This article is part of a week-long special series on loss and damage.

Small-island nations have been sounding the alarm about climate change for more than three decades, fearing a future in which their communities and homes are engulfed by rising seas.

From the moment diplomats and leaders first gathered at the UN in the early 1990s to discuss the issue, these states began asking for help to deal with climate-related “loss and damage”.

Many vulnerable countries view UN climate negotiations as a way to secure much-needed funds from those they view as historically responsible for climate change. However, many developed countries have resisted being held financially accountable.

Over the years, negotiations have yielded numerous “work programmes” and “dialogues” on loss and damage, but have so far failed to generate the one thing small-island nations have wanted since the beginning – money.

In this interactive timeline, Carbon Brief has delved into the archives, talked to seasoned negotiators and interviewed activists about the struggle to elevate this issue, from a niche piece of UN jargon, into one of the defining issues in international climate politics.

This article is part of a week-long special series on loss and damage.

In October 1987, following unprecedented floods in his nation’s capital Malé, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, then president of the Maldives, addresses world leaders at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Vancouver, Canada, on the topic of rising temperatures and sea-level rise.

Several months before NASA scientist Dr James Hansen’s famous testimony to US Congress, Gayoom describes the threat posed to his country, most of which lies less than a metre above sea level. The speech is called "death of a nation".

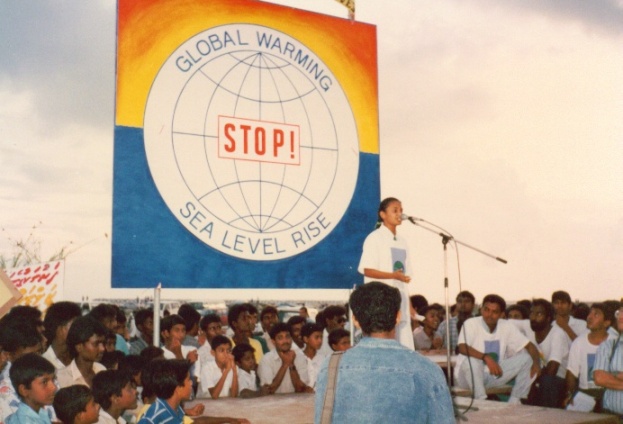

Delegates and ministers from 14 island states gather in November in Malé, the capital of the Maldives, for the Small States Conference on Sea Level Rise.

The first event of its kind, the conference also sees one of the first ever calls for global climate action – dubbed the Malé Declaration.

Among the document’s various prescient comments, it contains a call from small-island leaders for “all states of the world family of nations to…consider ways and means of protecting the small states of the world which are most vulnerable to sea level rise”.

Recognising the shared challenges facing them, small-island states meet for the first time as a group in 1990, at the Second World Climate Conference in Geneva. This marks the formation of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), which today has 39 members and is a key negotiating alliance in UN climate talks.

Ever since its inception, AOSIS has been the driving force behind loss-and-damage discussions.

A key figure in these early events is Robert Van Lierop, a US lawyer whose parents had emigrated from Suriname and the Virgin Islands. Following time spent working in civil-rights law and making films about anticolonial struggles in Mozambique, Van Lierop was approached to serve as Vanuatu's UN ambassador, having provided the Pacific island nation with assistance when they petitioned the UN for independence.

Van Lierop is appointed as the first AOSIS chair. When the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee is set up to establish the world’s first climate treaty, he is also chosen to chair a working group – the first time that an island nation has been given a leadership position within a UN forum.

In these early days, with little concrete evidence for the impacts of climate change on extreme weather and sea-level rise, Van Lierop advocates for the precautionary principle within the process, stating:

“We do not have the luxury of waiting for conclusive proof…The proof, we fear, will kill us.”

The first-ever reference to “loss and damage” in climate negotiations emerges as the world gears up for the first international climate agreement.

Acting for Vanuatu on behalf of AOSIS, Van Lierop proposes an “insurance mechanism” for inclusion in the forthcoming UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

It includes a very specific request for “industrialised” nations to pay for the “loss and damage” that would harm vulnerable small island nations as a result of rising sea levels.

This is decidedly out of step with other nations, who largely assume the goal of climate diplomacy will be restricted to cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

But Espen Ronneberg, from the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, who has been involved in climate change negotiations for Pacific island nations since 1992, tells Carbon Brief why, for them, adapting and preparing for climate change was already a priority at this stage:

“From the island countries, we were seeing impacts galore, so we were quite worried…There was also the realisation, particularly for the most vulnerable of the island countries, that there would be impacts that we probably couldn't adapt to.”

While their proposal is called an “insurance mechanism”, it is more of a global fund – nations would pay into it on the basis of their historical responsibility for climate change and their capacity, which would be assessed based on GDP.

This approach is modelled on existing conventions that were designed to provide compensation for damage resulting from nuclear incidents and oil spills.

Despite this precedent, it is not well received by developed nations.

A paper co-authored by Van Lierop and other small-island experts several years later says their idea was “not surprisingly, viewed as anathema by the developed countries. It will probably remain so for the foreseeable future.”

In the end, the AOSIS proposal does not make it into the convention.

US diplomats, fearing that climate change would open up as another avenue by which developing countries could demand money, stick firmly to a position summarised by then-lead US climate negotiator Robert Reinstein as: “No on targets, no on money”.

Prof Daniel Bodansky, a legal expert and former climate change coordinator at the US Department of State, tells Carbon Brief that money was an issue from day one:

“The negotiations of Article 4.3 and 4.4 of the Framework Convention, which were the finance provisions, were among the most contentious. Exactly what developed countries would commit to in terms of finance was very much fought over.“

Nevertheless, the influence of the AOSIS idea can be seen in the text.

Specifically, there is a reference to “threats of serious or irreversible damage” arising from climate change, tying into the idea that loss and damage is about impacts that cannot be dealt with. Most explicitly, Article 4.8 mentions “insurance” to help meet the needs of developing countries, echoing the original AOSIS proposal.

There is also discussion of the need for countries to adapt to the impacts of climate change. While later on, the topic of loss and damage would be separated from adaptation, for many years the two went hand-in-hand.

In the following years, small island states in particular continue to focus on loss and damage-related issues, but it would be some time until they come to the fore. “It just all kind of went underground for a while,” Linda Siegele, a lawyer who represents small-island states in climate negotiations, tells Carbon Brief.

After lengthy disputes, the Kyoto Protocol is established at COP3 and commits developed countries to cutting their emissions, on the basis that they are better equipped to do so and also historically responsible for climate change.

The protocol is mainly focused on mitigation, although it also launches the Adaptation Fund to finance adaptation projects in developing countries. There is also a mention of “insurance” as a potential mechanism for minimising the “adverse effects of climate change”.

Insurance next emerges as an issue at COP7 in the Moroccan city of Marrakech, which also marks the first COP to result in significant outcomes on climate adaptation.

Siegele says that, once again, small islands states were behind this push amid slow progress on getting the Kyoto Protocol off the ground:

“They were saying, well, if Kyoto doesn't ever come into force…we've got to start dealing with the residual impacts that will happen because we're not mitigating.“

The resulting Marrakech Accords contain a decision to consider “insurance-related actions” to meet developing countries' needs.

Informally dubbed an “adaptation COP”, COP10 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, results in more notable outcomes to help developing countries in particular to prepare for climate impacts, as the scientific evidence for such impacts had begun to mount.

The resulting Buenos Aires programme of work on adaptation and response measures is broadly welcomed, but it is bittersweet. Language in Article 4.8 of the UNFCCC means that the issue of adaptation has become wrapped up with so-called “response measures” – meaning compensation for oil-producing countries as demand falls for their products.

Under pressure from Saudi Arabia and other oil producers, including the US, this means that any action taken to help vulnerable countries deal with climate impacts have to be matched with help for countries whose fossil-fuel industries are threatened by climate action.

“The two cannot be equated by anyone with logic, but that was, unfortunately, the compromise that we ended up having to make,” says Ronneberg. Experts say this intractable issue slowed down progress on adaptation and, by association, loss-and-damage for years.

COP11 in Montreal, Canada, sets the ball rolling for future action on adaptation and loss and damage with a “dialogue on long-term cooperative action” – which paves the way for the Bali action plan two years later. One component of this is “addressing action on adaptation”.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh, on behalf of the least developed countries (LDCs), calls for compensation for damages caused by climate change, in a foreshadowing of later conversations around loss and damage.

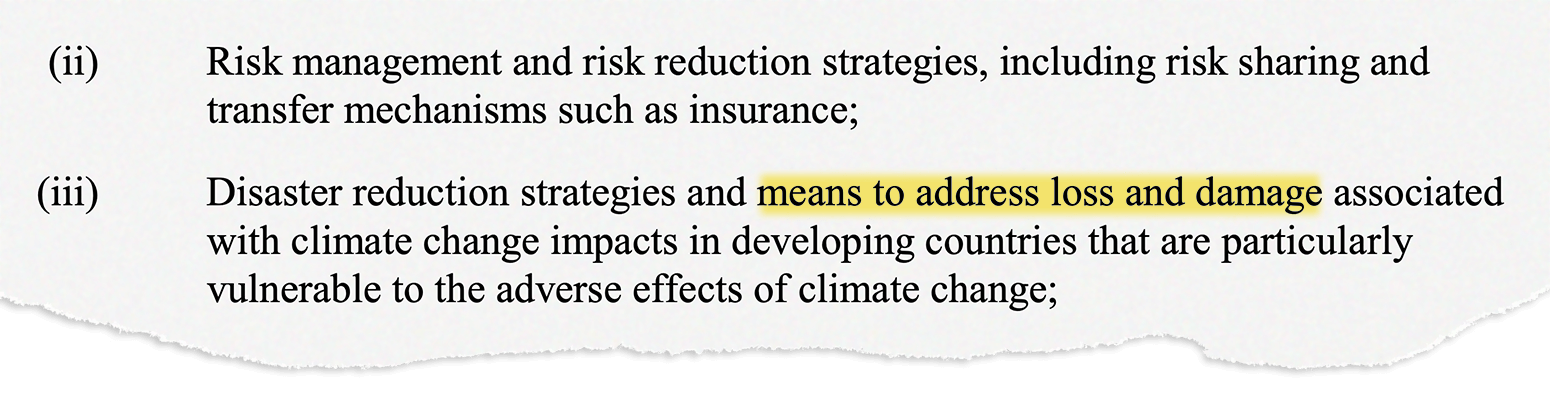

COP13 on the Indonesian island of Bali marks the first time in the history of UN talks that “loss and damage” makes it into a negotiated text.

The conference as a whole focuses on discussing a successor agreement to the Kyoto Protocol. Among the priorities listed in the resulting Bali Action Plan is a decision to provide “enhanced action on adaptation”, establishing adaptation as a separate “pillar” of negotiations, independent from mitigation.

This includes not only strategies to help countries reduce climate risk, such as insurance, but, more explicitly, “means to address loss and damage”.

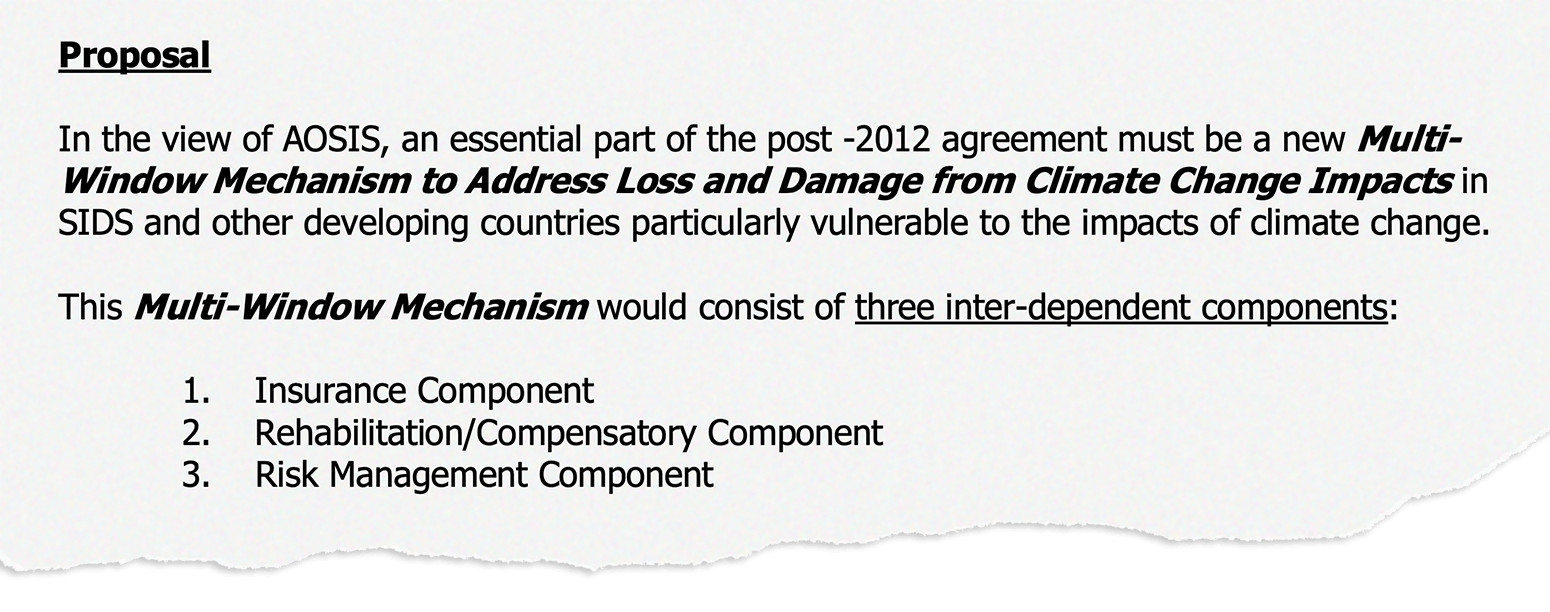

With adaptation now being discussed at a high level in the UN process, COP14 in Poznań, Poland, sees AOSIS make another significant loss-and-damage intervention.

The group proposes a new mechanism to provide insurance schemes, risk management and compensation to vulnerable countries, to address the “progressive negative impacts of climate change”, such as sea-level rise.

Once again, the small-island nations say it should be paid for by developed countries based on their historical emissions. “I think when that came on the table is the point in time when developed countries started to be concerned,” says Siegele.

In particular, industrialised countries begin trying to focus discussions on insurance and risk management, and away from compensation. Bodansky explains why:

“If the climate regime is backward looking, trying to assign blame for what's happened, which would then provide a basis for liability and compensation, countries aren't going to participate.“

The year also sees civil society groups begin to join the call for loss and damage. In a paper titled “Beyond adaptation”, WWF cites the most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which concludes:

“There is high confidence that neither adaptation nor mitigation alone can avoid all climate change impacts“.

In submissions suggesting text for the outcome of COP15 in Copenhagen, Denmark, the African Group joins AOSIS in calling for an “international mechanism to address the unavoidable loss and damage”.

India, Brazil, Bangladesh, Costa Rica and Panama also submit text concerning loss and damage, showing that this is no longer merely a small-island issue.

However, despite hopes of a new plan to succeed Kyoto, Copenhagen ultimately ends in disarray amid clashes between some of the major emitters and developing nations. References to a loss-and-damage mechanism are removed from the resulting text.

Yeb Saño, former lead negotiator for the Philippines, tells Carbon Brief that despite the collapse of COP15 talks, this was a critical moment in the history of loss and damage:

“I would say loss and damage only attained a level of importance after Copenhagen…that was a time when mitigation could have saved everything, and then it did not work. Kyoto collapsed, and then adaptation was the emphasis, and then we started to realise there are countries that cannot adapt – there are communities that will incur loss and damage.“

In the months that follow COP15 in Copenhagen, the divide along developed and developing country lines over loss and damage grows.

At negotiations in Bonn, AOSIS gathers support for its proposals from nations as varied as Ghana and China. However, the US, the EU and other developed countries push back, in particular opposing any notion of compensation.

Despite these differences, a compromise is reached at COP16 in Cancún, Mexico.

Parties agree on a two-year work programme on loss and damage. The text includes discussions of risk reduction, rehabilitation and insurance, but not compensation.

More broadly, COP16 sees a significant increase in adaptation action, with agreement on a Cancún Adaptation Framework. This includes elements that would later find their way into loss-and-damage decisions, including mentions of “early warning systems” and insurance.

Despite the developed-versus-developing split that has emerged on the issue, the Group of 77 and China (G77), which represents the interests of developing country parties in the UN climate process, cannot agree on what they want from the work programme at COP17 in Durban, South Africa.

Nevertheless, sub-groups within the G77, notably AOSIS and the African Group, support each other in calls for a “mechanism” within the UN process to address loss and damage. Ultimately, the final text that emerges includes a reference to such a mechanism.

COP18 in Doha, Qatar, takes place against the backdrop of drought across much of east Africa and a major typhoon striking the Philippines. Meanwhile, major emitters including the US, Japan, Russia and Canada have all made it clear they will not commit to further emissions cuts under the Kyoto Protocol.

It is in this setting that discussions of loss and damage take on an added urgency.

In the run-up to the meeting, Dr Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD), gathered representatives from the least developed countries (LDCs) in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and invited experts to talk through specific topics, including loss and damage. He tells Carbon Brief:

“That really was an eye-opener for the LDC negotiators to say, well, this affects us. It’s not just a small-island thing…Ever since then, the LDC group has been very active on loss and damage.“

This allows the whole of the G77 to unite and back the creation of a loss-and-damage mechanism. “Rich countries were caught unaware” by the strength of feeling around it, Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network, tells Carbon Brief.

The year has also seen the launch of the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) group. This new subset of developing countries has a strong focus on emphasising the historical responsibility of developed countries for climate change and, as such, makes loss and damage a priority.

Meanwhile, 47 NGOs have sent an open letter calling on parties to introduce a loss-and-damage mechanism for “compensation and rehabilitation”.

"Doha was the main turning point because I had not seen the momentum from civil society and governments [before],” Sandeep Chamling Rai, a senior advisor in global climate adaptation policy at WWF tells Carbon Brief, recalling the first-ever ministerial roundtable discussion on loss and damage taking place late at night.

Another breakthrough comes at COP18, with the resulting Doha decision marking the first time that loss and damage is formally established as part of the architecture of the Convention, highlighting the “fundamental role of the Convention in addressing loss and damage”.

It also includes a decision “to establish, at its nineteenth session [COP19], institutional arrangements, such as an international mechanism…to address loss and damage”.

The Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage (WIM) is established at COP19 in Poland, fulfilling the previous year’s pledge.

This mechanism includes functions to boost loss-and-damage understanding, strengthen collaborations and enhance “action and support”. However, the decision only “requests” that developed countries provide financial assistance.

As Saño notes, the decision on the WIM was a “big surprise” to many people, as it was still such a contentious issue for developed country parties, including the US, the EU and Australia. However, he tells Carbon Brief:

“If the G77 is united, it can happen, because that's first and foremost the most difficult battleground if we are to get anything done.“

The event once again takes place as a major storm, Typhoon Haiyan, strikes the Philippines, and Saño – who is leading the nation’s delegation at the time – is commended following an emotional speech in which he describes loss and damage as a “reality today across the world”.

Negotiations around the WIM are lengthy and fractious. Developing country parties are clear that they consider “loss and damage” to refer to impacts “beyond adaptation”, while the US and Australia want it placed under the Cancun Adaptation Framework.

At one point, G77 representatives walk out of the negotiations and, the next day, they are followed by hundreds of civil society members.

In the end, a compromise is reached, following a one-hour huddle involving dozens of parties and centred around negotiators Sai Navoti of Fiji – representing the G77 – and Todd Stern of the US. Loss and damage remains under adaptation, but new language is inserted to emphasise that it could involve impacts that cannot be “reduced by adaptation”.

Developing country negotiators had been prepared for the talks to collapse altogether. Madeleine Diouf Sarr, a Senegalese negotiator and current chair of the LDC group, tells Carbon Brief they were “running out of patience” at this point:

“Tension was rising, and then we got the WIM. It was more watered down than what we had been asking for, but it established the framework for a mechanism to address loss and damage and paved the way for loss and damage to become the third pillar of the Paris Agreement.“

When COP21 comes around – and with it the landmark Paris Agreement – loss and damage appears in the text as the “third pillar” of climate action, alongside cutting emissions and adapting to climate change.

Article 8 of the Paris Agreement is dedicated to loss and damage. Notably, it is distinct from references to adaptation – showing its development into an issue in its own right.

According to Rai, following the momentum in Warsaw and COP20 in Lima, this “was not a big surprise”.

Nevertheless, it is once again the result of hard-fought negotiations.

Many developing country parties still see loss and damage as being essentially a euphemism for “liability and compensation” – a means by which to extract money from the developed nations they see as responsible for climate change. But such language is a clear red line for those nations, particularly the US.

Kaveh Guilanpour, a former negotiator for both the EU and AOSIS, tells Carbon Brief unambiguously that “an explicit mention of compensation and liability would have prevented the US from entering the Paris Agreement”. He also notes that this is not a unique position, stating that “there's a very large number of countries that have exactly the same position and hide behind the US”.

Going into COP21, the negotiating text contains an option from developing countries that included liability and compensation, and another from the Umbrella Group – including the US – that deletes all mentions of the topic altogether.

Despite this, US secretary of state John Kerry explicitly says they are “not against” loss and damage, but need it in a way that “doesn’t create a legal remedy” as they will not get it past Congress.

Over the course of the two-week summit, a landing ground is reached between the US, including Kerry and president Barack Obama, and small-island leaders.

The final agreement includes supportive text on loss and damage. But it is accompanied by an infamous decision text, that confirms countries such as the US cannot be held legally responsible for loss and damage.

COP22, the second major climate summit to take place in the Moroccan city of Marrakech, is largely overshadowed by the election of US president Donald Trump, which immediately raises the possibility of the world’s biggest historical emitter leaving the Paris Agreement almost as soon as it has been established.

However, normal processes also continue, including the first review of the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM), which, having been established three years earlier at COP19, has now been brought under the Paris Agreement.

Parties agree on a five-year workplan for the WIM’s executive committee that will see it consider issues including the slow-onset impacts of climate change, non-economic losses and migration. Already, a key criticism is that the WIM is failing to make progress on providing finance for loss and damage.

Despite its location in Bonn, Germany, COP23 is a “Pacific COP” and has a Fijian presidency. With a small-island state at the helm, loss and damage is viewed as a key priority, amid growing awareness of how these issues are playing out on the ground.

Indeed, the introduction to the decision on the WIM’s executive committee report, which emerges from the event, notes “concerns raised by parties on the increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters”.

Nevertheless, vulnerable nations want to move the conversation beyond technical reports and onto securing resources.

The G77 pushes hard to get a standing agenda item on loss and damage beyond reports from the WIM. Such reports are viewed as technical, rather than political, and therefore inadequate to secure finance for loss and damage.

This effort is led by G77 coordinator Joel Suarez Orozco, whose native Cuba has been hit by the powerful Hurricane Irma earlier in the year.

However, developed countries oppose this proposal and parties ultimately settle on the Suva expert dialogue. Named after the capital of Fiji, this “dialogue” is meant to provide space “to explore a wide range of information, inputs and views on ways for facilitating the mobilisation and securing of expertise, and enhancement of support, including finance, technology and capacity-building”.

There is also progress on a relatively palatable form of loss and damage support for developed countries – namely, insurance. Fiji prime minister Frank Bainimarama backs plans for an initiative called the "InsuReslience Global Partnership", with a target of providing insurance for 400 million poor and vulnerable people.

Parties meet in Katowice, Poland, for COP24 to thrash out the “rulebook” that will be used to implement the Paris Agreement. Developing countries see some success as they manage to push for the recognition of loss and damage in the rules.

First, loss and damage is added as a component of the “global stocktake”, which tracks progress towards Paris Agreement goals.

Second, it is also included in the outcome on “transparency”, stating that parties “may provide, as appropriate”, information about loss and damage when reporting on climate metrics.

Yet there is still slow progress on finance. The Suva expert dialogue took place earlier in the year and saw virtually no participation from developed countries. But one clear conclusion was that insurance would not be sufficient to meet developing countries’ needs.

In light of the recently released IPCC report on 1.5C of warming, which made clear the threat facing small-island nations, in particular, AOSIS chair and Maldives environment minister Thoriq Ibrahim wrote ahead of the summit that loss and damage needed to be elevated in the negotiations:

“It would also be suicide not to use every lever of power we have to demand what is fair and just: the support we need to manage a crisis that has been thrust upon us.“

Calls for loss-and-damage finance persist at COP25 in Madrid, Spain, as the second review of the WIM gets underway.

The G77 is united around a handful of loss-and-damage positions, some of which make their way into the final texts. However, what negotiators refer to as their “key demand” – a call for “new and additional” finance from developed countries – is not among them, following negotiations that overrun by two days.

There are some provisions for finance in the WIM decision text, including an entry point for the executive committee to link with the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a major source of climate finance.

In addition, there is an agreement to form an “expert group” to investigate “action and support” – terms that refer to finance – under the executive committee.

Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network tells Carbon Brief that the delay in forming this group, the fifth to be established in the WIM, was a demonstration of developed countries’ resistance to anything that could facilitate loss-and-damage finance. “There was no need for all the political drama that has happened over the last few years,” he adds.

A final important outcome is the launch of the Santiago Network, named after the capital of Chile, which holds the COP presidency. This body is proposed to help provide technical support directly to developing countries. Debates over getting it up and running will continue in the following years.

After being delayed for a year due to the Covid-19 pandemic, COP26 in Glasgow, UK, sees loss and damage develop into a significant issue. Much of the excitement around the topic comes as the G77 once again unite in an ultimately unsuccessful bid to establish a finance facility for loss and damage.

For many participants, there is a sense that loss and damage is now an issue that cannot be overlooked at the negotiations. “Now the science is becoming much clearer compared to what it was in 2008 or even during Paris,” says Sandeep Chamling Rai, a senior advisor in global climate adaptation policy at WWF.

In the end, the negotiations settle on another “dialogue”, in which diplomats and experts can “discuss the arrangements” of funding for loss and damage. With the lacklustre “Suva dialogue” from 2017 still fresh in their minds, some observers say they fear a “neverending talkshop”.

“It’s another excuse for delaying the process of taking real action to address loss and damage,” Ineza Umuhoza Grace, co-director of the Loss and Damage Youth Coalition, tells Carbon Brief.

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s first minister, causes a stir when she announces the first-ever dedicated national funding for loss and damage – a relatively small contribution of £2m.

Yet with wider resentment brewing over developed countries’ failure to meet the $100bn climate finance target they had set themselves for 2020, it is clear at the event that there is little appetite from these nations to set up new funding streams for loss and damage.

There is, however, more talk of insurance schemes, and the final COP26 decision text “urges” developed countries to provide funds to operationalise the fledgeling Santiago network.

The first session of the Glasgow dialogue kicks off at the June intersessional negotiations in Bonn, Germany, in the run-up to the next COP in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

At the end of COP25, developing nations made it clear that they were not happy with the dialogue being the main loss-and-damage outcome. At the launch of the session in Bonn, AOSIS lead negotiator Conrod Hunte reiterates that they made this concession on the condition that the dialogue would culminate in a finance facility.

Meanwhile, the US argues at the talks that they still do not think loss and damage requires a new fund, pointing to existing sources of climate finance and humanitarian aid.

However, former EU and AOSIS negotiator Kaveh Guilanpour tells Carbon Brief that, from his perspective, developed country parties, including the US and EU, are now showing notable engagement on this topic and are helping to shape the loss-and-damage conversation:

"I think what we're going to start getting now is a dynamic where the higher capacity parties are actually starting to help shape what that looks like in the way that they did for mitigation."

A key battleground at the talks in Bonn is developing countries pushing to have loss-and-damage finance added as a separate agenda item at COP27.

After the session closes, UNFCCC executive secretary Patricia Espinosa (who has recently been replaced by Grenada’s Simon Stiell) announces that “matters relating to funding arrangements for addressing loss and damage” will be on the provisional agenda.

This means that three decades after such an idea was first proposed by AOSIS, loss-and-damage finance could finally be prioritised at the upcoming COP.