In the Arctic Ocean, around 400 miles from the north pole, lies the island of Svalbard.

Named after the Viking word for “cold edge”, the island lay largely undisturbed before it was used as a base for whaling in the 17th and 18th centuries and transformed into a coal-mining hub in the 20th century.

Today, the capital, Longyearbyen, is a tourist destination. Further north, an international climate research station has been set up in the former mining town of Ny-Ålesund.

Ny-Ålesund hosts research institutes from a range of countries, including China, France, Germany, India, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and the UK.

Graphic: Carbon Brief. Credit: Norwegian Polar Institute (2014).

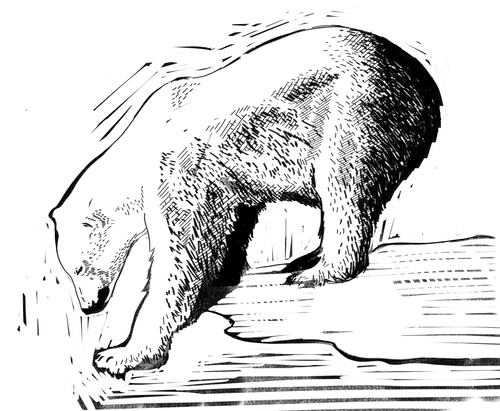

The town’s few buildings are near the coast, surrounded on one side by expansive wilderness hosting polar bears, Arctic foxes and reindeer. On the other are glaciers and fjords leading out to the Arctic Ocean.

This environment offers scientists a gateway to study how climate change is affecting the Arctic’s ice, ocean, atmosphere and ecosystems.

Svalbard is the fastest-warming place on Earth, with temperatures rising seven times faster than the global average.

In September 2024, Carbon Brief visited Ny-Ålesund to speak to a range of scientists from across Europe about the climate impacts they have witnessed and how it feels to live and work in the fastest-warming place on Earth.

What do you research here in Svalbard?

I’m an Earth scientist, specialising in ice-core science. My research is centred around making sense of melt-affected snow and ice records. In Svalbard, I am carrying out experiments to examine the percolation of meltwater in the snowpack.

What does a day in your life look like when you’re conducting field research?

My day starts the evening before, when I write in my notebook all the things I’ll need to do in the morning. In the morning, I get dressed, I pack all my equipment and also what I’ll need to sustain myself during the day. It is very cold. I will have to be prepared for -20 to -30C. I’ll definitely take a thermos. I try to take food that does not freeze. Ham in a sandwich doesn’t work, but peanut butter is still tasty when it is frozen.

We select our site for the day. When I arrive at the snowpack, I take all the measurements I need and then I’ll take some snow samples home. By that point, I’m probably pretty cold, so I’ll try to get home quite quickly, enjoy dinner and prepare for the next day.

Read more about Moser's research:

In-depth: How melting of Arctic ice cores threatens records of Earth’s past

For how long have you carried out research in the Arctic?

I started researching in this location in 2022, so two to three years. But I went to the Arctic in 2017 too, when I lived in Longyearbyen for four months to carry out university projects. So I started loving and being fascinated by the Arctic a lot earlier than my research.

Have you witnessed any climate change impacts in the Arctic that have shocked you or stayed with you?

The very first time I came to the Arctic left an impression. I arrived in February, which is the dark period and it should be really cold, but it was melting – in the middle of winter. So I was like: “This is not how it’s meant to be.” I was baffled and shocked because this was not the Arctic I was expecting. We couldn’t use the snowmobiles at first because we had to wait for the ice to refreeze. I think I have entered research at a time when climate change is not future, but present, in the Arctic. I’m working in a changing system, rather than having seen the before and after.

Melting glacier ice in Svalbard. Credit: Daisy Dunne

Has working in the Arctic changed your perspective on life?

I think, from an ice-core perspective, we have got massive ice mass loss. Where there was once ice, there is no ice anymore. So there is a sense of loss. Any scientific observation can have an emotional counterpoint. I’m researching this – and I am objective about measuring what I see – but I’m also feeling the changes. I have seen glaciers retreat. I have seen landscapes barren from the beauty they carried before. I think that has changed my outlook. It has made me think about whether climate change is a lost cause or whether there is still hope. I think some people call that eco-anxiety. But I’m still hopeful, I think the work I do matters. We are not powerless. There’s a deep urgency, but we have agency – and that makes me hopeful.

What is one thing you wish people in your country knew about your research, the Arctic or climate change in general?

I wish people knew that the Arctic is where polar bears live and the Antarctic is where penguins are!

With my research, ice cores are unique climate archives of the past and they are being affected more and more by climate change. That is causing us a lot of trouble, but it’s not a lost cause. My research is dedicated to trying to make sense of how ice cores are changing and how we can still best use them.

To hear more about Moser’s work at the UK’s Arctic Research Station, watch Carbon Brief’s recording of a webinar broadcast live from Ny-Ålesund in 2024.

What do you research here in Svalbard?

Clarissa: I work on permafrost research. I’m interested in modelling permafrost landscape change under climate change.

Anfisa: I’m helping Clarissa with her research. I’m also working in the field of biogeochemistry, mostly in mainland Norway. I’m hoping to study greenhouse gas emissions in a peatland area that is quite vulnerable to climate change.

What does a day in your life look like when you’re conducting field research?

Clarissa: One has to be very spontaneous here. The weather can change quite quickly and you have to be prepared for all possibilities and take opportunities when you can. We pack everything in the evening, have breakfast at 7.30am and try to be out in the field by 8.30am. Usually we come back after dinner. So we usually have lunch outside and a late dinner. It is just the two of us and we go everywhere by bike or on foot.

Clarissa and Anfisa work in Ny-Ålesund , the farthest north habitation in Svalbard. Credit: Daisy Dunne.

Anfisa: It’s only the two of us so we have to be responsible for each other in terms of polar bear protection. Usually, one person will do the job and the other will keep watch for bears. In Svalbard, you have to constantly think about polar bears.

For how long have you carried out research in the Arctic?

Clarissa: I have done research in the Arctic for five years now. It’s always exciting to come back. This is my first time in Ny-Ålesund.

Anfisa: I have done research since 2018. I have mostly worked in the Russian Arctic.

Have you witnessed any climate change impacts in the Arctic that have shocked you or stayed with you?

Clarissa: It is sad to see the velocity that the glaciers are melting. Just hearing them in summer breaking off and calving into the ocean. Knowing that this is a natural process, but also knowing that this is enhanced by us humans. Svalbard is the fastest-warming place in the Arctic. It makes me sad to witness it.

Anfisa: I have been working mostly with ground ice and it’s melting so fast. It’s the same with glaciers, it’s so visible. Every year you can see changes. In Yamal [in Russia], there are greenhouse gas-emitting craters. They look really scary, like a big hole in the ground.

Has working in the Arctic changed your perspective on life?

Clarissa: Yes. It’s a very rough environment. It makes you prioritise differently. It makes you be very present and makes you realise that you should make plans, but life is going to happen and you have to be spontaneous and change plans. You need to be strong and independent, but you’re only going to get so far alone. It’s always a team of people making things possible here.

Anfisa: I think so. In the Arctic, everything depends on you and a small group of people. You need to be honest with everyone and with yourself. Be careful and polite, not only to people but also to nature. If you see a polar bear, you have to be extra polite.

What is one thing you wish people in your country knew about your research, the Arctic or climate change in general?

Clarissa: I think most people know what climate change is and what it would take to act accordingly to prevent the worst from happening, but I think the emotional connection is lacking. I think it is very valuable for people to see how vulnerable and beautiful the Arctic is and how much we should take care of it. But on the other hand, the typical trips for people to experience it are not exactly climate friendly. So I don’t have a solution for that myself. But I guess carrying out outreach through our research and social media can help people relate and eventually create an emotional connection to change behaviour.

Anfisa: In the Arctic, there are Indigenous people who live there. I would love people who do not live in the Arctic and who are not familiar with the culture of these people to become more familiar and listen to them more carefully. Especially when we are talking about Russia. Russia is so big and the Arctic zone is massive. Everyone should be familiar with the conditions Indigenous people live in [in Russia] and how climate change is changing their lives.

What do you research here in Svalbard?

I have a 10-year experiment in a place called Kongsfjordneset [a headland in Svalbard]. The aim of the experiment is to warm up plants and soils to see how they respond to about a degree increase in temperature over 10 years.

What does a day in your life look like when you’re conducting field research?

Hectic. You have to get up at a very small hour to get food because the Norwegians eat early. And then generally you work all day and, if you’re not reliant on other people, you’re working all weekend as well. Last week, for example, I did a 15-hour day, which is quite challenging. But it’s interesting work and people are all here for the same reason so it’s not too difficult. We go out to the experiment site by boat, otherwise it would be a nightmare because it’s 11km to walk back.

For how long have you carried out research in the Arctic?

I have been coming to the Arctic since 2012. I had a couple of years off during the pandemic, so I have come for 10 years in total. Prior to that I worked in the Antarctic, on Alexander Island, where I had a similar experiment, but the effects of climate change on the glacier meant the planes could no longer land on the glacier that was near the experiment, so we essentially lost a field site.

The author (top left) visited Svalbard in 2024. Credit: Daisy Dunne.

Have you witnessed any climate change impacts in the Arctic that have shocked you or stayed with you?

Yes, I suppose so. I do know people who worked here in the early 90s, around 30 years ago, and they told me it was very cold in the summer and it mostly snowed. Whereas now, it mostly rains. It’s supposedly a high Arctic semi-desert here in Svalbard, but it rains a lot now.

There was an avalanche in Longyearbyen in 2015. It killed three people. When you go to Longyearbyen now, you can see a load of fences to stop avalanches coming down the hillside from the top of the mountain.

Has working in the Arctic changed your perspective on life?

Crikey, I don’t know. There’s certain situations where I’m more confident than I was. For example, if encountering local wildlife, such as polar bears, I think I can give it a reasonable shot of dealing with the situation rather than screaming and running away.

The most recent time I encountered a polar bear was 2019. A bear was wandering down the beach, but luckily it was spotted by Nick Cox, the manager of the UK base at the time, while it was still a long way off. If he had not spotted it, it would have been walked between us and our boat, which would have been quite a dangerous situation.

What is one thing you wish people in your country knew about your research, the Arctic or climate change in general?

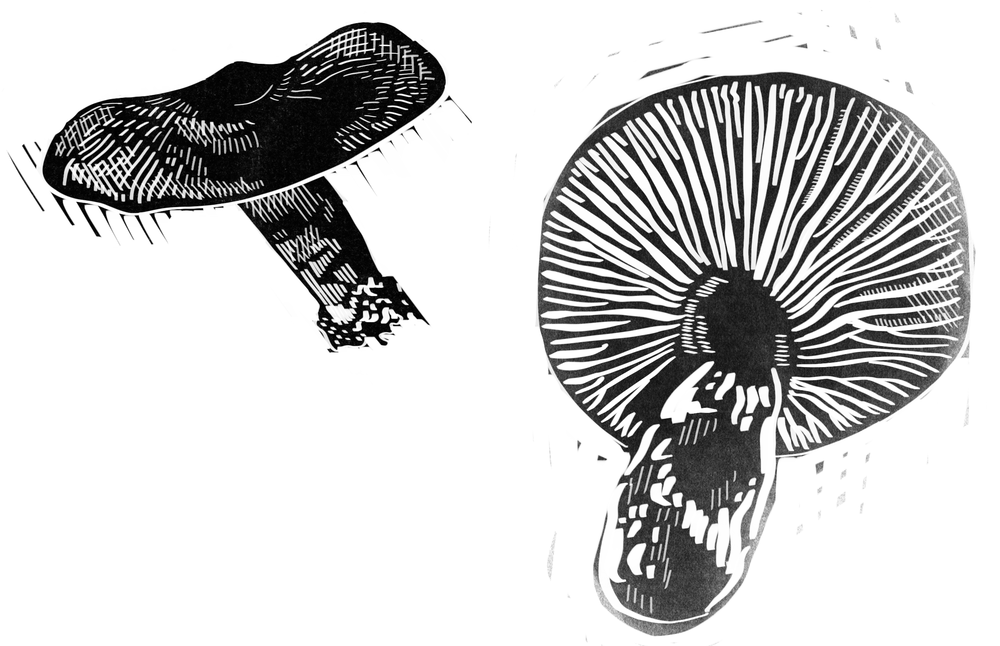

I think probably the one thing I’d really like people to appreciate is the importance of fungi. I study fungi, and I don’t think most people really appreciate how important they are in the natural environment, because they are invisible. For the most part, you do see macroscopic toadstalls in woodlands. But in a gram of soil, there’s enough fungal hyphae – very fine strands that are maybe two-hundreths of a millimeter in diameter – to fill a few kilometres if laid out end to end. They are super abundant in the natural environment, but nobody really understands what they do.

What do you research here in Svalbard?

I am doing a year-round survey to see how climate change affects polar cod. These little fish are very important in the Arctic Ocean. They are what we call a keystone species. That means that, in its place in the food web, there are no others. Everything that is bigger eats it and everything that is smaller gets eaten by it. There has been a lot of research into what climate change does to them, but never really in an exercise kind of way. So I’m asking whether warmer waters affect their ability to exercise or swim through the ocean.

What does a day in your life look like when you’re conducting field research?

I wake up at 6 or 7am and then I go to check on my fish. I check that they are doing okay, if they’re swimming, if they’re having fun. Then I prepare them for their exercises. I put them in a swim tunnel and then I let them get used to it for a bit. Then I need to do some calculations. They are a certain size and I have to take that into account when I do my experiments. Then I eat breakfast. After breakfast, I start my experiments. That is when I start increasing the speed in the swim tunnel and see how long they can swim at a comfortable pace. Right before lunch, I let the second group of fish chill and hang out in the swim tunnel. I also help my colleagues, for example by going out and collecting water samples from the fjords. In the evening, I sometimes keep on with my experiments.

For how long have you carried out research in the Arctic?

This is actually my first time. This is my fourth week. Before this, I was working on African crabs. So this is really my first foray into the Arctic.

Have you witnessed any climate change impacts in the Arctic that have shocked you or stayed with you?

On a professional level, not really yet. But, when I decided to become a marine biologist, I was actually on vacation in Svalbard. That was six or seven years ago. Then I saw the glaciers and they were magnificent. And then, this year, I went back to the same place and I saw they had already retreated. I saw rocks that I couldn’t see before. To see that with my own eyes, I thought: “Oh s**t, this is really going quick.”

Has working in the Arctic changed your perspective on life? How?

Yes, it really has. Especially because of these little animals that I work with. Every little animal counts. Every little animal is important for something. If you scoop up a handful of water and all you see is tiny crustaceans, they are food for another animal and that animal is food for a polar bear. All these little things affect each other. This is something you only really realise if you see it with your own eyes. How important it is to take care of one little species, even though it might look boring to some people.

What is one thing you wish people in your country knew about your research, the Arctic or climate change in general?

Most people say: “It’s so out of sight, it’s so far away.” For people in the Netherlands and in Germany, it’s far away, so they think it doesn’t really matter. But things that happen here all cascade down to [all of] us. We have these huge ocean currents that connect us to the Arctic. If the warm water is up here, it also comes down. So what happens here is important to us. This is what I really hope to convey to as many people as possible, because I have seen it with my own eyes.

What do you research here in Svalbard?

My research is soil ecology with a focus on microbes, but also larger fauna, including nematodes and different protist groups. And what we’re doing here is essentially studying, or trying to anticipate, the effects of future climate change on these organisms – both [in terms of] their presence and also their activity. We do this through molecular techniques mainly. We estimate how they will change in the future based on increased temperature and increased soil moisture, the two main things changing in the Arctic.

What does a day in your life look like when you’re conducting field research?

Long, but really amazing days. Usually we have one field trip a day, sometimes two. Depending on the weather conditions, we can take the boat out to further sites. Otherwise we bike up to nearby sites. We then take stick soil samples. It’s usually sterile conditions, which means we need to use ethanol all the time, with our gloves, on our boots, on our bags, which can be tricky if you’re working in rainy, windy conditions. Then it’s just a process. Usually we create a little chain of handling things that need to happen. One person takes a sample, one person sterilises the bag, the other one sub samples and so forth. Given the weather conditions, we try to work quite fast. In a day of 14 hours of work, I would maybe be in the field for four or five hours. People also get cold and wet. Especially now it’s late summer, it’s really wet.

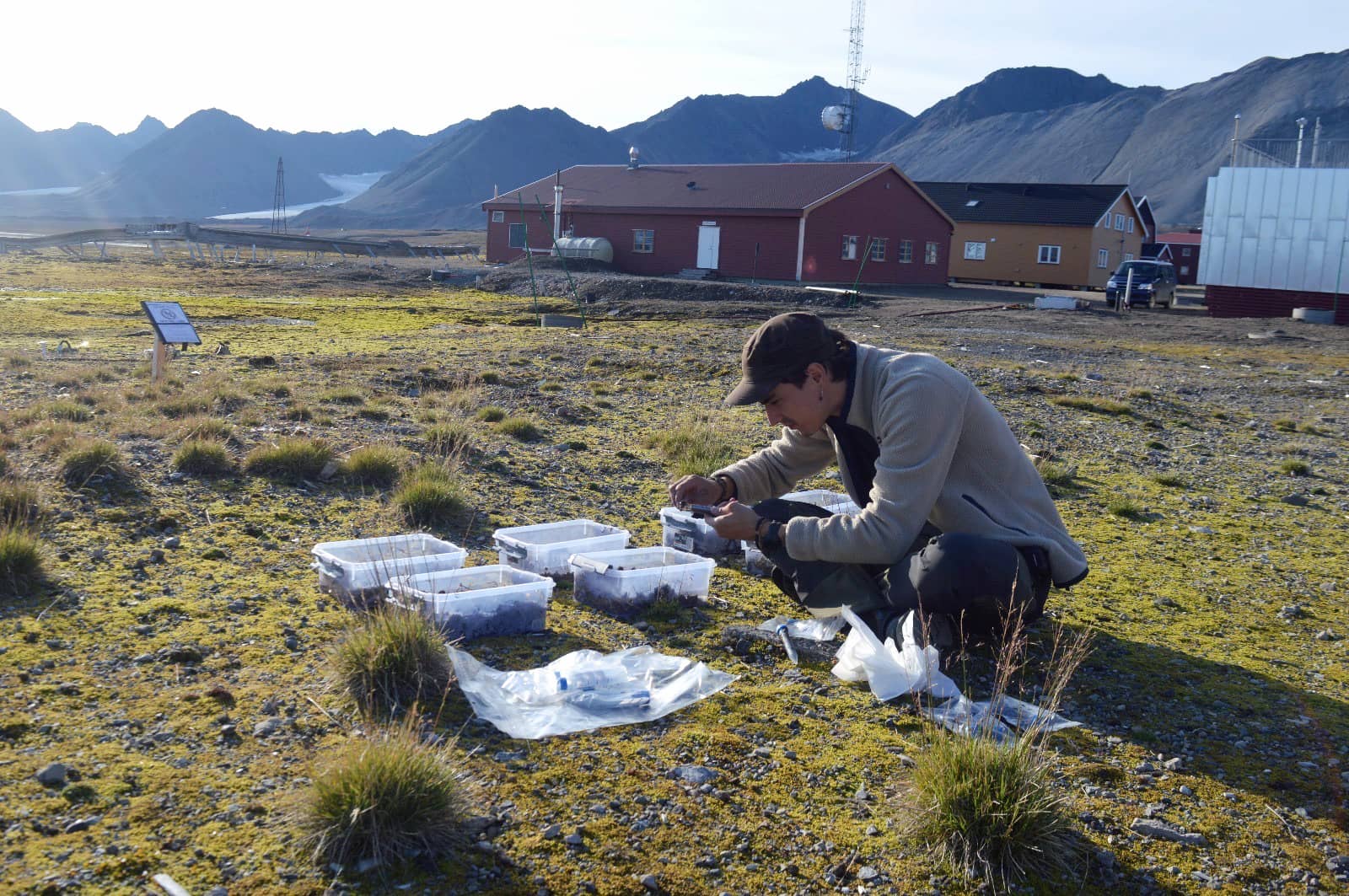

Ruben collects samples in the field. Credit: Ruben Van Daele.

For how long have you carried out research in the Arctic?

Two years ago, I worked in northern Norway, that’s sub-Arctic. This area, high Arctic, I only arrived here a week and a half ago.

Have you witnessed any climate change impacts in the Arctic that have shocked you or stayed with you?

My parents figured I would be working in the snow. In the north pole, they think it’s snowy and icy all the time. Of course not, especially with the warm water coming in from the fjords. But I think the peaks are supposed to be more icy. I’ve noticed a lot of glaciers melting. What I’ve noticed – and I think this is the scariest – is the brown water in the fjord system. You can clearly see how the different glaciers are eroding and losing their mass and casting dirty soil and debris into the water. It is really changing such huge surface areas of this fjord system. That’s a very clear change you can see today.

Has working in the Arctic changed your perspective on life? How?

Oh it has, that’s the funny thing. I have always loved field work, I’m not a lab person. It’s why I’m an ecologist, so I can go out in the field as much as possible. It’s really fulfilling to me. I’ve always seen myself going to the south, to the warmer areas. Belgium is not the best climate. But, I must say, since being here in the Arctic, I’ve been really enjoying myself – even with the 12-14 hour days just labelling things in the mud and the rain. I could see myself moving north instead of south.

What is one thing you wish people in your country knew about your research, the Arctic or climate change in general?

On climate change in general, it’s way more noticeable here. [The Arctic] is sort of a proxy for us because it’s warming way faster than other areas. People back in Belgium may not see the effects of climate change around them that much at the moment, but here it's already really visible. If I could show them what's happening here already, what I'm seeing, what I'm doing, what people here for years already have been seeing, that I would love to do. If they could actually see the imminent dangers and real effects already, I could warn them and say: “Hey guys, back in the south, we’re not safe there.” The sea level is rising. Belgium is very low and flat. We’re going to lose a lot of surface area. I would love to warn them about that.

All answers have been edited for clarity and length. Carbon Brief visited Ny-Ålesund with the support of the British Antarctic Survey.