This article is part of a week-long special series on loss and damage.

This year has seen thousands of people killed in a run of unprecedented extreme weather events. Catastrophic flooding has caused at least 1,500 deaths in Pakistan in recent weeks, while record heat has blighted much of the globe – for example, killing 1,000 people in Portugal and Spain in July.

The loss of human lives in extreme weather events is the most visceral example of “loss and damage”, a term used to describe how people – particularly the poor and vulnerable – are already reeling from the impacts of human-caused climate change, which is predominantly driven by the emissions of a wealthy minority.

From the loss of low-lying island territory to rising seas through to homes and businesses destroyed by cyclones, loss and damage from climate change is already vast and far-reaching.

At this year’s UN General Assembly, UN chief António Guterres raised the alarm on loss and damage, describing it as a “fundamental question of climate justice, international solidarity and trust” – adding that “polluters must pay” because “vulnerable countries need meaningful action”.

Though the issue of loss and damage has been discussed for more than 30 years, it is fast emerging as one of the most critical issues at the UN climate talks.

At the last UN climate summit in 2021, COP26 in Glasgow, a group of largely developing nations representing six out of every seven people in the world called for developed countries to commit to pledging funds for loss and damage. However, this call faced opposition from large economies such as the US and EU – and, ultimately, was rejected.

It is expected that loss and damage will be one of the dominant themes at COP27, the next round of UN climate negotiations taking place in Egypt in November.

Ahead of the conference, Carbon Brief has produced an interactive explainer on – according to experts – what loss and damage is, who is responsible and how it should be paid for. It is the first in a week-long series of articles examining the key aspects of loss and damage.

This article is part of a week-long special series on loss and damage.

“Loss and damage” is a term used to describe how climate change is already causing serious and, in many cases, irreversible impacts around the world – particularly in vulnerable communities.

Prof Saleemul Huq, the director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) and a pioneer of loss and damage research and advocacy, tells Carbon Brief:

“The term loss and damage means the impacts of human-induced climate change affecting people around the world. Damage refers to things that can be repaired, like damaged houses, and losses refer to things that have been lost completely and won't come back – like human lives.”

Ineza Umuhoza Grace, a Rwandan activist and director of the Loss and Damage Youth Coalition (LDYC), adds:

“We are losing infrastructure, losing our agricultural land – and losing what we can call a hope of having sustainable economic growth and a future for everybody.”

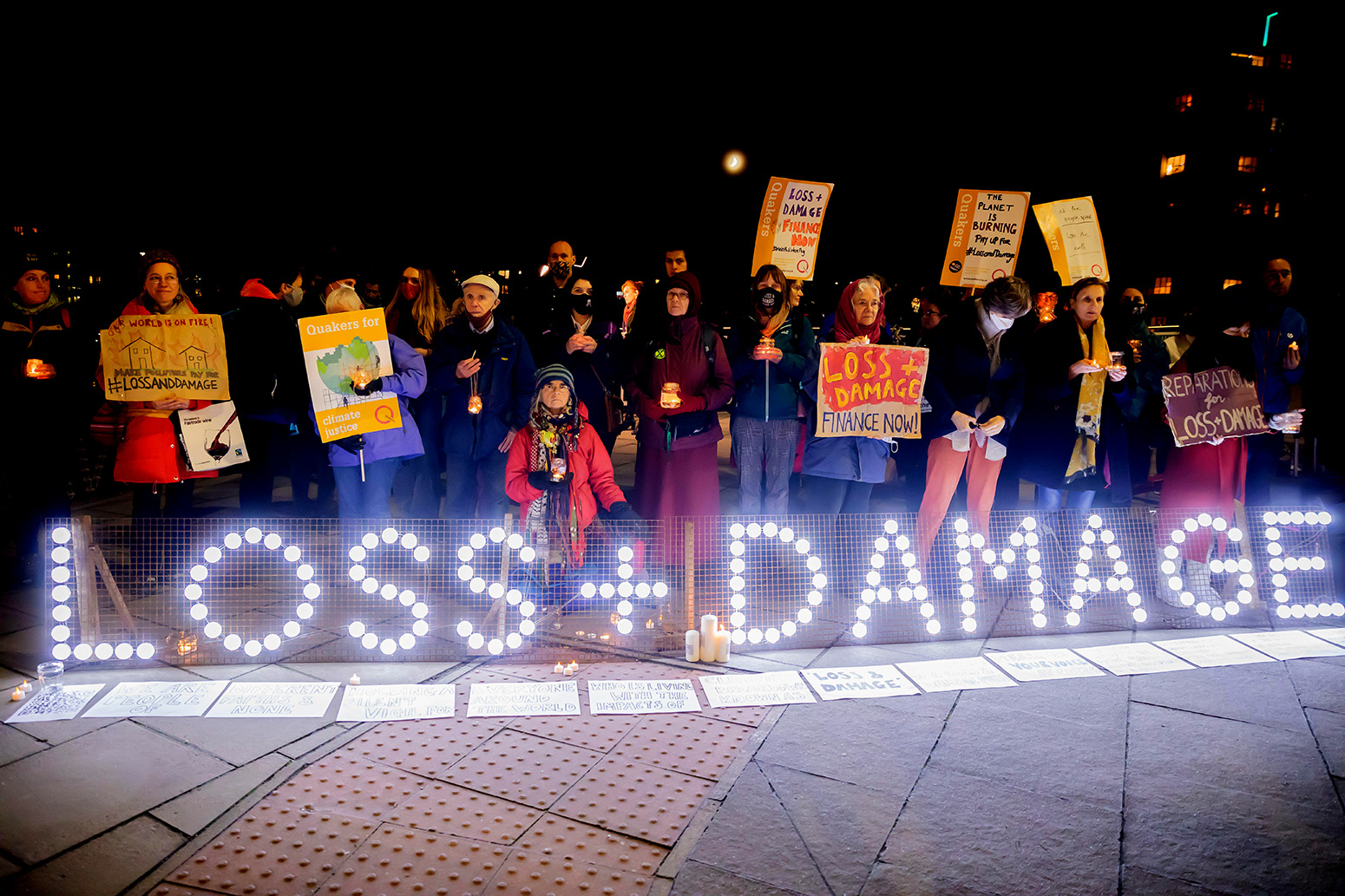

At UN climate talks, the term is used by nations and organisations arguing for developed, high-emitting nations to be held responsible for losses incurred in poorer regions, which are the least responsible for climate change. (Because of this, the term “loss and damage” is sometimes described as meaning “climate reparations”.)

These groups have called for the creation of a “loss and damage finance facility” – a fund paid by large emitters to assist vulnerable people dealing with loss and damage caused by climate change.

They argue this is needed because money pledged towards tackling climate change is currently only directed towards either efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (“mitigation”) or adaptation measures to protect against rising warming impacts.

Neither stream of funding is specifically designed to give aid to those who have experienced loss from climate change, such as the loss of a loved one in a heatwave, or damages, such as damage to property or agricultural land in a cyclone.

Harjeet Singh, a senior advisor and loss and damage expert at Climate Action Network, explains to Carbon Brief:

“This system [the UN] has money if you want to put up solar panels, it has money if you want to retrofit your home (of course, not enough), but it doesn’t have money when people are losing their homes. It’s a clear gap.

“Somebody who is drowning, we say: ‘We can’t help you now, but if you survive we may help you prepare for a future disaster.’”

Loss and damage can be caused by immediate climate impacts, such as more intense and frequent extreme weather events, as well as impacts that gradually worsen over time, such as sea level rise and the retreat of glaciers.

The study of how climate change is affecting the likelihood and severity of extreme weather events is known as “attribution science”. (See Carbon Brief’s detailed explainer and interactive map.)

In its most recent report on the impacts of climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that “human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe”.

It is “virtually certain” that heatwaves have become more frequent and more intense since the 1950s, the report says, with human-caused warming being “the main driver” of these increases.

Many heatwaves seen over the past decade would have been “extremely unlikely to occur” without human-caused climate change, according to the report.

Carbon Brief’s own analysis of 504 extreme weather events and trends finds that 71% were made more likely or more severe by human-caused climate change.

The chart below shows the number of studies that have been conducted into different types of extreme weather events, including heatwaves, floods and extreme rainfall events, and droughts, among others.

On the chart, colour indicates the proportion of studies that found climate change made the event more severe or more likely to occur (red), less severe or less likely (blue), where climate change had no effect (peach) and where there was insufficient data to draw conclusions (grey).

In its most recent report on the impacts of climate change, the IPCC concluded that the loss of ice from glaciers reached its highest level since records began over the past two decades.

Meanwhile, global mean sea level rise is currently at its highest rate in at least three million years, according to the IPCC.

According to the IPCC, loss and damage can broadly be split into two categories:

It says that the “overall adverse economic impacts” of extreme weather events and slow-onset events, such as sea level rise and glacier loss, have so far been detected in industries including agriculture, forestry, fishery, energy and tourism – and through the loss of outdoor labour during climate extremes.

A separate UN report from the World Meteorological Organization published in 2021 found that economic losses from climate and weather disasters have increased sevenfold over the past five decades.

(A climate or weather event is considered a disaster if it kills at least 10 people, affects at least 100 people, a declaration of a state of emergency is made, or a country makes a call for international assistance.)

Hurricanes and storms caused the highest amount of economic damages out of any kind of climate and weather disaster over the past 50 years, the report said.

It added that three of the costliest 10 disasters in the past 50 years occurred in 2017. This includes hurricanes Harvey (which caused $97bn in damages in Texas), Maria (which caused $70bn in damages in the Caribbean islands of Dominica, Saint Croix and Puerto Rico) and Irma (which caused $58bn in damages across the Caribbean and the US).

When compared to economic loss and damage, non-economic loss and damage is less well studied and reported on, according to the IPCC:

“Economic losses and damages from climate change are often assessed and reported after disasters or within crises. However, non-economic losses from climate change are often overlooked.”

In many ways, intangible loss and damage has become a catch-all term for any type of loss that cannot be valued in monetary terms, says Prof Neil Adger, a researcher of environmental geography at the University of Exeter. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We’ve got a category of things that are economic – and then we’ve got a category of things that we should really care about. Economics looks pretty unimportant if there’s a risk you’re going to lose your life.”

A scientific review published in 2019 was the first to comprehensively summarise all of the ways that climate change can lead to non-economic loss and damage.

It says that intangible loss and damage can result from climate-induced harm to:

Not all countries are affected equally by the impacts of climate change. The chart below shows the average number of people affected by extreme climate-related events per 1,000 in the 20 lowest (blue) and highest (red) income countries, over 1990-2019.

The most severe climate impacts are often faced by people in the least wealthy countries – who generally have the smallest contributions to global emissions. As such, loss and damage has become an important issue in discussions of climate justice.

Huq tells Carbon Brief that the “least developed countries” – as defined by the UN – are “victims of climate change”. He adds:

“But their own emissions are less than 5% of global emissions. So they don't cause the problem. But [they are] the overwhelming populations in which countries are suffering already – not just going to suffer, but already suffering.”

The economic impact of climate change is determined by both the severity of the impacts and the vulnerability of local communities, which can be exacerbated by unrelated factors such as poor governance and lack of investment.

Small island nations are said to be “on the frontlines of climate change” due to a combination of severe climate impacts and inadequate adaptation funding, which makes them highly vulnerable to climate impacts such as flooding.

As such, small island developing states are already suffering some of the greatest economic losses from climate change. The chart below shows the 20 countries with the highest economic losses from extreme climate-related events over 1990-2018, as a percentage of GDP. Small island developing states are shown in dark blue.

By 2100, a central estimate of more than 100 metres of shoreline retreat is projected for all small islands under both mid (RCP4.5) and very high (RCP8.5) emission scenarios. This would be a great threat to many small island nations, which could lose some islands completely as a result of sea level rise.

The IPCC’s latest assessment report has a chapter dedicated to small island nations, which states:

“It has long been recognised that greenhouse gas emissions from small islands are negligible in relation to global emissions, but that the threats of climate change and sea level rise to small islands are very real. Indeed, it has been suggested that the very existence of some atoll nations is threatened by rising sea levels associated with global warming.”

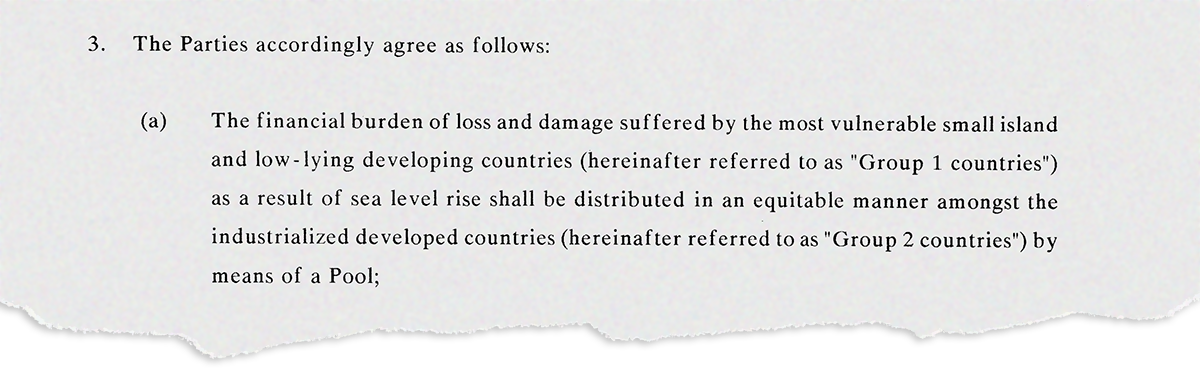

The first call for action on loss and damage, shown below and issued in 1991, came from the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) – a group that today represents 39 small island and low-lying coastal developing nations in international climate negotiations.

Since then, small island states have “consistently tried to highlight the issue of loss and damage”, Yeb Saño, former Philippines negotiator and Greenpeace Southeast Asia executive director, tells Carbon Brief.

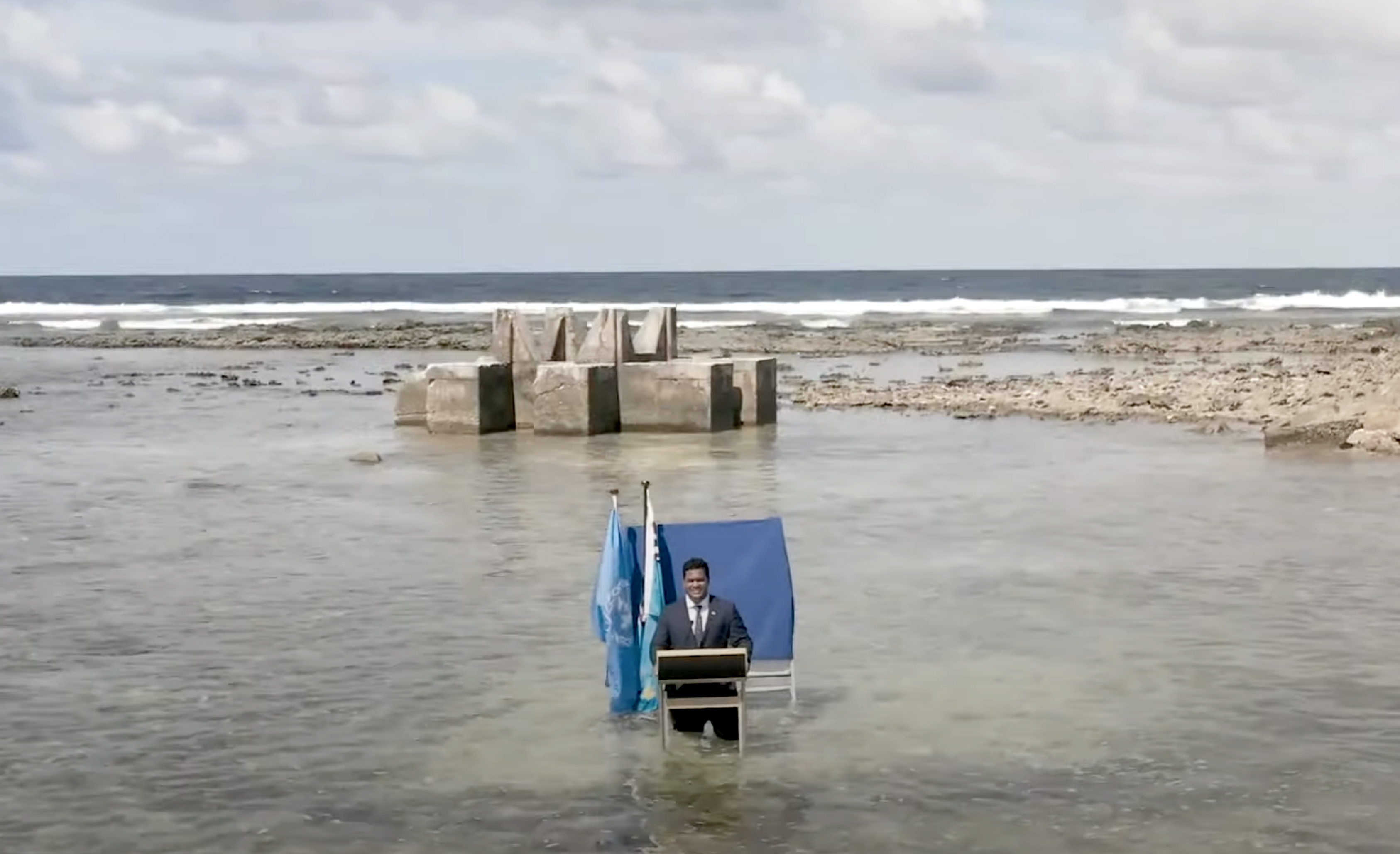

More recently Simon Kofe, the foreign minister of Tuvalu – a series of low-lying Pacific islands – addressed the COP26 conference in a video standing knee-deep in seawater to highlight the dangers of sea level rise for his nation.

Tuvalu is considered the first island nation that could become uninhabitable as a result of climate change and, consequently, lose its sovereignty, since land is the “baseline from which exclusive economic zones are calculated”.

The average land elevation in the archipelagic state is just two metres above mean sea level, and the water is rising at almost 0.5cm each year.

Meanwhile, small-island developing nations are calling for greater action on loss and damage at COP27.

Small island states are pushing to formally get loss & damage on the agenda at COP27

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) September 15, 2022

"it is imperative that govts show their leadership in the fight against the climate crisis by calling for the advancement of loss and damage response finance at…COP27"https://t.co/8n7bXUTnFT pic.twitter.com/f9JRz7K1QN

Small island nations are not the only countries pushing for greater emphasis on loss and damage. For example, Africa and the Middle East – which contain some of the poorest nations in the world – have become increasingly vocal in recent years about the impacts of loss and damage in their countries, as well as the need for richer countries to assist with loss and damage finance.

While loss and damage is most notable in lower income countries, richer nations also face economic damages from the impacts of climate change.

For example, the US has sustained 332 weather and climate disasters since 1980 in which overall damages reached or exceeded $1bn – with a total cost of more than $2.28tn. Tropical cyclones are the most costly extreme weather events in the US – but floods, droughts and fires also impact the country.

In wealthy nations, poorer communities and minorities often experience the most severe climate impacts. For example, research suggests that climate change and population growth could drive a 26% rise in US flood risk by 2050 – disproportionately impacting black and low-income groups.

Meanwhile, Carbon Brief analysis shows that, in general, women are more likely to die or suffer injury in extreme weather events. And separate research shows that people with disabilities are also particularly at risk from the impacts of climate change.

Wealthier nations are often more able to pay for the impacts of climate change than developing nations. When floods hit western Germany in 2021, causing an estimated €40bn in damages, the government allocated €30bn for repairs. Another €8.2bn was paid by insurers.

Dr Elisa Calliari, a loss-and-damage researcher at University College London, tells Carbon Brief that loss and damage “is still largely framed as something concerning vulnerable developing countries”. She adds:

“During negotiations I’ve heard some developed countries referring to the losses and damages experienced in their national context, in particular, by indigenous communities. My impression is that this felt to some developing countries as an undue ‘appropriation’ of the concept and a way to divert attention from developed countries’ historical responsibility for loss and damage.”

The “global south” is a term used to broadly describe lower-income countries in regions such as Africa, Asia and Latin America. It is often used to denote nations that are either in the process of industrialising or are newly industrialised, as well as those that are the former subjects of colonialism. It does not refer directly to the southern hemisphere and, indeed, many nations falling into this category are located north of the equator. As with overlapping terms such as “Third World” or “developing”, it is not universally accepted and is an imperfect way of describing a large group of countries with very different histories, cultures and economies. The term is often used in discussions about climate justice.

However, other experts told Carbon Brief that, in their view, it is appropriate to expand the definition to richer nations, as long as global inequality is noted.

The “global south” is a term used to broadly describe lower-income countries in regions such as Africa, Asia and Latin America. It is often used to denote nations that are either in the process of industrialising or are newly industrialised, as well as those that are the former subjects of colonialism. It does not refer directly to the southern hemisphere and, indeed, many nations falling into this category are located north of the equator. As with overlapping terms such as “Third World” or “developing”, it is not universally accepted and is an imperfect way of describing a large group of countries with very different histories, cultures and economies. The term is often used in discussions about climate justice.

Dr Chandni Singh, an expert in climate change and development in the global south at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, noted the global inequality in climate impacts and adaptive capacities, but told Carbon Brief:

“In principle, I don't think broadening the definition to the global north is a problem, especially because we need to recognise impacts on the most vulnerable within global north countries.”

Who bears responsibility for loss and damage is a question right at the heart of debates surrounding the issue.

If someone dies in a flood in Bangladesh, which was made more likely by human-caused climate change, who is to blame? Is it countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions? Wealthy nations that got rich by burning fossil fuels? Wealthy individuals? Or fossil fuel companies themselves?

It is a question with no easy answer. One way to address it is to compare how different groups have contributed to climate change.

This chart shows countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. It demonstrates that China, the US, India and Indonesia are currently the world’s biggest emitters on an annual basis.

This chart shows which countries have contributed the most to climate change since the start of the industrial revolution in the 1800s. It demonstrates that, from the start of the industrial era to 2019, the US has caused the most emissions, with the UK also featuring in the top 10.

This chart shows countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, when they are divided per person living in that country. It demonstrates that the sparsely populated Solomon Islands has the highest “per-capita” emissions, with oil-producing Qatar and Kuwait also featuring in the top 10.

This chart shows the 20 private and state-owned fossil fuel companies that have contributed the most to global emissions between 1965 and 2018. These companies accounted for 35% of all energy-related greenhouse gas emissions in this time period, according to the data.

This chart shows countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. It demonstrates that China, the US, India and Indonesia are currently the world’s biggest emitters on an annual basis.

This chart shows which countries have contributed the most to climate change since the start of the industrial revolution in the 1800s. It demonstrates that, from the start of the industrial era to 2019, the US has caused the most emissions, with the UK also featuring in the top 10.

This chart shows countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, when they are divided per person living in that country. It demonstrates that the sparsely populated Solomon Islands has the highest “per-capita” emissions, with oil-producing Qatar and Kuwait also featuring in the top 10.

This chart shows the 20 private and state-owned fossil fuel companies that have contributed the most to global emissions between 1965 and 2018. These companies accounted for 35% of all energy-related greenhouse gas emissions in this time period, according to the data.

(It’s also possible to look at historical responsibility in relation to current or historic populations, as shown in Carbon Brief’s analysis of past emissions.)

For many of those calling for the world to establish a loss-and-damage fund at UN climate talks, it is developed nations – who are among the largest emitters since the start of the industrial era – that should be held responsible. Prof Saleemul Huq tells Carbon Brief:

“Loss and damage is directly attributable to the fact that we've raised global mean temperature by 1C because of the emissions of greenhouse gases that have taken place since the industrial revolution. The major emitters of those greenhouse gases have a responsibility to compensate the victims of the impacts of climate change.”

These groups – including the “G77 plus China” coalition of 134 developing countries and China – argue that the idea of developed nations being responsible for loss and damage is in line with the principles of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the global treaty for tackling climate change established in 1994.

The convention specifically “puts the onus on developed countries to lead the way” on climate change, the UNFCCC website says, acknowledging that these countries are the “source of most past and current greenhouse gas emissions”.

“The UNFCCC is the ultimate international body that needs to deal with this,” says Sandeep Chamling Rai, a senior advisor at the environmental charity WWF and an expert on the UNFCCC non-economic loss and damage taskforce.

But, at past UN climate talks, wealthy parties such as the US and the EU have blocked moves that could have led to them being held responsible for loss and damage.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Daniel Bodansky, a law professor at Arizona State University and a former climate change coordinator for the US State Department, says that the US view is that blaming countries for their past emissions could, ultimately, be unproductive. He says:

"The US view generally has been that the regime will be much more productive if it's forward looking. Because if the climate regime is backward looking – trying to assign blame for what's happened, which would then provide a basis for liability and compensation – countries aren't going to participate. The US will run away from the international climate regime. I think China is extremely unlikely to want to go there…It's just not going to be politically possible to do that."

He adds that assigning responsibility to large emitters raises “philosophical issues”:

"It's very difficult to know how to assign blame – a lot of the emissions were before people were even aware of climate change as a problem. Should you be holding people responsible for that? What is the theory of responsibility for historical emissions?”

However, if wealthy nations do not accept responsibility for their past emissions, poorer nations may feel discouraged to contribute to climate action going forward, says Huq:

“In my view, loss and damage is by far the most important global climate goal. Because, for 30 years, we haven't taken the actions to prevent loss and damage, it's now happening and so on our shoulders to deal with it. That is by far the first thing that we have to do to tackle climate change, the other [goals] can come later.”

Speaking to Carbon Brief in June while still in office, the former UN climate chief Patricia Espinosa said that loss and damage is an issue that all countries need to “discuss in the most open manner with the best intentions”. She added:

“We need to overcome some mistrust among countries and really address the issue…Avoiding the discussion is not something that will resolve the issue…We need to sit together and find the right solutions and the right instruments in order to get those financial resources. And, yes, a part of those resources need to come from the governments of the developed countries.”

Outside of UN climate negotiations, there is a growing movement of lawyers, activists and policymakers that are aiming to hold both wealthy countries and fossil-fuel companies accountable for their emissions in the courts.

According to a recent report on global climate litigation trends, the number of climate change-related cases has more than doubled since 2015.

So far, none of these cases have specifically centred on loss and damage, according to the report.

However, it notes a new legal effort from Antigua and Barbuda, and Tuvalu, who officially launched a Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law at COP26 in 2021.

The commission’s mandate explicitly includes “the responsibility for injuries arising from internationally wrongful acts” that may result from states’ breach of their obligations to protect the marine environment, which – according to the report – “could be considered commensurate with a mandate to explore legal recourse for loss and damage”.

This, coupled with a separate legal effort from the small island Vanuatu, could see loss and damage featuring centrally in climate litigation cases within the next year, the report says:

“The new commission, coupled with Vanuatu’s announcement…may suggest that this [loss and damage] debate may soon move beyond the largely theoretical realm in which it has existed to date.”

The term “loss and damage” emerged from UN climate negotiations, where diplomats from almost every nation meet regularly to discuss measures to tackle climate change.

It has a long, fraught history in the process that pre-dates the launch of the UNFCCC in 1992.

For years, developing countries have petitioned developed countries to provide them with more money to deal with loss and damage. Their efforts so far have been unsuccessful.

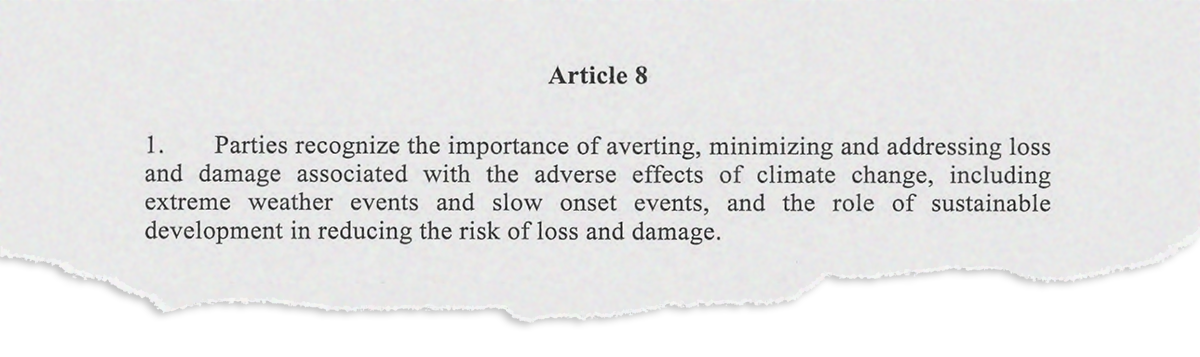

However, when years of negotiations culminated in the Paris Agreement in 2015, the landmark climate treaty included important references to loss and damage.

It separated loss and damage from adaptation in its own “article” of the treaty – Article 8 – making it clear that this was a distinct and important issue that required action, alongside cutting emissions and adapting to climate change.

The agreement established the importance of “averting, minimising and addressing” loss and damage. While the first two of these goals can be viewed as overlapping with climate adaptation actions, campaigners are increasingly focusing on the “address” part of this mandate, which is seen by many groups as justification for new loss-and-damage finance.

The Paris Agreement was also accompanied by a “decision text”, according to which the treaty would not provide the basis for liability and compensation claims on the basis of loss and damage.

This was reportedly an important issue for the US and other developed countries that feared being held legally accountable for their own historical contributions to climate change. (See: How should loss and damage be paid for?)

UN talks have also established two key institutions that have helped to advance and popularise the concept of loss and damage at an international level.

These are the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts (WIM) and the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage – both named after the capital cities of the COP presidencies in the year of their origin.

The WIM was established in 2013 by a formal legal decision of the COP19 talks, following efforts by vulnerable countries to get loss and damage on the agenda at UN talks.

The WIM has three core functions:

The first function refers to improving the collection of relevant data, something that is much less prevalent in low-income nations and communities. Enhancing knowledge involves identifying who needs help and what their requirements are.

The second function concerns the sharing of resources and collaboration between the various local groups, international charities, government agencies and other bodies that have responsibility for tackling loss and damage.

The third function is the most contentious, because, in theory, it could include mobilising funds to pay for the impacts of climate change. However, in practice, it has been the most overlooked aspect of the WIM’s mandate and progress in this area has been slow.

This slow progress has been attributed to developed country negotiators involved in the process wanting to avoid the risk of compensation payments.

The WIM’s work is overseen by its executive committee (ExCom) which is made up of 20 national representatives from countries that participate in UN climate talks, including a mix of developed and developing nations.

After an initial two-year workplan to explore action areas, lasting from 2015 to 2017, the ExCom began a five-year workplan that is up for renewal in 2022.

This consists of five workstreams, each of which has had a group of experts assigned to it. Between them, they cover slow-onset events, non-economic losses, risk management, displacement and “action and support”.

Of these, the action and support group, which covers finance, was established last and – according to Harjeet Singh of Climate Action Network – only after a political fight in 2019.

He tells Carbon Brief that the WIM could have been responsible for mobilising loss-and-damage finance if the participating developed countries had allowed this to happen:

“There was no need for all the political drama that has happened over the last few years, [if] we had that body that…[had] actually acted in good faith.”

The Santiago Network was established as part of the WIM at COP25 in 2019, following a review of the mechanism. Its stated aim is to help “catalyse” and connect developing countries with the technical assistance and expertise they need to tackle loss and damage.

In practice, its funding and governance arrangements are still up for debate, after discussions continued at COP26 and beyond. As it stands, climate NGOs say it is little more than a website, while noting that it has the potential to help developing countries deliver support on the ground.

As nations continue to clash over proposals for a loss-and-damage finance facility, the Glasgow dialogue, established at COP26 in 2021, is now providing a space for countries and experts to “discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimise and address loss and damage”.

The dialogue, which began in June 2022, was viewed as a compromise after developing countries called for a new loss-and-damage finance facility at COP26. Small-island nations made it clear that they wanted the dialogue to culminate in such a facility being established.

Loss-and-damage discussions have always been tied up with money. This is because the costs associated with extreme weather and rising sea levels are enormous.

One widely cited study estimates that by 2030, developing countries are likely to face $290-580bn in annual “residual damages” – that is, damages from climate change that cannot be prevented with adaptation measures. (The range reflects low- and high-emission pathways RCP4.5 and RCP6). Other estimates have been within a similar range.

By 2050, the economic costs of loss and damage could exceed $1tn every year, as the impacts of climate change intensify.

(The IPCC notes that these estimates remain “highly speculative” given the lack of clarity about what constitutes “loss and damage”. See: Why is there controversy around the term ‘loss and damage’?)

For now, finance set aside specifically for loss and damage is essentially non-existent.

Scotland and the Belgian region of Wallonia pledged roughly $3m during COP26 in 2021, and Denmark has subsequently become the first UN member state to do so, committing around $13m.

Developing countries have made it clear they want a loss-and-damage finance “facility” to get funds flowing. These nations and their climate-activist allies tend to emphasise the need for reliable, grant-based support drawn directly from the wealth of developed countries.

In contrast, an idea frequently backed by developed countries is to address the problem using insurance schemes – for example, insuring homes against hurricane damage. This could shift some of the costs into the private sector.

The first-ever – unsuccessful – request for loss-and-damage finance, made by small-island states in 1991, was described as an insurance facility. However, in practice, their concept was more of a compensation fund, paid into by industrialised countries.

Most of the financing options that have been put forward by the executive committee of the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) have focused on insurance. (See: How is loss and damage being tackled at UN climate talks?)

However, large gaps in coverage make insurance an imperfect solution for loss and damage, with studies suggesting poorer countries benefit less.

Carbon Brief analysis of EM-DAT data suggests that, between 1990 and 2022, the economic damages from extreme weather events covered by insurance companies were 19 times higher in developed countries than developing countries.

There have been efforts to amend this, including initiatives such as the InsuResilience Global Partnership, a UNFCCC scheme that was set up to facilitate “climate-risk insurance for an additional 400 million poor and vulnerable people by 2020”. More recently, Germany and the rest of the G7 have put forward a proposal for a "global shield against climate risks".

However, contributions by developed countries to insurance schemes have been sporadic, meaning most costs are being borne by people in developing nations that can ill afford them. In its most recent NDC, for example, the Caribbean nation of St Lucia indicated that these kinds of schemes “may lead to a rise in costs beyond the capacity of the national budget”.

Furthermore, climate impacts are not easy to insure against, Dr Linnéa Nordlander, a law researcher at the University of Copenhagen, tells Carbon Brief:

“Insurance is based on profit and the possibility to profit from the policy holders, and that's not going to be possible when there is a guaranteed outcome of loss, [for events] that we know are only going to increase in frequency and severity.”

Further complications arise from attempts to insure against slow-onset events such as sea-level rise, although mechanisms have been proposed.

Aside from focusing on insurance, developed countries have made it clear that, in their view, loss-and-damage finance should remain rooted in existing finance streams, such as adaptation finance and humanitarian aid, rather than creating new pots of money.

Developing countries and climate-justice activists disagree, emphasising that funding must be “new and additional” – rather than rebranding existing funds.

Funding for adaptation and natural disasters is already insufficient and, therefore, would require an overhaul to meet the additional needs of loss and damage.

Developed countries pledged to mobilise $100bn in climate finance by 2020 and have failed to do so. They have been particularly unsuccessful at mobilising adaptation finance, which is meant to make up half of the total but as of 2020 was just one-third – $28.6bn.

Such funds may also be unsuitable for dealing with the immediate aftermath of extreme weather events. A quarter of the projects in the UN’s flagship Green Climate Fund (GCF) explicitly refer to loss and damage, but there is generally a year-long wait to receive GCF funding.

Meanwhile, analysis by Oxfam found that, on average for the period 2019-2021, UN humanitarian appeals linked to extreme weather were also underfunded and received $10bn each year.

These figures can be compared with the already-mentioned projections of loss and damage costs in 2030 of $290-580bn for developing countries.

With existing finance looking inadequate against future cost estimates, researchers and civil society groups have proposed various innovative new funding streams over the years.

Taxes or levies applied to fossil fuel companies, flights and shipping fuels have all been proposed, as has a worldwide system of carbon pricing that channels funds into some kind of loss and damage facility.

A financial transaction tax – a small levy placed on monetary transactions or trades of financial instruments – has also been suggested, with the burden falling on banks and traders. A tax on the super-rich is another proposed measure, with Oxfam estimating a 99% one-off billionaire tax on the top 10 richest people could raise $812bn.

All of these measures are designed to target wealthy, high-emitting individuals and companies, rather than the poor and vulnerable people currently bearing many of the costs of loss and damage.

As the chart shows, rough estimates suggest that a combination of them could cover a significant chunk of estimated annual loss-and-damage costs.

However, they all come with considerable political, social and technical issues.

Establishing a global carbon pricing system or tax on fossil-fuel companies – and then ensuring the funds were channelled into financing loss and damage – would likely face strong resistance, including from the many developing countries that rely heavily on fossil fuels.

A levy on flights, while already proven to work in some circumstances and relatively easy to govern, could harm the populations it is trying to help, given the reliance of many small-island nations on tourism. The same is true of shipping, another major contributor to island economies.

Dr Stacy-ann Robinson, who researches adaptation and small-island states at Colby College in Maine, says that any one of these approaches would likely be just a “drop in the bucket”:

“When you compare it to the potential needs of loss and damage…it kind of feels like none of those things in isolation would be enough. It would have to be lots of things all at once.”

Moreover, as the costs of loss and damage are projected to continue increasing, the streams of finance would need to increase further as well.

Developed countries pledged to mobilise $100bn in climate finance by 2020 and have failed to do so. They have been particularly unsuccessful at mobilising adaptation finance, which is meant to make up half of the total but as of 2020 was just one-third – $28.6bn.

Such funds may also be unsuitable for dealing with the immediate aftermath of extreme weather events. A quarter of the projects in the UN’s flagship Green Climate Fund (GCF) explicitly refer to loss and damage, but there is generally a year-long wait to receive GCF funding.

Meanwhile, analysis by Oxfam found that, on average for the period 2019-2021, UN humanitarian appeals linked to extreme weather were also underfunded and received $10bn each year.

These figures can be compared with the already-mentioned projections of loss and damage costs in 2030 of $290-580bn for developing countries.

With existing finance looking inadequate against future cost estimates, researchers and civil society groups have proposed various innovative new funding streams over the years.

Taxes or levies applied to fossil fuel companies, flights and shipping fuels have all been proposed, as has a worldwide system of carbon pricing that channels funds into some kind of loss and damage facility.

A financial transaction tax – a small levy placed on monetary transactions or trades of financial instruments – has also been suggested, with the burden falling on banks and traders. A tax on the super-rich is another proposed measure, with Oxfam estimating a 99% one-off billionaire tax on the top 10 richest people could raise $812bn.

All of these measures are designed to target wealthy, high-emitting individuals and companies, rather than the poor and vulnerable people currently bearing many of the costs of loss and damage.

As the chart shows, rough estimates suggest that a combination of them could cover a significant chunk of estimated annual loss-and-damage costs.

However, they all come with considerable political, social and technical issues.

Establishing a global carbon pricing system or tax on fossil-fuel companies – and then ensuring the funds were channelled into financing loss and damage – would likely face strong resistance, including from the many developing countries that rely heavily on fossil fuels.

A levy on flights, while already proven to work in some circumstances and relatively easy to govern, could harm the populations it is trying to help, given the reliance of many small-island nations on tourism. The same is true of shipping, another major contributor to island economies.

Dr Stacy-ann Robinson, who researches adaptation and small-island states at Colby College in Maine, says that any one of these approaches would likely be just a “drop in the bucket”:

“When you compare it to the potential needs of loss and damage…it kind of feels like none of those things in isolation would be enough. It would have to be lots of things all at once.”

Moreover, as the costs of loss and damage are projected to continue increasing, the streams of finance would need to increase further as well.

Raising loss-and-damage finance can be viewed as part of a wider push to increase climate finance from “billions to trillions”.

Loss-and-damage advocates point to the massive mobilisation of funds in response to the Covid-19 pandemic as an example of what can be achieved.

Besides increased public spending by wealthy countries, this included measures such as “special drawing rights” (SDRs). SDRs are issued by the International Monetary Fund as reserve assets that countries in need can swap for hard currencies when required.

Redirecting fossil fuel subsidies – which are estimated to cost billions or even trillions each year, depending on how they are defined – has also been suggested as a source of funding by NGOs. UN secretary-general António Guterres has proposed a windfall tax on the excess profits of oil-and-gas companies during the energy crisis as an additional source of money.

Amid devastating flooding in Pakistan in 2022, there have also been renewed calls for the cancellation of debts for developing countries. However, Lidy Nacpil of the Asian Peoples Movement on Debt & Development (APMDD) tells Carbon Brief such measures, while welcome, “should not be counted towards climate finance that is also urgently needed for loss and damage”.

Historically, developed countries have resisted loss-and-damage finance because of its ties to liability and compensation, but when the Paris Agreement emerged in 2015, the US in particular ensured that the decision text stated clearly that these issues were not connected.

While legal scholars have suggested that compensation is still not entirely off the table, in practice, experts tell Carbon Brief that developing countries have largely begun calling for money on the basis of solidarity – as the impacts of climate change become more apparent.

Just as each disaster is different, loss-and-damage impacts can be extremely localised. The needs of countries and communities are therefore varied, with the means to address these needs via climate finance complex and best determined with local knowledge.

Experts tell Carbon Brief that loss-and-damage spending needs to be divided roughly into three categories: relief and rehabilitation; recovery and reconstruction; and disaster risk reduction.

These broadly align with the categories set out by the UN’s Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, which groups aid spending into emergency response, reconstruction, and prevention and preparedness.

According to Ashfaq Khalfan, director of climate justice at Oxfam America, loss-and-damage finance needs to be spent on “effectively anything that is not about preventing climate harms, but rather about rebuilding”.

This would, he says, cover technical assistance, as well as funds for emergency relief and rebuilding. It would offer support to restore or provide alternative livelihoods, emergency cash transfers and social support, restoring ecosystems, psychological support and capacity-building.

Loss-and-damage finance would also fund needs such as migration and relocation of the permanently displaced, social protection and other safety nets, as well as building alternative livelihoods – for example, when farming is no longer a viable option due to salinisation of soil. Khalfan adds:

“For non-economic losses, activities such as active remembrance of areas or things lost to climate change, counselling services and formal apologies are possible actions to address.”

Some of the potential areas that could be addressed with loss-and-damage finance are outlined in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, as potential “areas of cooperation and facilitation to enhance understanding, action and support”.

These include early-warning systems, emergency preparedness, risk insurance facilities and measures that support the resilience of communities and ecosystems confronted with loss and damage.

Some countries and regional coalitions have spelled out their individual, collective and contextual needs in submissions to the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM), the oversight body on loss and damage under the UNFCCC.

These submissions are an opportunity for countries to say what specific measures and funding they need, in order to recover from loss and damage.

The island nation of Vanuatu, for instance, suggests finance for a range of different economic and non-economic losses in its submission to the WIM.

These include needs such as:

Some of these issues are captured in Vanuatu’s recently updated NDC, which has been welcomed due to its comprehensive breakdown of loss and damage needs. The majority of its stated needs would go towards improving its capacity to “assess and redress” climate impacts, as the chart below shows.

Vanuatu is part of AOSIS, which has also made a collective submission to the WIM that identifies three action areas, “each of which requires a level of financial support that is currently well beyond the capacity of small-island developing states, either individually or collectively”.

Means to address permanent loss – from which recovery or rehabilitation is not possible – and impacts from slow-onset events and their political, social and economic implications have not been analysed or prepared for enough, according to AOSIS nations.

They highlight “the need for SIDS and other particularly vulnerable countries to have effective legal, financial and institutional measures in place to protect people displaced by the impacts of climate change”.

According to loss-and-damage expert Harjeet Singh of Climate Action Network (CAN), “relocation is going to be a massive part of loss and damage going forward”, as well as post-disaster psycho-social care. He tells Carbon Brief:

“This is why we need to start looking at the impacts of slow-onset events that the traditional humanitarian community has not been aware of: sea level rise, ocean acidification, loss of biodiversity, glacier melt. The scale of relocation is going to be much more, because people are going to be displaced either because of excessive heat or desertification or rising seas or coastal erosion. Millions of people are going to lose their homes, but what do we do, because there is currently no policy to accommodate them? This is where the whole loss-and-damage mechanism or funding becomes really important.”

Investment in early warning systems is also a high priority for many countries, according to their WIM submissions analysed by Carbon Brief. Early warning systems can broadly be described as integrated communication and forecasting systems to help policy-makers and communities plan and respond to climate-related extreme weather events.

An effective early-warning system has four components: tools to measure risks better; a monitoring and warning service that can make accurate predictions; communication systems to get the word out to governments and vulnerable communities; and their ability to respond to loss and damage.

While many of these needs have been spelled out in the Paris Agreement – and by affected countries – sufficient climate finance is still not forthcoming.

Flows of finance from developed to developing countries for loss and damage are currently limited to aid, either in the form of development or humanitarian finance or insurance.

Aid is governed by humanitarian considerations, some international obligations, and is mostly voluntary, although self-interest and “overt geopolitics” play a role in who gets what.

For the most part, countries that cause harm are not responsible for paying commensurate damages in an aid context. Humanitarian principles imply a degree of separation between those that cause harm and those that participate in the response.

This is a marked difference to how many developing countries and climate-justice campaigners have framed loss and damage, where high-polluting nations that historically and currently contribute to climate change must provide support to address its impacts.

According to a 2022 report by the World Resources Institute that looked at OECD data on official development assistance, $133bn – or 11% – of international aid was disaster-related from 2010-2019. This amount includes non-climate related events such as earthquakes.

Of this, 90.1% was earmarked for emergency response, 5.8% for reconstruction relief and rehabilitation, and 4.1% was earmarked for disaster prevention and preparedness. The report points to Official Development Assistance (ODA) being an important source of loss and damage finance.

However, both ODA and international finance institutions determine eligibility for aid or concessional financing based on countries’ income categorisation, such as per-capita GDP or Gross National Income (GNI).

Many small island states, for instance, are considered – or will soon qualify – as high-income, developed countries that are not eligible for ODA, even though they are considered eligible for international climate finance.

Many countries that have been battered by storms and seas alike are also in deep debt distress, having to cut spending on climate to qualify for more concessional financial support.

In a 2021 report, UN Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) observed that “overall disaster-related ODA for prevention and preparedness may not be tailored according to needs”.

The report found that, while there is a clear association between mortality levels and international aid towards emergency response, countries with high death tolls, with a few exceptions, receive scant funding for prevention and preparedness.

According to the UNDRR, this type of funding is particularly important in the case of climate change, where events can grow in intensity and frequency, inflicting heavy economic damages on the same places repeatedly.

Investing in risk reduction “enhances the efficiency of development aid and national investments, as it prevents or mitigates future losses”, the UNDRR says. It estimates “every $1 invested in risk reduction and prevention can save up to $15 in post-disaster recovery”.

When it was established at COP25 in Madrid, the Santiago Network was pitched as a body that would “catalyse the technical assistance”, bringing together organisations – including aid groups – and experts to help implement approaches to “avert, minimise and address” loss and damage in developing countries.

However, so far, the network is little more than a website.

Countries were invited to make submissions to the website portal by 15 March 2022, but these were to focus on discussing how the network would work, its structure and operations, not actual requests for technical assistance.

In August 2020, the network had asked developing countries to participate in a survey towards mapping “potential needs for relevant technical assistance”.

While 14 countries submitted their needs statements – ranging from “establishing a baseline on non-economic and social loss and damage” through to “designing proposals and access to financing for climate information services and early warning systems” – what has happened since is still unclear.

The term may appear self-explanatory, but the question of what constitutes “loss and damage” resulting from climate change has been highly politicised and contentious.

As one 2021 paper put it, “loss-and-damage debates have been mired by lack of definition”, subject to different interpretations both in UN negotiating halls and the scientific literature.

Small-island states, developing countries and climate-justice groups have traditionally framed loss and damage as a way to hold big historical emitters to account for causing climate change. This often involves highlighting the existential threat posed by climate change and demanding compensation from nations in North America and Europe.

This has led to loss-and-damage finance being colloquially referred to by some activists and journalists as “climate reparations” – a politically charged term that recalls demands made by the descendents of African slaves in the US and the Caribbean.

Such a framing is untenable for many developed countries. Governments fear being held liable for trillions of dollars, even as they struggle to meet their existing climate-finance commitments and face various domestic pressures.

Instead, these nations – most prominently the US – have tried to keep loss and damage within discussions around adaptation. This approach often involves framing all climate impacts as “loss and damage”, meaning the topic is already well covered by efforts to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts.

Even after years of discussions, negotiators from wealthy countries can still be seen pushing back against the notion of loss and damage as a distinct issue.

Scientific research has reflected the diversity of opinions about loss and damage. The most recent IPCC report identified a “coalescence” around a handful of relevant topics, including “risk management, limits to adaptation, existential risk, finance and support including liability, compensation and litigation”.

The most widely accepted definition of loss and damage in the literature involves dealing with climate risks that remain despite efforts to cut emissions and adapt to the consequences. This definition supports the developing countries’ “beyond adaptation” framing, without resting on the need for compensation from the rich.

Despite this apparent clarity, former EU and AOSIS negotiator Kaveh Guilanpour, of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, tells Carbon Brief that the continued confusion around loss and damage is understandable:

“It is very difficult, except at the extremes, to understand where adaptation ends and where loss and damage starts.”

In a 2016 paper, Prof Lisa Vanhala of University College London (UCL) and Cecilie Hestbaek from humanitarian charity Elrha characterised the term itself as a political compromise.

They argue that since the Bali Action Plan in 2007, which included the term “loss and damage” for the first time in a negotiated UN text, it has entered common usage as a catch-all phrase that does not require parties to agree on a definition.

Such “constructive ambiguity” – a term credited to controversial Cold War-era US diplomat Henry Kissinger – is common in UN climate talks, with texts often left vague to enable diverse countries to come to an agreement.

Carbon Brief’s analysis of Earth Negotiations Bulletin reports, which track UN climate negotiations in detail, shows how references to “loss and damage” have shot up since 2007, far exceeding mentions of “insurance”, “liability” and “compensation”.

This could reflect the rising profile of loss and damage, as well as the successful effort by the US to exclude compensation for loss and damage from the Paris Agreement in 2015.

Negotiators tell Carbon Brief they feel constructive ambiguity has allowed considerable progress in discussions of loss and damage, including the formation of key institutions such as the WIM.

However, veteran Philippines climate negotiator and Greenpeace East Asia executive director Yeb Saño says that while this approach has “saved this [UN] process many times…ambiguity will not avert the climate crisis”.

Vanhala tells Carbon Brief that she agrees there are limits to this approach:

“I'm beginning to understand the destructive potential of this idea and what it's doing, and the battles that need to continually be refought even after an agreement is reached at the global level.”

One issue often raised by developed countries has been that developing countries have not been clear about what they need. Indeed, there is evidence that when loss and damage has been included in national policy-making it has been conflated with adaptation.

However, loss and damage is increasingly being accounted for in national climate strategies, making its parameters easier to define.

Analysis by Carbon Brief of national government policy documents available in English from the Climate Policy Radar database indicates a particular surge in the use of the term “loss and damage” since the Paris Agreement in 2015.

Analysis ahead of COP26 showed that one-third of climate plans submitted under the Paris Agreement specifically referenced loss and damage, more than half of which came from small-island states. No developed country plans mentioned loss and damage.

Dr Elisa Calliari, one of the study authors and part of the Politics of Climate Change Loss and Damage (CCLAD) project at UCL, tells Carbon Brief:

“Some countries seem to be actively shaping the loss and damage concept by putting forward certain understandings which relate to specific challenges they face at the national level.”

Finally, the politics of loss-and-damage language have also spilled over into the world of the IPCC.

While the IPCC has covered relevant issues, such as flood damage from sea level rise, since its first report in 1990, it has only begun using the term “loss and damage” over the past decade. The topic was analysed in depth for the first time in 2018 for the special report on 1.5C.

At the same time, there has also been a growing use of the term “losses and damages”, a more politically neutral term for the damages caused by climate change.

While the IPCC reports themselves are scientific documents, the summaries for policymakers (SPMs) that accompany them must be agreed by governments.

“As the term ‘loss and damage’ carries political baggage, it has not made it into any approved SPM to date,” Friederike Hartz, a geography PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge and research assistant at UCL’s CCLAD project, tells Carbon Brief.

Finally, the politics of loss-and-damage language have also spilled over into the world of the IPCC.

While the IPCC has covered relevant issues, such as flood damage from sea level rise, since its first report in 1990, it has only begun using the term “loss and damage” over the past decade. The topic was analysed in depth for the first time in 2018 for the special report on 1.5C.

At the same time, there has also been a growing use of the term “losses and damages”, a more politically neutral term for the damages caused by climate change.

While the IPCC reports themselves are scientific documents, the summaries for policymakers (SPMs) that accompany them must be agreed by governments.

“As the term ‘loss and damage’ carries political baggage, it has not made it into any approved SPM to date,” Friederike Hartz, a geography PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge and research assistant at UCL’s CCLAD project, tells Carbon Brief.

It is notable that, despite this, “losses and damages” was mentioned 15 times in the most recent SPM, published in early 2022.

Hartz says that, in her view, the latest IPCC glossary, which makes a distinction between the political (capitalised “Loss and Damage”) and scientific (“losses and damages”) approaches to the subject, allowed this progress to take place. She adds that the political implications of this development remain to be seen.