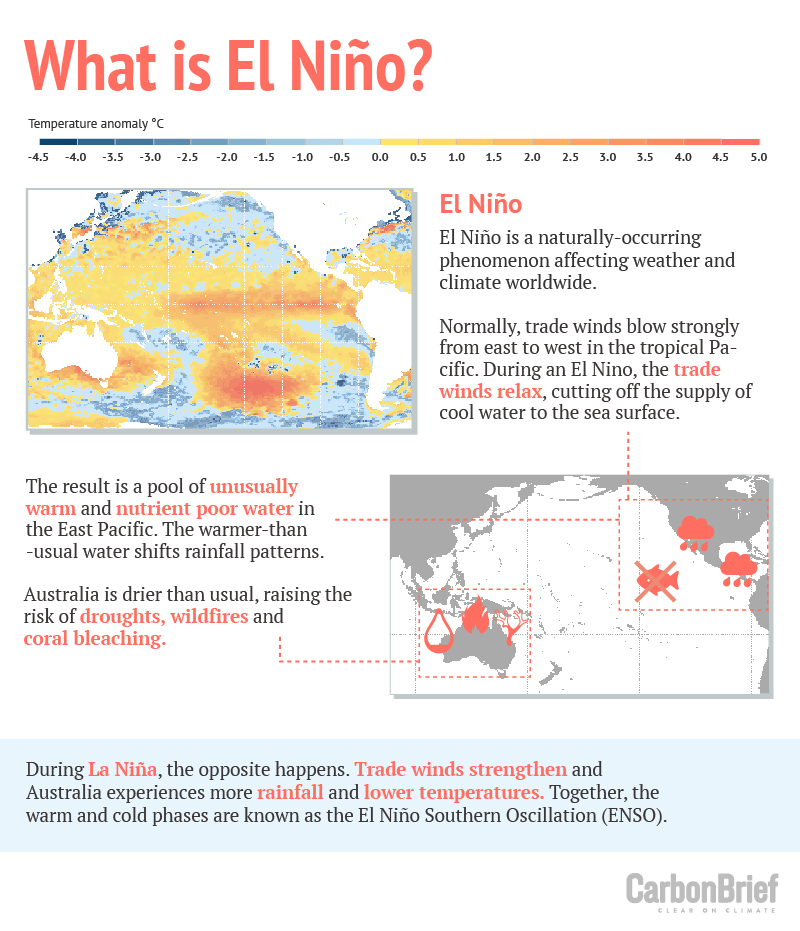

According to local news reports, the country frequently suffers from black bean shortages – sometimes as a result of the natural climate phenomenon El Niño.

A study covered by Carbon Brief found that the number of “extreme” El Niño events could double in frequency if global warming reaches 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, which is the aspirational temperature limit set by countries under the Paris Agreement.

One of Italy’s most iconic dishes is pasta. The country is the world’s largest pasta producer and exporter.

Pasta is traditionally made from durum wheat – a “hard” wheat that originates from the Middle East. Italy is the world’s second largest producer of durum wheat, but also imports large quantities of the grain, particularly from North America.

The majority of durum wheat production is carried out in southern Italy – though there are also growers in the central and northern regions. Crops are typically planted in October or November and harvested at the beginning of July of the following year.

This growing schedule makes crops particularly vulnerable to “early” heatwaves in the months of May and June. A study published in 2015 found that, from 1995-2013, years with early heatwaves also tended to experience higher durum crop yield declines.

Hot weather damages crop yields by “accelerating the plant developmental cycle” – leaving less time for the formation of grain, according to the study. Extremely high temperatures can “induce a wide variety of perturbations” to normal plant processes, it adds, which, if sustained, “can result in almost total yield loss”.

Crop losses reached a peak in 2003, the study notes, when a then “unprecedented” early summer heatwave swept Europe. The extreme event was made twice as likely by human-caused climate change, according to a landmark study.

Durum wheat farming also faces threats from other extreme events, including drought, heavy rainfall and severe frosts.

Research covered by Carbon Brief found that any amount of future climate change could increase drought risk in Italy – with southern Italy facing particularly high risks.

Even if future climate change is not severe, parts of southern Europe could see droughts that are “twice as bad as today”, Dr Selma Guerreiro, a researcher in hydrology and climate change from the University of Newcastle, told Carbon Brief.

Jamaica’s “national” dish is widely considered to be ackee and saltfish.

Ackee is a fruit native to West Africa that was first introduced to the island during the slave trade in the mid 1700s. The fruit is cultivated in Clarendon and St Elizabeth in southern Jamaica but ackee trees can be found across the island, including in gardens and along roadsides. The two main fruit-bearing seasons are from January to March and June to August.

Only the fleshy part of the fruit – the aril – is eaten. If ackee is eaten before it’s ripe, it can cause severe sickness and even death, particularly in children. This is because unripe ackee has high levels of hypoglycin A, a toxic amino acid.

Despite the fruit’s popularity in Jamaica, there has been very little research into how its production could be impacted by climate change, says Dr Sylvia Adjoa Mitchell, a senior lecturer in plant research at the University of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica.

One reason for this is the ackee tree is particularly hardy – and can currently cope well with extreme weather such as drought and hurricanes, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Basically, ackee in Jamaica has not been affected by climate change as the majority are not produced in orchards but in backyards. The trees do not succumb to long periods of drought and, within a few sessions of rainfall, respond by producing fruit. Hurricanes also do nothing more than prune the trees.”

However, it is not yet known how long-term changes in temperature and rainfall in Jamaica could impact ackee trees, she says.

The second main ingredient, saltfish, is a dry salt-cured white fish, typically cod. Jamaica relies on imports for its salted cod, with Norway being one of the biggest supplying countries.

A recent study covered by Carbon Brief found that cod in the North Sea – an important fishing ground for Norway – could be particularly vulnerable to rising ocean temperatures.

Each additional degree of ocean warming could cause sustainable yields of cod in the North Sea to decline by 0.44%, according to the study.

(The North Sea is warming twice as fast as the average for the world’s oceans. Average water temperatures in the North Sea have increased by 1.67C in the past 45 years and could rise by a further 1.7-3.2C by 2100, according to the German government.)

To read more on the impact of climate change on cod, please see the “UK” section of this interactive.

Sushi is one of Japan’s most well-known traditional foods. It comprises a combination of sushi rice and other ingredients, such as raw fish and vegetables.

The cuisine’s base ingredient – sushi rice – is typically made from Japanaese short-grain white rice.

Japan is the world’s ninth largest rice producer and the staple is grown in “paddies” across the country. A paddy field is a flooded section of arable land that is used for growing rice, which is a semi-aquatic plant.

The country’s rice crops face threats from rising temperatures. However, the risks vary from region to region, with research suggesting that Japan’s most northerly regions could see more favourable conditions for growing rice as temperatures rise, while other areas could see less favourable conditions.

For example, research found that global warming of 3C could cause rice yields in Hokkaido, the northernmost of Japan’s islands, to increase by 13%. In contrast, rice yields in the Tohoku district, northeast of the country’s main island, could decrease around 10%, according to the research.

Some Japanese varieties of rice could see increased yields as CO2 levels rise, research found.

This is due to a phenomenon known as the “CO2 fertilisation effect”. This occurs because plants need CO2 to carry out photosynthesis. With more CO2 in the atmosphere, plants carry out photosynthesis at a faster rate and, thus, grow more quickly.

Though rising CO2 levels could boost rice yields, they may also cause the crop to become less nutritious, separate research has found. Previous experiments have shown that rice crops exposed to high CO2 levels produce less iron, protein and zinc.

Like other crops, Japan’s rice also faces threats from extreme weather, including heatwaves. Several studies have shown that recent heatwaves in Japan were made more likely or more severe by climate change.

A recent study covered by Carbon Brief found that Japan’s record 2018 heatwave – in which more than 1,000 people died – “could not have happened without human-induced global warming”.

Climate change has also caused an increase in heavy rain events in Japan, which can lead to the flooding of rice crops.

The impacts of flooding can be long-lasting. This summer, farmers in Higashihiroshima – a major rice-producing area – were left unable to plant new crops after their paddies failed to recover from heavy flooding in the region last year, according to the Japan Times.

A fish commonly used in sushi in Japan is tuna, including the critically endangered bluefin tuna. Up to 80% of the world’s bluefin tuna catch is used for sushi and sashimi in Japan.

A study looking at the impact of climate change on six of the seven commercially fished tuna species found that almost all populations are likely to shift poleward as the ocean warms. If future global warming is extremely high, populations of albacore tuna just south of Japan are likely to decrease, the study says.

South Korea’s national dish is kimchi, a side dish of fermented vegetables including napa cabbage and Korean radish.

Napa cabbage – also known as Chinese cabbage – is popular in East Asian cuisine but is also sold in supermarkets across Europe and North America.

In South Korea, 90% of the napa cabbage cultivated is “earmarked for kimchi”, according to a US government report. “For most Korean families, kimchi-making takes place at the beginning of winter for consumption throughout the coming winter and spring and requires a group effort for a few days,” the report says.

South Korean farmers produce 2.5m tonnes of napa cabbage each year, according to government figures. Cabbage cultivation is threatened by extreme weather, including heatwaves and heavy rains.

In 2010, the country faced a “kimchi crisis” when a bout of extreme weather destroyed half of all cabbage crops. The damage caused the price of cabbage to more than triple, according to NPR, which led to a nation-wide scramble for the vegetable.

The crop damage came around as a result of “a freakish combination of cold temperatures in the spring, an extreme heatwave in the summer and torrential rains in September”, NPR says.

A series of studies have found that climate change is increasing the chances of severe heatwaves in the country. For example, a study found that the extreme temperatures seen in South Korea’s 2013 heatwave were made “10 times more likely by climate change”.

The country has also seen an “early onset of summer” in recent years, with temperatures ramping up in May instead of June. A study found that the early summer of 2017 was made “two to three times more likely” by climate change.

A separate study published in 2018 found that climate change is likely to make severe rainfall more common in South Korea.

To study the future impact of climate change on napa cabbage, a group of scientists conducted an experiment where the crop was grown in various conditions that mimicked future warming.

In greenhouses, cabbage was grown in temperatures that were either 3.4C or 6C above average – mirroring scenarios of “moderate” or “extreme” climate change. Scientists also grew cabbages in current conditions.

They found that cabbages grown under 3.4C of warming had yields that were 65% lower than cabbages grown under current conditions. “These results suggest that climate change scenarios may have a profound impact on the cultivation of Kimchi cabbage,” the authors say.

A staple food in Uganda – and its neighbouring regions – is matooke, a type of green banana native to the region, which is usually served mashed.

The banana is well adapted to being grown in East African highland conditions, where temperatures are typically cooler than at lower elevations, says Prof James Dale, a researcher of African banana varieties from the Queensland University of Technology in Australia. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Matooke requires a typical banana environment: at least one metre of rain per year, warm temperatures and no frost. The climate doesn’t have to be hot. In Uganda, there are plantations growing close to 2000m. It is quite cold at night at that elevation.”

Matooke crops are typically rain-fed and so vulnerable to long-term shifts to rainfall driven by climate change, Dale says:

“Climate change is already having an impact. Uganda used to have a long wet season and a short wet season. These were extremely reliable and farmers would plant their annual crops based on the date the wet season should arrive. The wet season's reliability is shot. Rains come late and then peter out quickly. Drought is now becoming a major production problem.”

Research found that, across Uganda, rainfall has decreased by 12% over the past 34 years. This decrease is highest in “agricultural regions of central and western Uganda” – where matooke is cultivated, the study notes.

Further studies found that two major droughts in East Africa – in 2011 and 2014 – were made both more severe and more likely to occur by climate change.

Drought has become “a major yield loss factor” for matooke, according to another study. In an observational experiment carried out from 1996-2009, the authors found “every 100mm decline in rainfall caused maximum bunch weight losses of 1.5-3.1kg, or 8-10% [of the total bunch weight]”.

“At the moment the disease challenges and threats are more important than climate change [for matooke production],” says Dale. Production is currently hampered by diseases including Black Sigatoka and Banana bacterial wilt, he says, as well as by pests such as the banana weevil.

“However, if the trend of reduced and intermittent rains continues this will become a major limiting factor. This will be a huge challenge for most crops in Uganda.”

A review of climate change’s impact on food production in the East African Highlands found that the land suitable for banana production could decline by 40% by the end of the century – largely as a result of declines in rainfall.

One of the UK’s most well-known dishes is fish and chips, traditionally made with cod coated in batter and thick-cut potatoes – both of which are served deep-fried.

The UK sources the majority of its cod from its surrounding waters, including from the North and Irish seas.

Despite what it is implied by some overzealous headlines, the largest threat facing cod populations in this region is overfishing – rather than climate change.

Cod numbers in the North Sea are now at “critical” levels following sustained overfishing, according to a recent report from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (Ices).

However, climate change could compound the risks posed by overfishing.

A study found that cod populations in the North and Irish seas are particularly vulnerable to ocean warming. It found that each additional degree of ocean warming could cause the amount of cod that can be caught sustainably in the North and Irish Seas to fall by 0.44 and 0.54%, respectively.

(The North Sea is warming twice as fast as the average for the world’s oceans and has seen 1.67C of temperature rise in the past 45 years. The Irish Sea has seen around 1C of temperature rise in the past 40 years, according to the UK government (pdf).)

The declines could be down to climate change’s negative impact on “zooplankton” – the microscopic marine animals that cod feed on, according to the research.

Together, the threats of overfishing and climate change present a “one-two punch” to cod populations, Dr Chris Free, a researcher from the University of California, Santa Barbara, told Carbon Brief in February. He said:

“Overfishing makes fisheries more vulnerable to warming, and continued warming will hinder efforts to rebuild overfished populations.”

The meal’s other key ingredient – chips – could also face significant threats from climate change. The UK is the world’s 11th largest potato producer and 80% of the potatoes eaten in the country are grown domestically.

Potatoes are grown outdoors in the UK and so are “particularly sensitive” to changes in rainfall, temperature and soil quality, according to a recent report commissioned by the Climate Coalition, a group of climate-focused not-for-profit organisations.

Temperature increases and changes to rainfall could cause the land suitable for potato production in the UK to decline by 74% by 2050, according to the report.

Potato production also faces threats from extreme weather, including droughts and heatwaves.

Last summer’s extreme heatwave – which scientists say was made up to 30 times more likely by climate change – played a role in driving a 20-25% decline in potato yields in some areas as the hot and dry conditions damaged crops, according to the report.

The declines may have even led to a decrease in the size of chips available in the UK, according to one interviewee. “[Chips] were 3cm shorter on average in the UK [following the heatwave],” said Cedric Porter, editor of World Potato Markets, according to the report.

Potato crops also face rising threats from pests and diseases moving poleward as temperatures rise, the report says:

“The roundworm pest potato cyst nematode already causes losses of approximately £50m per year to UK growers. That figure is predicted to rise with the pest benefiting from warmer soil and air temperatures due to climate change.”

The hamburger is thought of as a classic US meal. Traditionally, the main ingredient is a beef “patty”.

The US is the world’s largest producer of beef and is home to more than 30m beef cows. Domestic production makes up the majority of the beef supply – with 8-20% coming from imports. Canada and Mexico are the main foreign suppliers.

Beef rearing is concentrated in the warmer states such as Texas and Florida – where near year-long grass is available. However, as temperatures rise, these regions could become intolerably hot for cattle, according to a federal report.

Cows are particularly sensitive to heat because they cannot sweat, explains Prof Grant Dewell, a beef cattle vet at Iowa State University. In a blog post, he writes:

“Cattle do not sweat effectively and rely on respiration to cool themselves. A compounding factor on top of climatic conditions is the fermentation process within the rumen [stomach] generates additional heat that cattle need to dissipate.”

Warm temperatures can also weaken cattle’s immune system, leaving them more susceptible to disease. Female cows also spend more time seeking shade when it is hot, meaning they are less likely to get pregnant and produce offspring.

Climate change could also affect the availability of the grasses that cattle feed on. Federal research found that rangelands in the southwestern US could have “diminished capacity to support cattle” in the future as warmer conditions could cause shifts to the types of vegetation available to cows.

US cattle also face threats from increasingly severe heatwaves. A 2011 heatwave led to the death of 4,000 cattle in the state of Iowa alone. At the time, some farmers attempted to cool their herds by installing “industrial sized fans”, according to Farm Progress.

A series of studies have found that climate change is making US heatwaves both more likely and more severe. For example, a study found that the 2011 heatwave in Texas – the largest state for beef production – was made 10 times more likely by human-caused climate change.

Livestock also face threats from other types of extreme weather, including blizzards and floods. This year, blizzards and flooding in the midwest in March led to cattle deaths costing $400m in the state of Nebraska.

The impact of climate change on blizzards and cold spells is still uncertain. A study conducted in 2014 found that blizzards in the nearby state of Dakota may be occurring less frequently as the climate warms.

However, a growing field of research suggests that warming in the Arctic could be playing a role in driving extreme cold snaps in the US. In January, Carbon Brief published a detailed explainer exploring the links between extreme cold in the US and Arctic warming.