Pakistan is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change in the world. It is currently in the midst of a crippling energy and economic crisis that has brought it to the brink of bankruptcy.

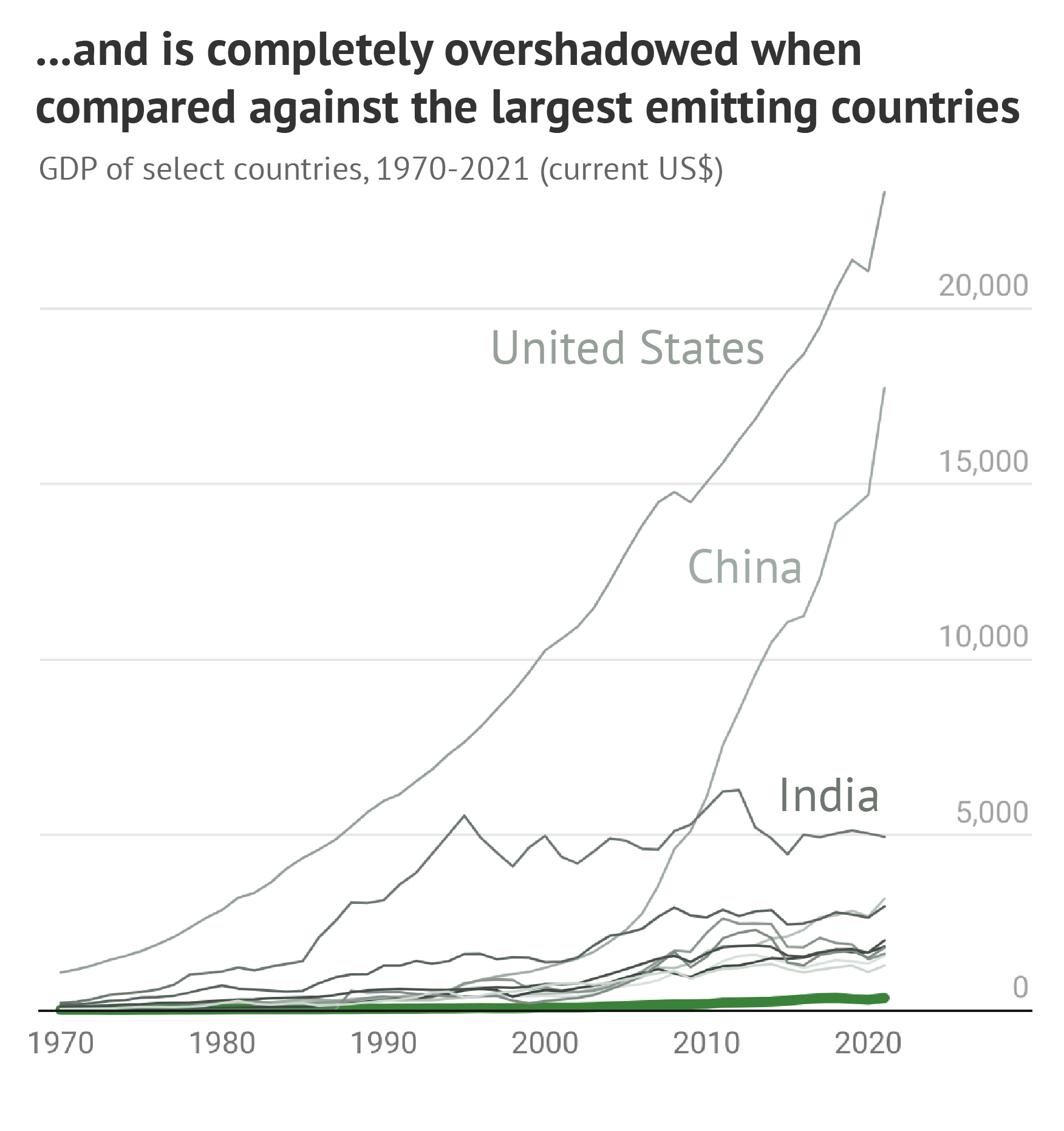

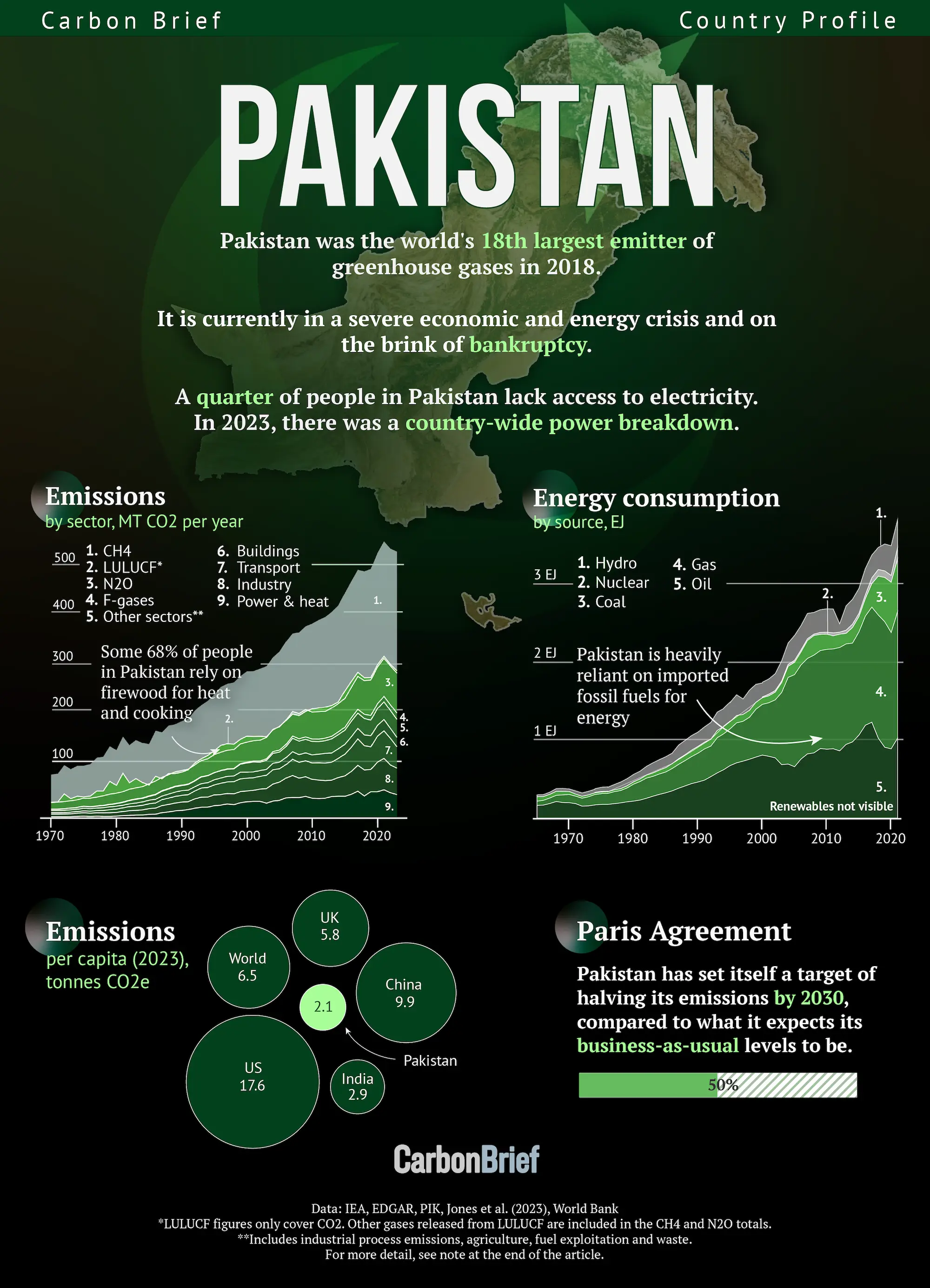

The country, which is the fifth most populous in the world and home to more than 230 million people, was the 18th largest emitter of greenhouse gases in 2018.

Its current crisis is closely tied to its dependency on fossil-fuel imports, particularly in light of global price hikes driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Imported fuels currently make up 40% of the country’s primary energy supply.

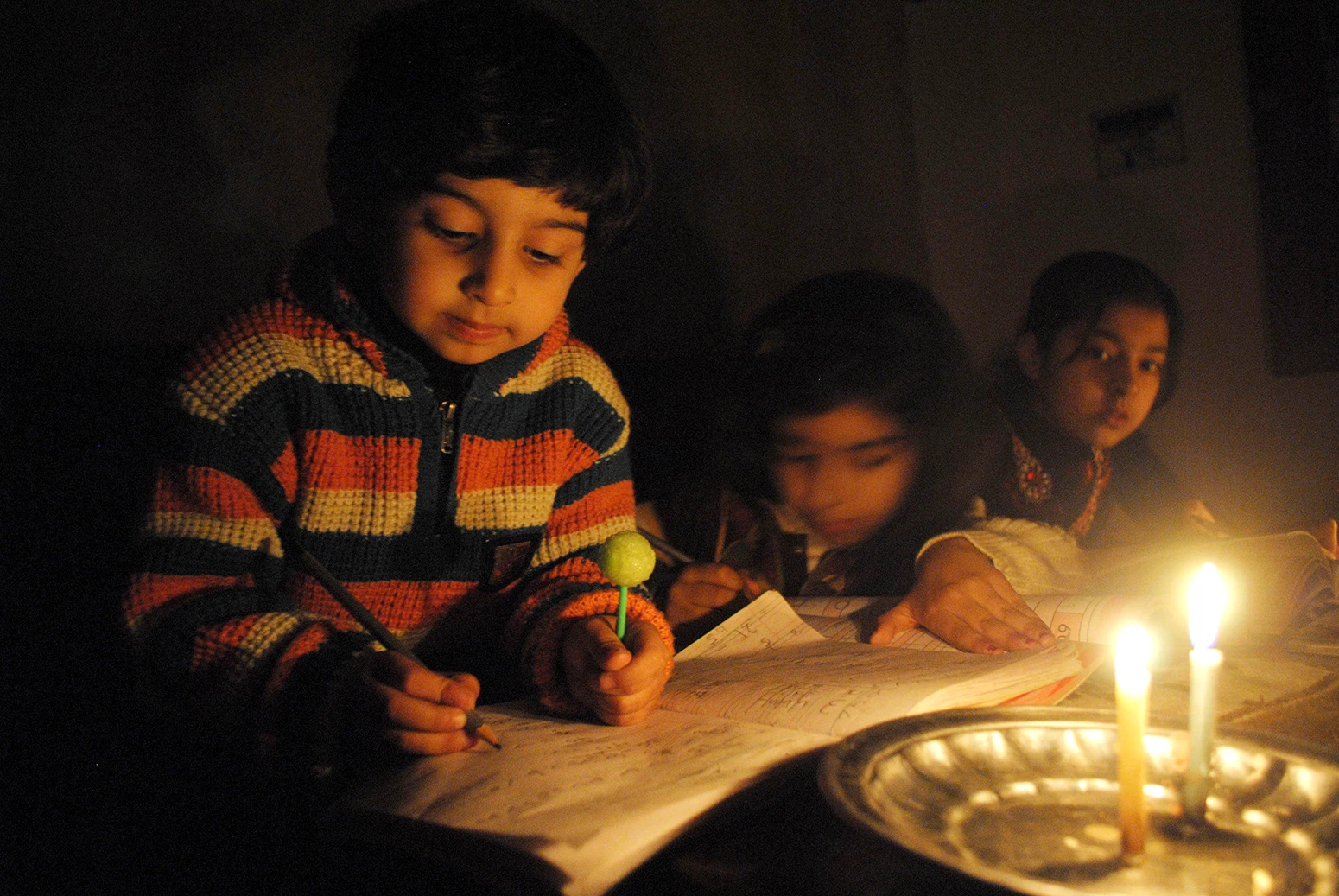

One in four people in Pakistan lack access to electricity. In January 2023, the country faced a complete power breakdown, which lasted for 24 hours in some areas.

Pakistan in 2020 committed to a moratorium on building coal-fired power plants. However, the government in 2023 promised to quadruple power plants fuelled with domestic coal to meet energy needs without relying on imports. Coal mining in the country has been linked to fatal disasters, slavery and child abuse.

Carbon Brief Country Profiles

Select a country from the series

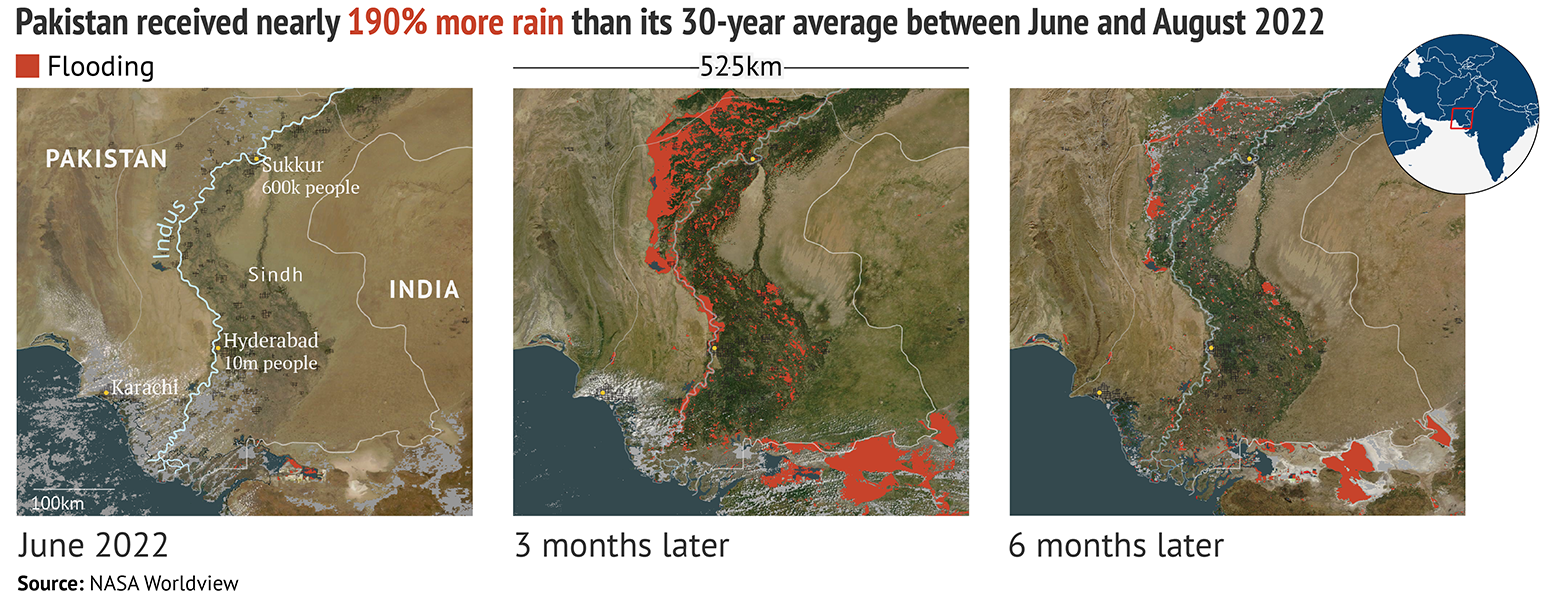

More than 1,700 people died in Pakistan’s 2022 floods, which were fuelled by rains made 75% more intense by climate change. Many displaced by the floods remain homeless in 2023.

The devastating impact of the floods buoyed Pakistan’s call for a loss-and-damage fund to be established at the COP27 climate summit in 2022.

Pakistan has set itself a “cumulative conditional target” of limiting emissions to 50% of what it expects its business-as-usual levels to be in 2030. It says that 15% will be met by its own resources and 35% is subject to international financial support.

Politics

Pakistan was established in 1947 following the end of 200 years of British colonial rule over the Indian subcontinent. At this time, the UK divided the subcontinent into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

It is now the world’s fifth-most populous country and the second-largest Muslim population after Indonesia. It is also the second-largest country in South Asia by area.

Pakistan is ethnically and linguistically diverse. The national language of Pakistan is Urdu, which is also the official language along with English. Other languages spoken in Pakistan include Punjabi, Saraiki, Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, Brahvi, Hindko, Kashmiri, Shina, Balti and further local languages.

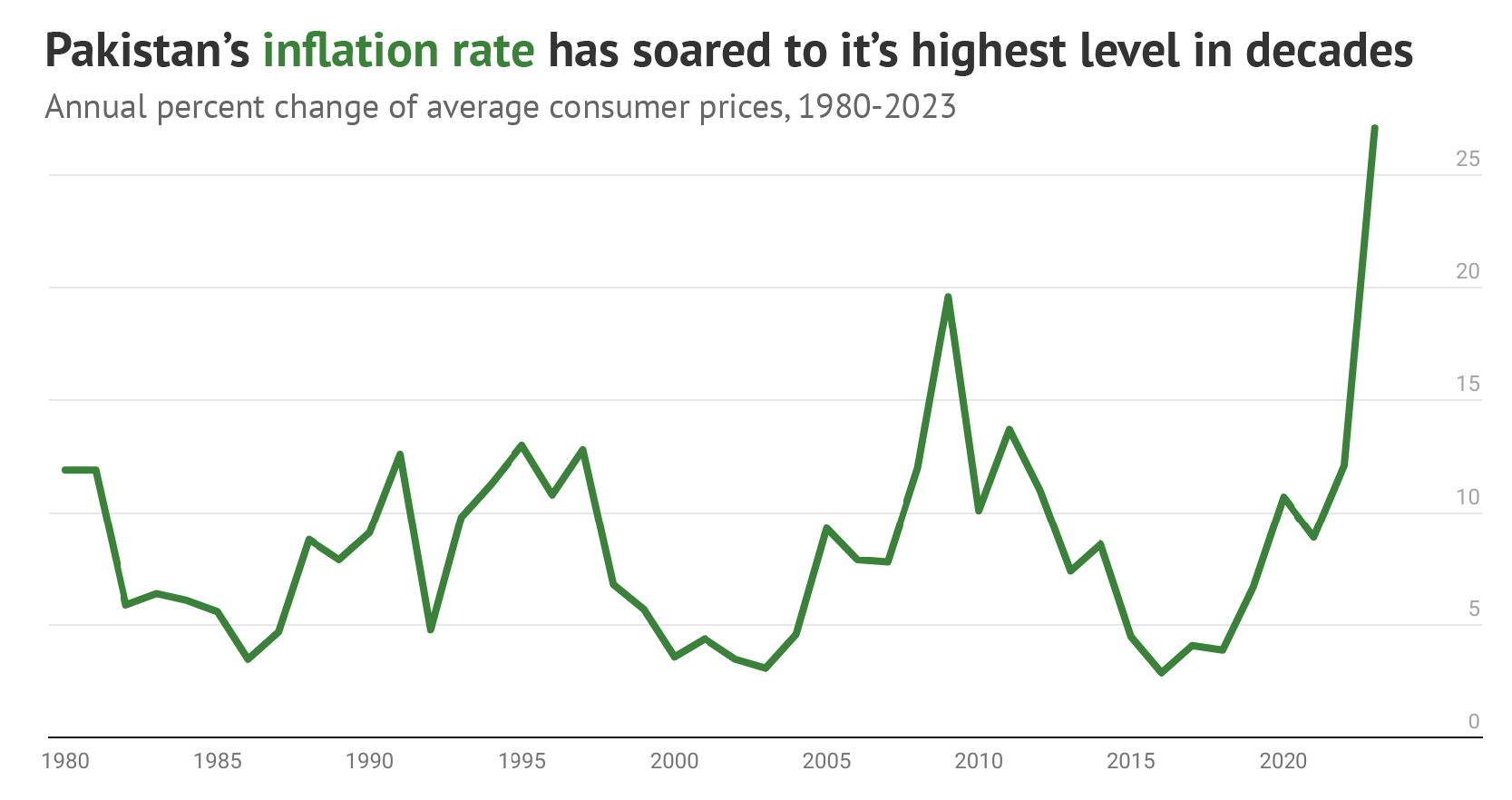

Pakistan is currently facing a severe economic crisis. An editorial focused on the crisis in the Financial Times said that the country’s foreign exchange reserves dropped to just $3.7bn in late January 2023, equivalent to just three weeks of imports. The FT added:

“As it is, Pakistan risks following Sri Lanka into default, where food and medicine have been in short supply. But with a population 10 times that of Sri Lanka, a nuclear arsenal, a military with a history of meddling, and extremist Islamists who are displaying their bloodthirsty fanaticism once more, default is a situation international creditors and multilateral institutions must help Pakistan avoid.”

The Indian newspaper Mint reported that the country’s external debt rose by a sharp 38% to $73bn by the end of January, when compared to the year before. Al Jazeera reported that inflation in the country surged to 31.5% in February, the highest level since 1974.

As of 2018, 40% of Pakistan’s population lived in poverty. The current figure is likely to be higher following the onset of the Covid pandemic and a cost-of-living crisis fuelled by sky-high energy prices and inflation.

Energy is right at the heart of Pakistan’s ongoing economic crisis.

Pakistan’s power sector is plagued by a large circular debt, a type of public debt that has built up due to the cascading impact of unpaid government subsidies on power distributors and producers, as well as deep structural issues in the sector.

The country is heavily reliant on importing fossil fuels, which currently make up 40% of Pakistan’s primary energy supply.

Pakistan also suffers from chronic energy access issues, with one in four people lacking access to electricity in 2020.

Children study in candle light during a power cut in northwest Pakistan's Peshawar, January 2015. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

All of these factors left Pakistan highly vulnerable to the global energy price hike spurred by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In June 2022, Pakistan’s petroleum minister told journalists that the country was struggling to secure supplies of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as it was being outbid by European countries looking to source fuels away from Russia.

According to Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper, minister Musadik Malik said:

“We don’t have enough energy right now. The gas is not available and we can’t afford such expensive gas. So what we are doing is arranging alternates. The recent increase in production, imports of coal and furnace oil is part of the same strategy.”

In January 2023, the country faced a complete power breakdown due to a technical fault while undertaking energy-saving measures, which lasted for 24 hours in some areas.

In February, energy minister Khurram Dastgir Khan said lack of access to LNG was forcing the country to return to coal and promised to “quadruple” domestically fuelled coal power capacity in response to the crisis, according to Reuters. (See coal, oil and gas for more information.)

The government is currently in talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to secure a $6.5bn loan in order to avoid a default. It has already taken “tough measures” in a bid to secure the loan, including increasing energy prices and taxes amid its cost-of-living crisis, Bloomberg reported.

(Pakistan has received 22 loans from the IMF in the past 60 years, according to the Pakistan Tribune.)

The energy and economic crisis is heightened still further by political instability.

Former cricket star Imran Khan swept to power in 2018 with the populist party he founded, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party. But he was ousted in April 2022 after becoming the first prime minister to lose a no-confidence vote in parliament. His removal led to widespread protests.

Supporters of Pakistan Terhreek-e-Insaf take part in a protest march in Wazirabad, Pakistan, 10 November 2022. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

Shehbaz Sharif of the centre-right Pakistan Muslim League (N) party was elected as the replacement a few days later, causing tension with Khan’s remaining supporters in parliament. Sharif’s party is a member of the Pakistan Democratic Movement, an alliance of more than a dozen political parties that opposed Khan’s leadership.

In May 2023, Khan was arrested by Pakistan’s anti-corruption bureau, leading to deadly violence nationwide. His arrest was ruled illegal by Pakistan’s Supreme Court a few days later.

Later this year, Pakistan will hold general elections. They are due to take place no later than 60 days after the dissolution of the National Assembly in August, meaning they should take place before the end of October.

A poll of 2,000 people conducted by Gallup Pakistan in March 2023 found widespread support for Khan, with his approval rating jumping to 61% in February, up from 36% in January last year. Sharif’s popularity stood at 32% in February, dropping from 51% last year.

Both Khan and Sharif have spoken passionately about the impact of climate change on Pakistan – and the need for historic large emitters such as the US and UK to pay for their pollution.

Muhammad Shehbaz Sharif, prime minister of Pakistan, speaks at COP27 on 8 November 2022. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

While in power, Khan set out a number of policies on transitioning to renewable power and using “nature-based solutions” to tackle climate change (discussed in more detail below).

In 2015, a decision was made to reinstate Pakistan’s climate change division as a ministry. Current climate minister Sherry Rehman has been a vocal force for climate justice at UN talks. (See: Paris pledge.)

Paris pledge

Pakistan is part of three negotiating blocs at international climate talks, including the G77 plus China, the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) and the Coalition for Rainforest Nations (CfRN). (More information on each group is available in Carbon Brief’s in-depth explainer of negotiating blocs.)

At COP27 in Egypt in 2022, Pakistan chaired the G77 plus China negotiating group – representing more than 130 nations – and was instrumental in the agreement of a specific fund for loss and damage. (Loss and damage is a term used for the suffering already caused by climate change, see Carbon Brief’s full explainer for more information.)

Pakistan’s position as chair came just months after floods, fuelled by rains made 75% more intense by climate change, devastated the country. In her closing remarks to the conference, Pakistan’s climate minister Sherry Rehman said the fund represented a “down payment in our joined futures and investment in our coming generations”.

Sherry Rehman, minister of climate change for Pakistan, at COP27 on 17 November 2022. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

Pakistan is signed up to the Paris Agreement, the international deal aimed at tackling climate change. It ratified the agreement in 2016.

The country’s greenhouse gas emissions were 529.1m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2023 – making it the world’s 18th largest emitter, according to a database published in Scientific Data by Dr Matthew Jones of the University of East Anglia and collaborators. This includes emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF).

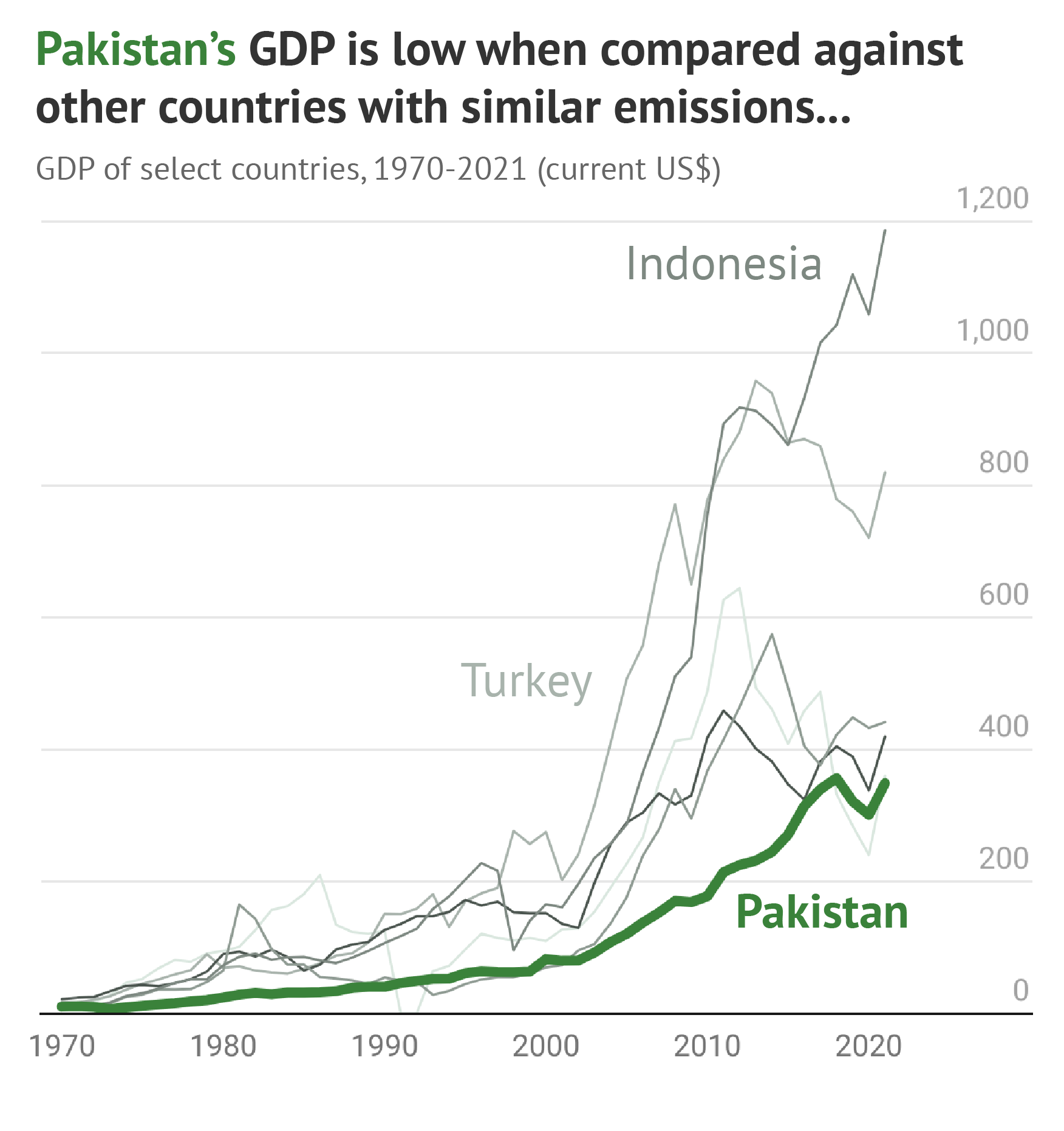

That year, its emissions per person (“per-capita emissions”) were just 2.1 tonnes of CO2e, much lower than the global average of 6.7.

It submitted its first climate pledge under the Paris Agreement – known as its “nationally determined contribution (NDC) – in 2016. In this, Pakistan said it would cut its emissions by up to 20% by 2030, when compared to its projections for business as usual. However, this level of emissions cuts was contingent on the country receiving $40bn in investment from developed countries by 2030.

Pakistan updated its climate pledge in 2021, to set a “cumulative conditional target” of limiting emissions to 50% of what it expects its business-as-usual levels to be in 2030. (Under a business-as-usual scenario, Pakistan expects its annual emissions to reach 1.6bn MtCO2e by 2030. If it meets its climate targets, its emissions will instead grow to 801 MtCO2e.)

Pakistan says that 15% of its efforts to tackle emissions will be met by its own resources and 35% is subject to receiving $101bn in financial support from developed countries by 2030.

The country has not yet made a public pledge to reach net-zero emissions. On the sidelines of the COP26 climate summit, the climate aide of the former prime minister Imran Khan told the Third Pole that Pakistan “doesn’t believe in the net-zero concept at the moment”.

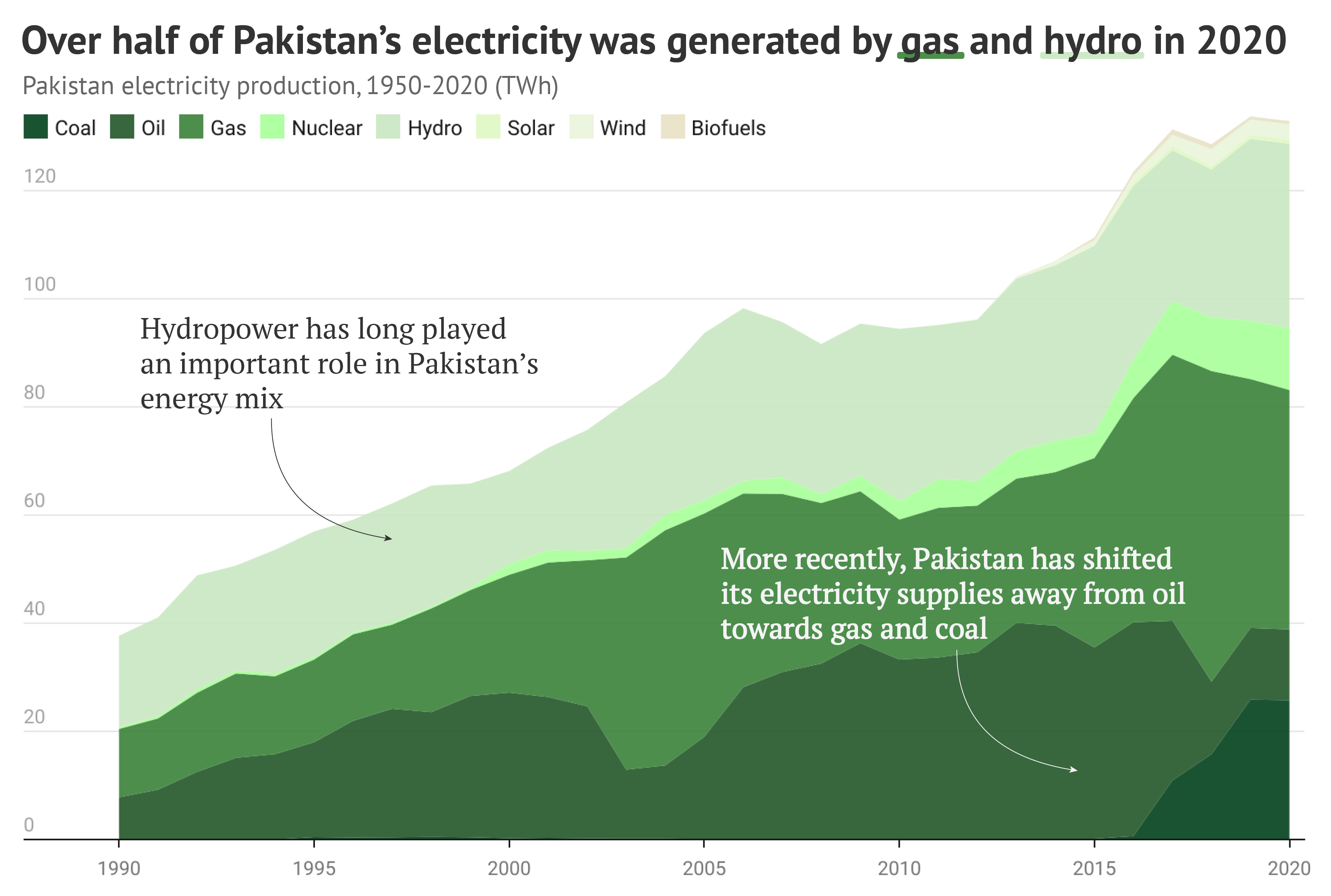

Oil, gas and coal

Fossil fuels have long dominated Pakistan’s energy supplies. In 2021, gas (42%), oil (27%) and coal (17%) accounted for a combined 86% of the country’s energy needs, with renewables (10%, mainly hydro) and nuclear (4%) making up the rest (see graphic and sections below).

There is a long history of fossil fuel extraction in Pakistan.

Exploration for oil in Pakistan began in the late 19th century, fuelled by a need to power a railway system being built to secure the Indo-Afghan border.

The country’s first gas field was discovered in Balochistan in 1952, near the Sui gas field, which remains the country’s biggest gas discovery to date.

Along with oil and gas, coal was also discovered in Balochistan in the late 19th century and mined to serve colonial railways under the British regime.

Today, domestic oil production accounts for just 16% of demand. Likewise, while domestic gas production has grown 10-fold since 1970 it has nevertheless failed to keep up with demand.

As a result, gas imports have been growing rapidly and have doubled since the first liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal was built in 2015.

The country’s dependency on imported fossil fuels is a well recognised problem that has constrained growth and kept energy and electricity prices steep.

Pakistan’s coal deposits are concentrated in the provinces of Sindh, Punjab and Balochistan, with total reserves estimated at 185bn tonnes. Sindh is host to two major coalfields: the Lakhra coalfield and the Thar coalfield in the Thar desert bordering India, the latter containing one of the world’s largest lignite deposits. Lignite is the most polluting form of coal.

Coal production in Pakistan is currently plagued by social, environmental and safety issues, as working conditions have not improved in decades. According to the Pakistan Central Mines Labour Federation (PCLMF), the country’s coal sector employs 100,000 workers in 400 coal mines, miners “usually start[ing] work at age 13” and “forced into unemployment” due to illnesses and injuries by the age of 30.

Child labour, bonded labour, deaths, explosions, modern slavery conditions and child sexual abuse are “rife” in Balochistan’s mines, where coal mining began in Pakistan, the Guardian reported in 2020. PCLMF estimates that between 100 and 200 labourers die on average in mine accidents every year, with 18 killed in May 2022 alone.

The coal rush in Thar, whose 175bn tonne coal reserves “exceed[s] the oil reserves of both Saudi Arabia and Iran”, is also taking a toll on Indigenous communities and desert ecosystems, Dawn reported earlier this year.

Thari nomads on camelback. Thar Desert, Pakistan. Credit: Neil Cooper / Alamy Stock Photo.

Civil society groups have pointed to land acquisition without consent for Thar’s expanding coal mines and torture of mine workers, Dawn reported, while environmental groups have warned of mining’s groundwater impacts in the desert region.

As a result of its limited low-carbon energy supplies and a failure to further expand domestic coal, oil and gas production, Pakistan remains heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels. The expense of sourcing these imports is one reason for the country’s chronic energy deficit.

In 2021, shortages in Europe coupled with high demand in Asia pushed spot LNG prices to record highs, forcing Pakistan to pay the most it ever has for shipments. The country has only two long-term LNG contracts with Qatar.

The next year, long-term gas suppliers cancelled their shipments coinciding with the surge in European gas prices brought on by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Pakistan issued another tender for long-term LNG supply starting in 2023. However, not a single bidder responded, leaving little spare supply until 2026, Bloomberg reported.

Furthermore, many of Pakistan’s transnational pipeline projects have been delayed: the country may face arbitration and an $18bn fine if it fails to finish work on the Iran-Pakistan (IP) gas pipeline.

Pakistan’s end-of-year energy plans in 2022 indicated that the country wants to bring down the share of imported coal and LNG to 8% and 2% by 2030, respectively, to serve energy security needs, support climate targets, avoid the high cost of imported fuels and supply challenges driven by the international market.

The cash-strapped country is also set to receive its first shipment of discounted Russian crude oil in Karachi in May, with Islamabad to target imports of 100,000 barrels per day “if the first transaction goes through smoothly”, Reuters reported.

The tension between securing adequate and affordable energy supplies to expand access, at the same time as meeting the country’s climate goals, has caused several shifts in Pakistan’s strategy.

Former prime minister Nawaz Sharif’s answer to rising energy bills and chronic powercuts was to boost domestic coal production and approve new coal power plants. Later, then-prime minister Imran Khan announced a moratorium on new coal power at the Climate Ambition Summit in 2020, convened to mark the fifth anniversary of the Paris agreement.

The Third Pole reported that this would not affect projects in the pipeline under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), instead only affecting two imported coal projects which “had already been scrapped because of an earlier moratorium on using imported coal”.

Soon after the country’s worst nation-wide blackout in January 2023, brought on by energy-saving measures gone wrong and old transmission equipment, the government of recently installed prime minister Shehbaz Sharif announced another shift, as inflation hit double-digit figures.

This includes a plan to cut imports and revive domestic energy production, in particular coal from the Thar coal fields, a decision sparking climate fears among some, but one that other energy commentators say is essential to ensure energy security first while Pakistan pivots to a “sustainable growth trajectory”.

In February 2023, Reuters reported that the country’s energy minister wanted to “quadruple domestic coal-fired capacity…and will not build new gas-fired plants”, which experts clarified to Carbon Brief would involve imported coal plants with spare capacity running on domestic coal.

In March 2023, Sharif formally inaugurated the new 1,320 megawatt Thar Coal Block-I Coal Electricity Integration project under CPEC, which would need 7.8m tonnes of domestically-mined coal a year, China’s Global Times reported.

Through these twists and turns, Pakistan has been shifting its electricity supplies away from expensive, imported oil towards coal and gas, as the chart below shows.

(Nuclear and, more recently, wind and solar, have also been expanding, see below.)

However, Pakistan’s increasing reliance on imported gas to generate electricity has been called into question during the global energy crisis, when prices surged to record highs.

According to thinktank Global Energy Monitor, Pakistan currently has 7.6 gigawatts (GW) of coal capacity – almost all of which has been built since 2015 – with another 4GW in its pipeline.

Pakistan has announced plans to revive long-stalled coal plants along the CPEC, raising “fresh questions” about China’s pledge to not build any new coal plants abroad, China Dialogue reported.

The country’s former chief economist Dr Pervez Tahir pointed out in the Express Tribune that “coal is all that Pakistan has to reduce dependence on an increasingly uncertain world”, but that it must “use modern technologies of mitigation”.

(Pakistan currently has extremely limited wind and solar capacity, see: Renewables including hydropower.)

Nuclear

Pakistan currently has six operating nuclear power plants. The total installed capacity is 3,530 megawatts (MW).

Five of these plants make use of Chinese technology and were financed by China. This includes three nuclear reactors in Pakistan’s Punjab province and two in Karachi.

The second of the Karachi reactors – a 1,100MW plant – connected to the grid in February 2023.

According to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, the two Karachi plants are part of the China-Pakistan economic corridor, a 3,000km infrastructure network project in Pakistan that is a major plank in China’s wider Belt and Road Initiative.

Karachi Nuclear Power Plant Unit-2 (K-2), Karachi, Pakistan. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

Nuclear power provided around 9% of Pakistan’s electricity in 2020, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). This rose to around 14% in 2022 with the opening of new plants, according to the thinktank Ember.

Back in 2017, Pakistan’s atomic energy commission chairman told Reuters that the country had plans to build a further two to three big reactors with the aim of achieving 8,800MW of nuclear power by 2030.

However, no further new reactors have been announced. Neither the country’s international climate pledge published in 2021 nor its Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy published in 2019 mention nuclear power.

Pakistan’s Dawn reported that, in February 2023, Rafael Grossi, head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), said that there was “strong political support for new nuclear power plants in Pakistan” during a visit to Islamabad.

Renewables including hydropower

Hydropower is currently the largest source of low-carbon power in Pakistan, accounting for 26% of the country’s electricity supply, according to IEA data.

Pakistan’s considerable water resources are tied to the Indus, one of the world’s largest rivers, which originates in Tibet and flows through the Himalayas before cutting across Pakistan and emptying into the Arabian sea near Karachi.

According to Pakistan’s Water and Power Development Authority, there is 60,000MW of hydropower potential in the country, of which 7,320MW has been developed.

China has financed several large hydropower projects in Pakistan as part of its China-Pakistan economic corridor, one faction of China’s wider Belt and Road Initiative.

This includes the operational Karot project (720MW) and two plants that are still under construction, Suki Kinari (870MW) and Kohala (1,124MW).

Karot Hydropower Plant in Pakistan's eastern Punjab province. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

In January 2023, France announced it will loan Pakistan $130m to build the Keyal Khuwar hydropower project (128MW), according to Pakistan’s News International.

In April, Saudi Arabia pledged to loan Pakistan $240m for another major hydropower project, the Mohmand Multipurpose Dam Project (800MW), according to Utilities Middle East.

The construction of major dams has previously sparked protests in Pakistan.

In 2020, hundreds of people in Pakistan-administered Kashmir protested over the Chinese-funded Neelum-Jhelum Hydroelectric Project, which diverted one of the two rivers flowing through the city, according to Voice of America.

The diversion of the river had many impacts on the city, including causing a rise in local temperatures and disruption to rainfall patterns, according to the residents. A local doctor noted that cases of hepatitis, malaria and typhoid increased after the river’s diversion.

In 2022, the plant developed a technical fault – and was “abandoned” entirely by its Chinese operators, according to India’s Economic Times.

Hydropower production in Pakistan faces threats from conflicts with neighbours that share its water resources and climate change. (See: Impacts and adaptation.)

There is currently a small number of wind and solar farms in Pakistan. They accounted for 3% of electricity generation in 2020, according to IEA data.

In its latest international climate pledge released in 2021, Pakistan says that 60% of its electricity will be generated from renewables including hydropower by 2030. This can be compared with the 29% these sources contributed in 2020.

Pakistan breaks down its renewable expansion plans further in its latest 10-year plan for power production released in 2023. It says that, by 2031, 39% of its power will come from hydro, 10% from wind and 10% from solar. (The document notes that one of the “major determinants” of its plan for expanding renewable power is the vulnerability caused by Pakistan’s current heavy reliance on imported fossil fuels.)

Pakistan’s previous 10-year plan released the year before targeted a higher 65% of power from renewables and hydropower by 2030.

Explaining the decision to pursue a large expansion in hydropower alongside other renewables, Pakistan’s international climate pledge says:

“Hydropower development in Pakistan is critical for the energy transition as it can even out the volatility of high shares of solar and wind.”

It comes after the country released an Alternative and Renewable Energy policy in 2019, which said that Pakistan “intends” to have 20% of its total electricity generation capacity from wind and solar by 2025 and 30% by 2030.

According to the World Bank, this will require Pakistan to install around 24,000MW of solar and wind by 2030, up from 1,500MW today. This represents 150-200MW a month from now until 2030, it notes.

Technicians check the solar power panels in Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo.

The World Bank’s analysis also says that this would represent a “least-cost” electricity expansion scenario, resulting in fuel savings equal to $5bn over 20 years. (And this calculation was made before the global fuel price hike fuelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.)

It adds that using just 0.07% of Pakistan’s land for solar could generate enough power to meet its current electricity demand.

(The World Bank says its analysis informed Pakistan’s targets.)

As well as saving on fuel costs, a fast expansion of renewables could help Pakistan address its mounting circular debt in the power sector (see: Politics), an expert told Pakistan’s Tribune.

In August 2022, the government announced plans to add 9,000MW of solar to the grid as part of a “solar energy initiatives” scheme, in a bid to reduce its reliance on costly fossil fuel imports, the Tribune reported. As part of the scheme, the government plans to offer tax exemptions and waive import duties, the newspaper added.

In December 2022, prime minister Shehbaz Sharif urged Turkey to invest in new solar in Pakistan, saying that the country “cannot afford the import of such costly oil and petroleum products”, according to a separate report in the Tribune.

More widely, Pakistan estimated in its 2021 international climate pledge that the transition from fossil fuels to renewable including hydropower will require $101bn in foreign investment by 2030. (See: Climate finance.)

This includes $50bn for meeting its pledge of generating 60% of its electricity from renewables including hydro by 2030.

Deforestation, wood burning and agriculture

A quarter of people in Pakistan lack access to electricity. Instead, many rely on the burning of wood, “biogas” – a gas produced from animal and plant waste – and other types of waste in order to generate energy in the home.

This is particularly true for food preparation, a task mostly undertaken by women. Only half of Pakistan’s population have access to “clean cooking” and the rest rely on polluting and inefficient cookstoves.

A woman cooks on a fire inside her house in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Credit: Steve Davey Photography / Alamy Stock Photo.

According to the South Asian news agency ANI, 68% of people in Pakistan rely on firewood. This is one of the major drivers of deforestation in the country, alongside urbanisation and food and commodity production. (Illegal logging by the Taliban has also contributed.)

When Pakistan was first established, a third of its land – more than 260,000 square km – was covered by forest. But, by 2010, forest cover fell to just 5% (around 40,000 square km), according to ANI.

Forest loss has slowed since 2010, but has not stopped completely. In 2021, Pakistan lost 0.63 square km of tree cover, causing the equivalent of 23,500 tonnes of CO2e to be released into the atmosphere, according to the Global Forest Watch.

Deforestation has impacted Pakistan’s unique biodiversity.

The country is home to: 195 mammal species, six of which are “endemic” (only found in Pakistan); 668 birds, 25 of which are endemic; 177 reptiles, 13 of which are endemic; 22 amphibians, nine of which are endemic; 198 freshwater fishes, 29 of which are endemic, 5,000 invertebrates; and 5,700 flowering plants, of which 400 are endemic.

Volunteers rescue a dolphin stuck in a canal off the Indus river, near Karachi, Pakistan. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

But, according to the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity, nature in Pakistan faces an “impending national disaster” because of human activities and degradation of habitats.

It notes that the mangrove forests of the Indus Delta, the largest of their kind in the world, declined by half from the 1970s to the mid-1990s.

Deforestation has also exacerbated the impacts of climate change, including flood risk. This is because the presence of dense forest can act as a natural flood barrier and prevent river bank erosion.

Agriculture accounts for 19% of Pakistan’s GDP and 60% of its exports, according to the Economic Survey of Pakistan 2020-21. It also provides a livelihood to 68% of Pakistan’s rural population and employs 45% of the national labour force.

Some 230,000 square km out of Pakistan’s total area of 800,000 square km are used for crop production.

The country has the world’s largest continuous irrigation system covering almost 80% of its cultivated area, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The agricultural sector is also the largest consumer of freshwater, accounting for 95% of total withdrawals, according to Pakistan’s 2021 international climate pledge.

Pakistani farmers busy loading watermelons. Credit: Pacific Press Media Production Corp. / Alamy Stock Photo.

Pakistan is among the world’s top 10 producers of wheat, cotton, sugarcane, mangoes, dates and kinnow oranges – and ranked 10th for rice production, according to the FAO.

In addition, Pakistan’s livestock sector contributes 11% to the country’s GDP and employs around 35m people, the FAO says.

Both crop and livestock production in the country face steep risks from climate change. (See: Impacts and adaptation.) In its international climate pledge, Pakistan says one of the economic sectors most at risk from climate change is the “agriculture-food-water nexus”.

Agriculture, forestry and land use accounts for around 18% of Pakistan’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

In its international climate pledge, Pakistan says it will tackle agricultural emissions through a “complete ban” on the open burning of rice stubble, solid waste and other hazardous materials.

Many farmers in Pakistan burn the remnants of rice crops between October and January to clear the land for sowing wheat. Burning rice stubble is considered the cheapest and quickest way, but drives CO2 emissions and deadly air pollution. An FAO study found 20% of Pakistan’s thick air pollution comes from crop burning.

The climate pledge does not mention new efforts to stop deforestation or reduce emissions from livestock rearing.

‘Nature-based solutions’

The idea of “nature-based solutions” to climate change is a big hit with politicians in Pakistan, with several promising to restore the country’s degraded ecosystems in order to tackle emissions and biodiversity loss.

Current prime minister Shehbaz Sharif said that nature-based solutions were at the heart of Pakistan’s climate strategy at the COP27 summit in 2022.

And former prime minister Imran Khan made international headlines in 2018 with his “Ten Billion Trees Tsunami”, a national initiative to plant enough trees to cover 26.6% of Pakistan’s land area by 2030.

According to Pakistan’s 2021 international climate pledge, the plan was for 3.3bn plants to be planted or “regenerated” across Pakistan by 2023. Then, “phase two” would see 750-800m new plants a year for six years up to 2030.

Deutsche Welle reported in 2021 that researchers and officials had raised concerns with the project. For example, the scheme had seen saplings planted in desert areas, requiring costly irrigation in order to survive, one researcher noted. A senior government official speaking on the condition of anonymity told DW that many planted saplings had died in intense heat.

The government had planted 1.5bn trees by March 2022, but the whole programme was then thrown into question when Khan was ousted from parliament in April that year, Climate Home News reported.

In September, Pakistan’s the Nation reported an official audit of the programme uncovered alleged evidence of overspending and fraud.

Following this, the Tribune reported in October that Sharif’s government had renamed the project “Green Pakistan” and slashed its annual budget from $49m to $33m.

A volunteer plants red mangrove trees near the Arabian Sea, south of Karachi, Pakistan. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

Pakistan’s 2021 climate pledge references several other large-scale nature-based projects.

This includes the Protected Areas Initiative, which aims to get 15% of Pakistan’s land under protection by 2023. To achieve the aim, the government planned to create 15 new national parks covering 7,300 square kilometres, according to Pakistan’s climate pledge. It is not clear whether this will be achieved.

It also includes an Ecosystem Restoration Initiative, which aims to restore 30% of Pakistan’s degraded forests, 5% of degraded cropland, 6% of degraded grassland and 10% of degraded wetland by 2030.

In September 2022, climate minister Sherry Rehman announced the Living Indus Project, describing it as Pakistan’s “biggest climate initiative” that has the aim of protecting and restoring the Indus river, while boosting flood resilience in its vicinity. The project was officially launched at COP27.

Reporting on the initiative, the Third Pole noted that several expert groups in Pakistan welcomed the plans. However, some raised concerns the initiative does not discuss the major impact of large hydropower projects on the Indus basin. (See: Renewables including hydropower.)

(It is worth noting that the term “nature-based solutions” is viewed with deep scepticism by some groups. Some argue that the term can too easily be misused as a cover for greenwashing, while others say it minimises the intrinsic value of nature and/or the role that Indigenous people play in safeguarding Earth’s last remaining intact ecosystems.)

Climate finance

Pakistan updated its climate pledge in 2021, to set a “cumulative conditional target” of limiting emissions to 50% of what it expects its business-as-usual levels to be in 2030. It says that 15% of this will be met by its own resources and 35% is subject to receiving climate finance.

“Climate finance” refers to money – both from public and private sources – that is used to help reduce emissions and increase resilience against the negative impacts of climate change.

Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries – who are most responsible for climate change since it first started – have pledged to provide climate finance to developing nations.

In its 2021 international climate pledge, Pakistan says that meeting its emissions targets will require $101bn in climate finance by 2030 and an additional $65bn by 2040. This includes:

- $20bn for replacing under-construction coal projects with hydropower

- $50bn for achieving its target of producing 60% of its electricity from renewables including hydropower by 2030

- $20bn to upgrade the electricity transmission network by 2040

- $18bn for buying out and closing “relatively new coal projects”

- $13bn for replacing coal projects with solar

Pakistan’s pledge adds that it will require $7-14bn per year to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

It also says that “Pakistan has enjoyed very limited access to international climate finance” so far, noting it has received money for one project from the Adaptation Fund, three projects from the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and 19 projects from the Global Environment Fund.

Carbon Brief analysis shows that Pakistan received $2.2bn in climate finance in 2020, making it the world’s eighth largest recipient that year. The UK, Germany and Japan were the countries to give the most funds to Pakistan.

Pakistan’s climate pledge also specifically calls for funds for loss and damage from climate change. (Loss and damage is a term used for the suffering already caused by climate change, see Carbon Brief’s full explainer for more information.)

It says that Pakistan needs help dealing with glacial lake outburst floods, seawater intrusions, droughts, heatwaves, tropical storms, landslides and river flooding. (See: Impacts and adaptation.)

The pledge estimates that damages to infrastructure alone will account for around 70% of the $7-14bn in adaptation funding required per year.

Impacts and adaptation

Facing a wide range of climate disasters and with a large vulnerable population, Pakistan is often described as one of the countries most affected by climate change globally.

According to one 2021 climate risk index, Pakistan was the eighth most-affected country from 2000-19.

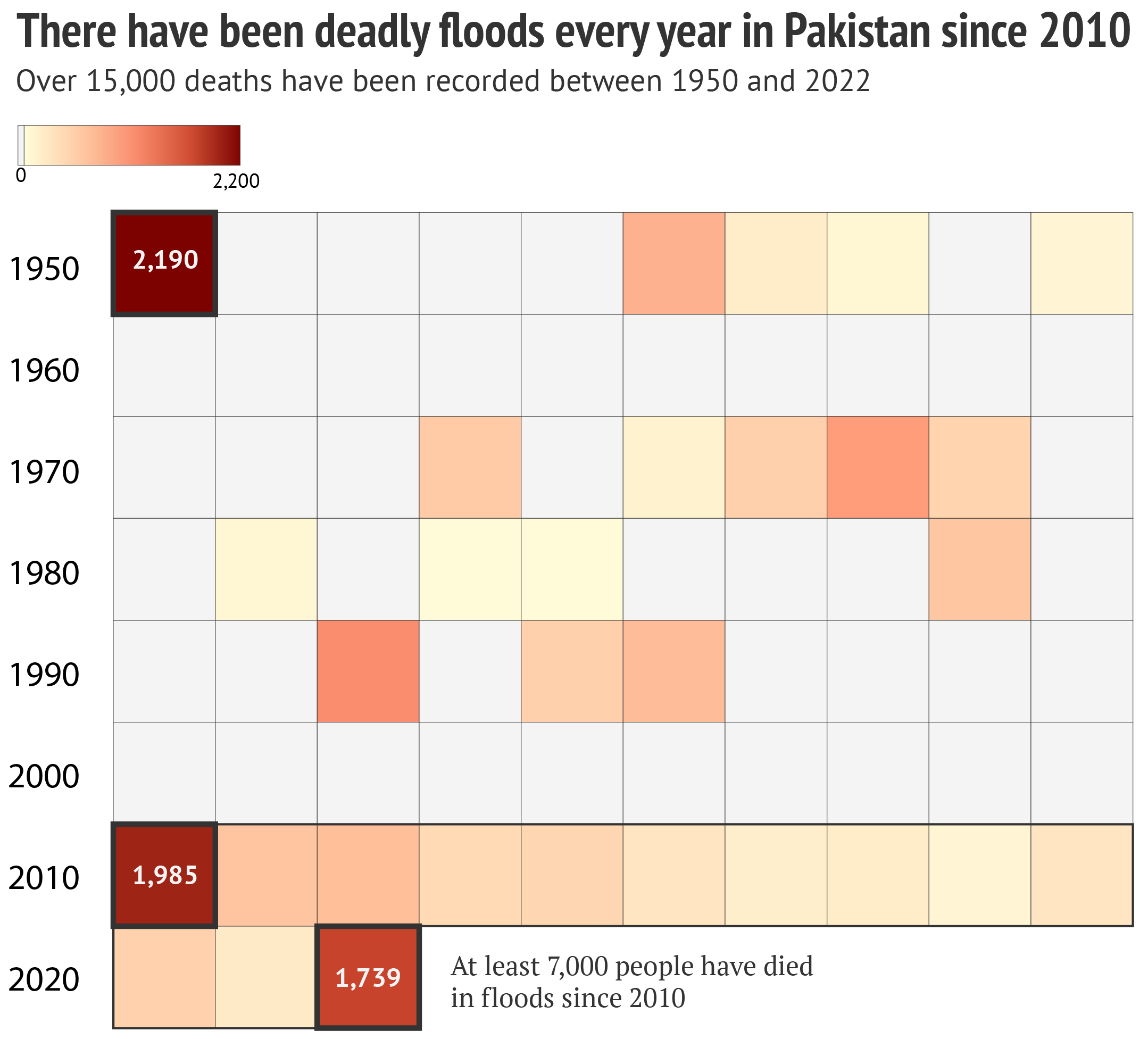

One of the greatest climate impacts facing Pakistan is flooding linked to extreme rainfall and the overflow of rivers, which tend to be close to human settlements and agricultural land.

The country has faced deadly floods every year for the past 13 years, with 2010 and 2022 among the worst for number of people killed and area of land affected.

(The year 1950 was also particularly deadly for flooding in Pakistan, despite less land being affected than in 2010 and 2022. At this time, far fewer flood defences were in place than today, meaning a smaller flood could have a larger human impact.)

Source: Federal Flood Commission.

From June to August 2022, Pakistan received nearly 190% more rain than its 30-year average. This drove catastrophic flooding affecting 33 million people and killing more than 1,700.

A study published in the wake of the floods found that these record rains were made 75% more intense by human-caused climate change. (As temperature rises, the air can hold more moisture, which can lead to heavier rainfall.)

Other factors that made the floods so deadly were the proximity of human settlements to flood plains, an outdated river management system and ongoing political and economic instability, the study said.

In February 2023, the Guardian reported that thousands of families remain homeless and without livelihoods months after the floods.

The 2023 floods also caused an estimated $30bn in financial losses.

In January 2023, Pakistan and the UN held a joint summit in Geneva to raise funds to help rebuild the country in the wake of the floods. At the event, over $8bn was pledged by other governments, multilateral banks and private donors, Climate Home News reported.

Climate Home News also reported that the World Bank was accused of “sleeping through” the floods by failing to spend pledged finance on new flood defences for Karachi ahead of the disaster.

Top: Homes are surrounded by floodwaters in Sohbat Pur city, a district of Pakistan's southwestern Baluchistan province, on 30 August 2022. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

Bottom: A woman takes refuge after leaving her flood-hit homes in Jaffarabad, a district of Baluchistan province, Pakistan, on 21 September 2022. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

Additionally, Climate Home News reported that cuts to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Pakistan branch left them unable to respond adequately to the 2023 disaster. The publication reported:

“In 2016, OCHA had around 35 staff in Pakistan and a budget of more than $5m. By 2021, its budget was $1.1m and in 2022 it employed seven people.”

Pakistan’s Tribune in February 2023 reported that several large international companies, including Alphabet and Meta, had pledged funds in response to the flooding despite allegedly spending a decade avoiding paying taxes on their operations within the country.

High-intensity rainfall in Pakistan is expected to “significantly increase further” if global temperatures reach 2C above pre-industrial levels.

As well as experiencing river and flash flooding, the country’s many mountains and glaciers make it prone to deadly glacial lake outburst floods.

Pakistan contains more glacier ice than anywhere else in the world outside of the polar regions.

The Chiatibo glacier in the Hindu Kush mountain range in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhunkwa Province in Pakistan. Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

Glaciers – which are essentially frozen rivers – are fast disappearing because of climate change. Research found that two-thirds of glacier ice in the High Mountain Asia region, which covers part of Pakistan along with neighbouring countries, could vanish by the end of the century under a scenario of very high emissions.

As glaciers melt away, they can leave behind large pools of meltwater in the grooves of where the ice once was. These are known as glacial lakes. If the water rises too high or surrounding land or ice gives way, the lake can burst, unleashing a tsunami-like wave that can be deadly for people living nearby.

A study published in February 2023 found that Pakistan has one of the highest populations exposed to glacial lake outburst floods in the world. In the High Mountain Asia region, every person lives within roughly six miles of a glacial lake, according to the study.

In 2022 alone, there were at least 16 glacial lake outburst incidents in Pakistan’s northern Gilgit-Baltistan region, CNN reported. Communities living in the region have been forced to migrate seasonally or permanently because of the outbursts, according to Pakistan’s Centre for Strategic and Contemporary Research.

As well as causing floods, the melting of Pakistan’s vast glaciers is threatening the water supply of hundreds of millions of people. The disappearance of Pakistan’s glaciers also threatens the culture and unique way of life of Indigenous people living in the country’s mountainous regions.

Pakistan is also highly at risk from heatwaves – and has experienced some of the highest temperatures recorded anywhere on Earth.

The highest temperature recorded in Pakistan is 53.7C. This occurred during a 2017 summer heatwave where above-50C heat was recorded for four consecutive days in the city of Turbat, Balochistan. Such temperatures are above the limits of what humans can tolerate, without seeking shelter.

In 2022, Pakistan experienced an unusually early heatwave, recording temperatures of 49C in April. This heat, which killed 90 people across Pakistan and India, was made 30 times more likely by human-caused climate change, according to a rapid analysis.

A young man pours water over himself during a heatwave in Hyderabad, Pakistan, on 4 April 2022. Credit: Zuma Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

Just 13% of people in Pakistan’s cities have access to air conditioning, according to Asia News Network. The figure is just 2% in rural areas.

Global temperature rise of 2C will cause heatwaves similar to what occurred in Pakistan in 2022 to become a further 2-20 times more likely.

Pakistan is also significantly affected by drought. While record rains have occurred in some parts of the country, “some dry areas have become drier as they have experienced less than normal precipitation”, Pakistan says in its 2021 international climate pledge.

In 2019, Pakistan’s largest provinces of Balochistan and Sindh were gripped by a major drought affecting more than 500,000 people. Reporting on the disaster at the time, the International Federation of Red Cross said “animals are dying and people are struggling to feed themselves”.

The country is also at risk from tropical storms. In 1970, Pakistan experienced the deadliest storm in history when Cyclone Bhola killed 500,000 people. More recently, Pakistan experienced heavy rainfall from Tropical Cyclone Gulab in 2021.

Pakistan has the third-highest levels of air pollution in the world after China and India. Each year, 128,000 people die prematurely due to toxic smog, mainly driven by fossil fuel use for power, industry and transport.

In 2021, Pakistan announced it was developing its first National Adaptation Plan in order to prepare for the impacts of climate change. It is due to be published this year.

Notes

Graphic by Tom Prater and Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief.

Data for energy consumption comes from the International Energy Agency. Unlike earlier country profile infographics, exajoules (EJ) have been used instead of millions of tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) as the unit of energy consumption.

Data for greenhouse gas emissions by sector and gas in the infographic is a combination of datasets.

The sectoral values for CO2 are from the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) database. “Other sectors” includes agriculture, industrial processes, waste and the production, transformation and refining of fuels.

Values for methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are taken from a dataset published in Scientific Data by Dr Matthew Jones of the University of East Anglia, and collaborators. This dataset, in turn, obtains these values from the PRIMAP database. The figures for these gases cover all sectors, including land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF). Values for F-gases are taken directly from the PRIMAP database.

The LULUCF label in the chart only covers CO2. These figures come from the Jones et al. dataset, which obtains them from the Global Carbon Project. Note that there is significant uncertainty around LULUCF emissions data, and other databases may have very different figures.

Per-capita emissions in 2023 are based on total emissions in the Jones et al. dataset, and therefore do not include the minor contribution of F-gases. Population data is from the World Bank.

The ranking of Pakistan as the 18th largest emitter in 2023 is also based on the Jones et al. dataset. It includes LULUCF emissions, and covers all greenhouse gases apart from F-gases.

The emissions figures in this article were updated in June 2025 to reflect changes in Carbon Brief’s methodology.