On a speedboat in the Arctic Ocean, a team of scientists are hurtling towards a glacier known as Blomstrandbreen, an 18-km-long river of blue and grey ice.

Blombstrandbreen sits on top of Svalbard, an island located at 79 degrees north in the Arctic Ocean.

The terminus of the glacier directly faces the sea – and, to get close, the boat must navigate car-sized chunks of ice that have recently calved off the glacier.

Moser makes the approach to the Blomstrandbreen glacier (pictured bottom right) Credit: Daisy Dunne.

As the boat slows down, the whirr of its engine is replaced by the sound of these chunks of glacier ice rapidly melting – similar to a chorus of dripping taps.

Accompanying this is a strange cracking and popping sound, resembling popcorn in a microwave.

Carbon Brief visited Svalbard in September 2024 with the support of the British Antarctic Survey. Read more:

Svalbard: How it feels to be a climate scientist in the fastest-warming place on Earth

“That sound is the air bubbles in the ice escaping as it melts,” explains Dorothea Moser, an ice core scientist at the British Antarctic Survey. “The air is probably nearly 200 years old. It’s from the Victorian times.”

The air bubbles trapped within glacial ice tell a story of Earth’s history.

The composition of gases contained within each bubble can help to inform scientists about the levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere at the time when the ice was formed.

Researchers study the unique historical records contained within glaciers by drilling and removing ice cores.

However, such information is at risk of being lost as glacial ice rapidly melts because of climate change.

Moser is part of a team of researchers that is racing to investigate the extent to which climate change is affecting records stored within glacial ice – and if there is any way to salvage this information once melting has taken its toll.

To hear more about Moser’s work at the UK’s Arctic Research Station, watch Carbon Brief’s recording of a webinar broadcast live from Ny-Ålesund in 2024.

Right to the core

Glaciers form when snow builds up over many years, with the layers on top weighing down and compressing the bottom layers into ice.

This ice contains trapped air bubbles, chemicals, dust and other particles which can be studied to gain vital information about past climates, ranging from hundreds to thousands of years ago.

This is known as "proxy data" because it provides an indirect record of the Earth’s past climates.

To study this information, scientists use drills to take large cylinders of ice from ice sheets and glaciers. These are known as ice cores.

Ice cores have been used to help researchers map out the close relationship between global temperatures and atmospheric CO2 levels over thousands of years.

However, the information contained within ice cores is being put at risk as climate change drives dramatic glacier retreat across the world.

Increasing air temperatures and more frequent heatwaves are causing the surface of glaciers to melt away more quickly.

Meanwhile, rising ocean temperatures are having a particularly large impact on marine-terminating glaciers, such as Blombstrandbreen. Warmer waters lap directly against the terminus of such glaciers, melting them from below and causing calving events – when the ice breaks away – to occur more frequently.

Research shows that the net ice loss from glaciers has more than doubled since 2000\.

If temperatures exceed 1.5C above pre-industrial levels – the most ambitious aim of the global Paris Agreement – half of the world’s glaciers are expected to disappear by the end of the century. (The world is currently on track for 2.7C of warming.)

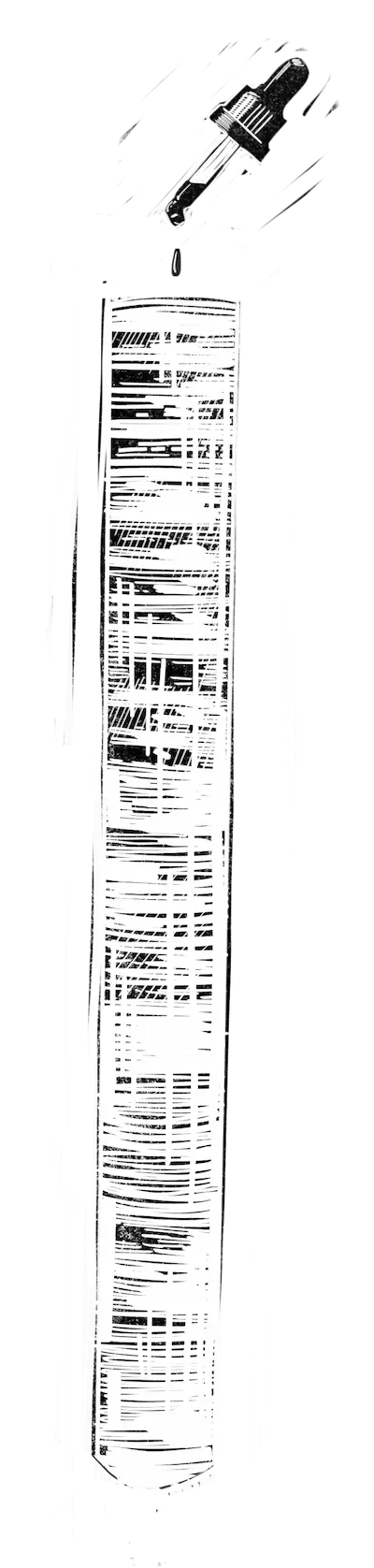

Analysing ice core samples. Credit: Dorothea Moser

Glaciers in Svalbard – of which there are thousands – are particularly vulnerable. The Arctic archipelago is the fastest warming place on Earth, heating up seven times quicker than the global average.

The dramatic decline of glaciers has prompted calls for scientists to drill for and preserve ice cores containing precious climate data while they still can.

But there is a problem. Researchers have found that the rapid melting of glaciers has led to more meltwater protruding deep into the ice, washing away compounds and potentially disrupting the climate signal they preserve.

“If you imagine an ice core like a book containing important information, what is happening is almost like someone has spilled a cup of tea all over the pages,” Moser explains.

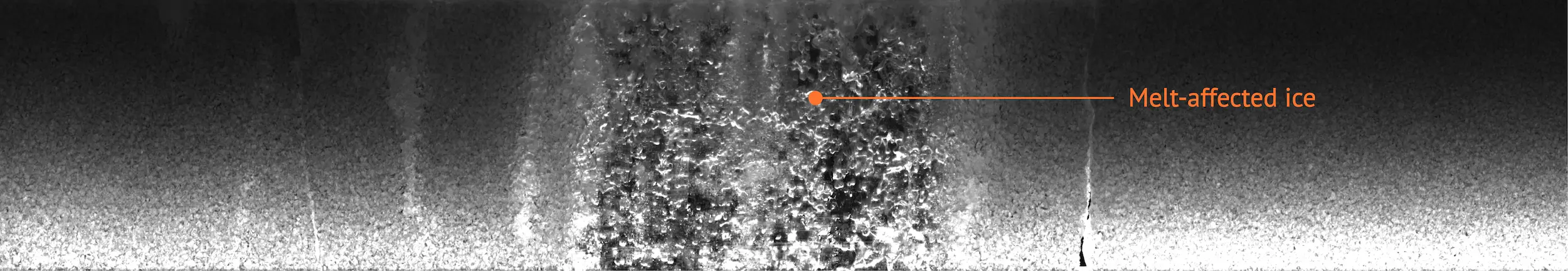

Ice cores that have been affected by meltwater intrusion often bear distinctive translucent rings. These can be seen in the video to the side, which shows Moser in her laboratory at the University of Cambridge slicing a melt-affected ice core down the middle.

The image below shows a backlit cross section of a melt-affected ice core, illustrating how meltwater can change the physical appearance of the ice.

A backlit cross section of a melt-affected ice core. Credit: British Antarctic Survey

Making sense of melting

For her PhD research, Moser has been working as part of a team to try to establish whether climate data can still be salvaged from melt-affected ice cores.

“We are in a crucial timeframe before the records are lost entirely,” she says. “I’m trying to understand whether and how we can still make sense of the information that we have.”

As part of her research, Moser has travelled to the Arctic to carry out experiments directly at the site of glaciers.

Moser carries out an experiment on top of an Arctic glacier. Credit: Iain Rudkin

During long days out in the field, Moser simulates the impact of meltwater on ice cores by introducing a liquid dyed with food colouring to the top layer of snow that sits above the glacier.

The blue colour of the food dye allows Moser to observe the path that the meltwater takes through the snow.

By comparing the snow composition before and after these experiments, Moser is also able to observe how the introduced meltwater affects the climate information preserved in the snow sample.

Moser examining the results of an experiment using blue food dye on snow. Credit: Iain Rudkin

The observations could one day help scientists to better understand the way that meltwater moves through ice and the impact this has on the particles that are present.

This, in turn, could help scientists tease apart the impacts of meltwater from the precious climate data still present in affected ice cores.

“I’m intent on showing that we can still make sense of this,” Moser says. “The melting of ice cores is a big issue and we need to raise the alarm – but we also can’t give up on them completely yet.”

Documenting rapid change

On board the boat that is drifting past chunks of ice that have carved from Blombstrandbreen – listening to the glacier melting drip by drop – the mood is sombre.

For her research, Moser constantly comes face-to-face with landscapes that are rapidly shifting because of human-caused climate change – an impact that she feels a duty to document, she says:

“Any scientific observation can have an emotional counterpoint. I’m researching this – and I am objective about measuring what I see – but I’m also feeling the changes.

“I have seen glaciers retreat. I have seen landscapes barren from the beauty they carried before. I think that has changed my outlook. It has made me think about whether climate change is a lost cause, or whether there is still hope. I think some people call that eco-anxiety.”

Despite this, she remains hopeful about the future.

“I think the work I do matters,” she says. “We are not powerless. There’s a deep urgency, but we have agency – and that makes me hopeful.”

Carbon Brief visited Svalbard in September 2024 with the support of the British Antarctic Survey.