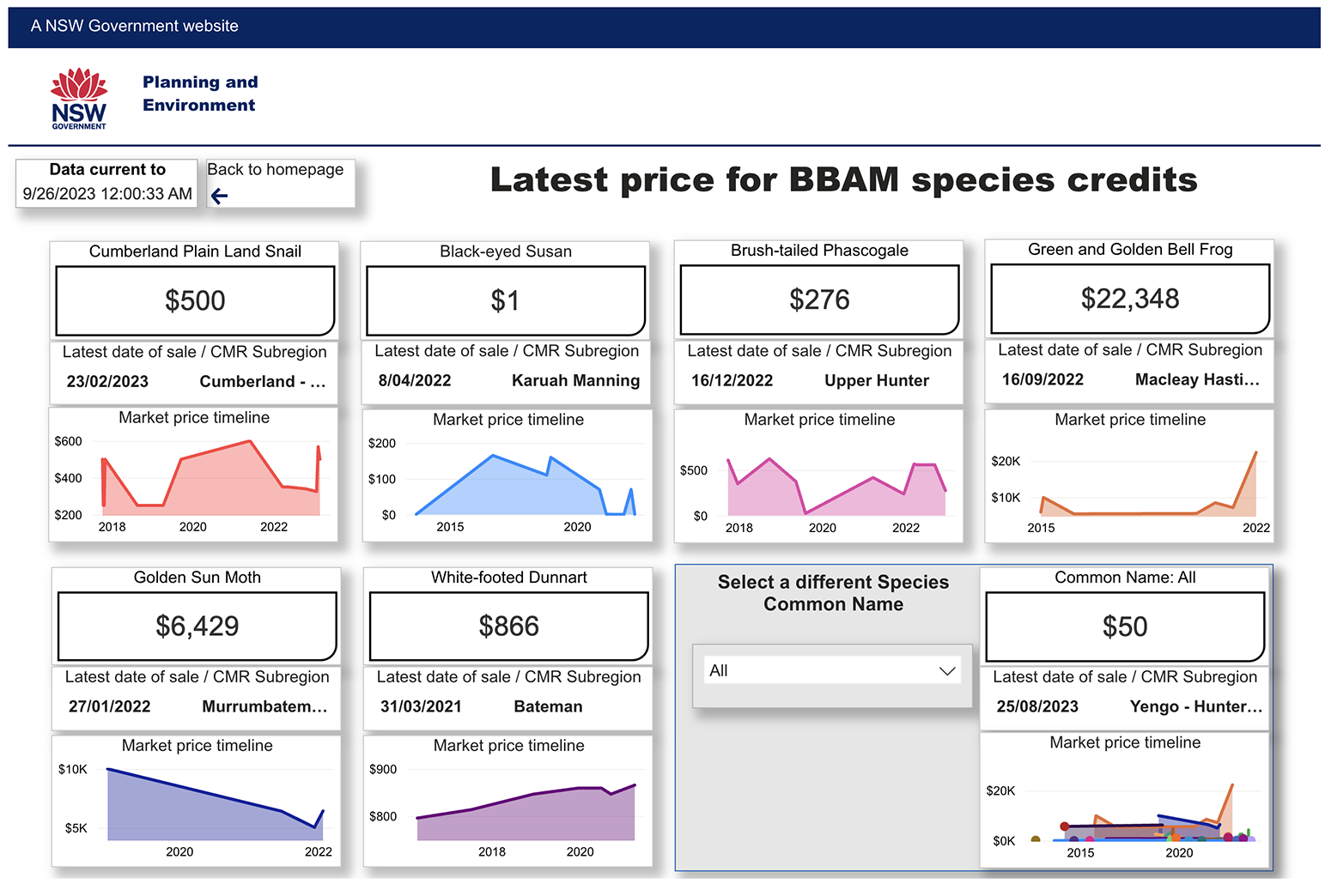

In recent years, “biodiversity offsets” and “credits” have been promoted as one of the key ways to finance nature conservation and support global biodiversity goals.

Put simply, “biodiversity offsetting” is a system for placing a value on a habitat, plant or animal, meaning the “credit” or “unit” can be bought or sold to “offset” damage being done, thereby creating a financial incentive to conserve natural assets elsewhere.

Biodiversity-rich developing countries have been demanding more public finance and “debt forgiveness” from developed countries – which is distinct from climate finance – to help meet their biodiversity targets.

This article is part of a week-long special series on carbon offsets.

Meanwhile, rich countries, such as Australia, the UK and France, have been promoting and rolling out new “nature markets”, claiming that conservation budgets are stretched and that private finance must play a more prominent part in closing the finance “gap”.

Biodiversity offsetting now sits at the heart of these tensions.

“Until now, we were doing development without any due regard for biodiversity,” Prof David Hill of the UK’s Environment Bank tells Carbon Brief. He argues that regulation-backed biodiversity markets could “provide a pressure valve by which finance can be generated [for] proper biodiversity restoration”.

Critics of offsetting disagree. “These metrics are quite simplistic, mechanistic and crude,” Dr Evangelia Apostolopoulou of the Autonomous University of Barcelona and the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership tells Carbon Brief. “What you need to actually question is the very idea of the economic valuation of nature.”

While biodiversity-offset markets have so far escaped the intense criticism that carbon-offsetting has been subjected to, they are growing in prominence and were included as one of the ways to finance a global deal for nature agreed at the UN’s COP15 biodiversity summit last year.

(Clicking links with a will display the full glossary term.)

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief breaks down the history of biodiversity offsets, where and how they are being used around the world and concerns surrounding their use.

What are biodiversity offsets?

Biodiversity offsets are defined as conservation activities intended to compensate for the lasting impacts of development on species and ecosystems that persist even after other mitigation measures.

These offsets are built around the idea of “no net loss”.

This is an assumption that damage to ecosystems wrought by large-scale development projects – from mining and industry through to highways and land-use planning – can be balanced or outweighed by “producing” or preserving nature elsewhere.

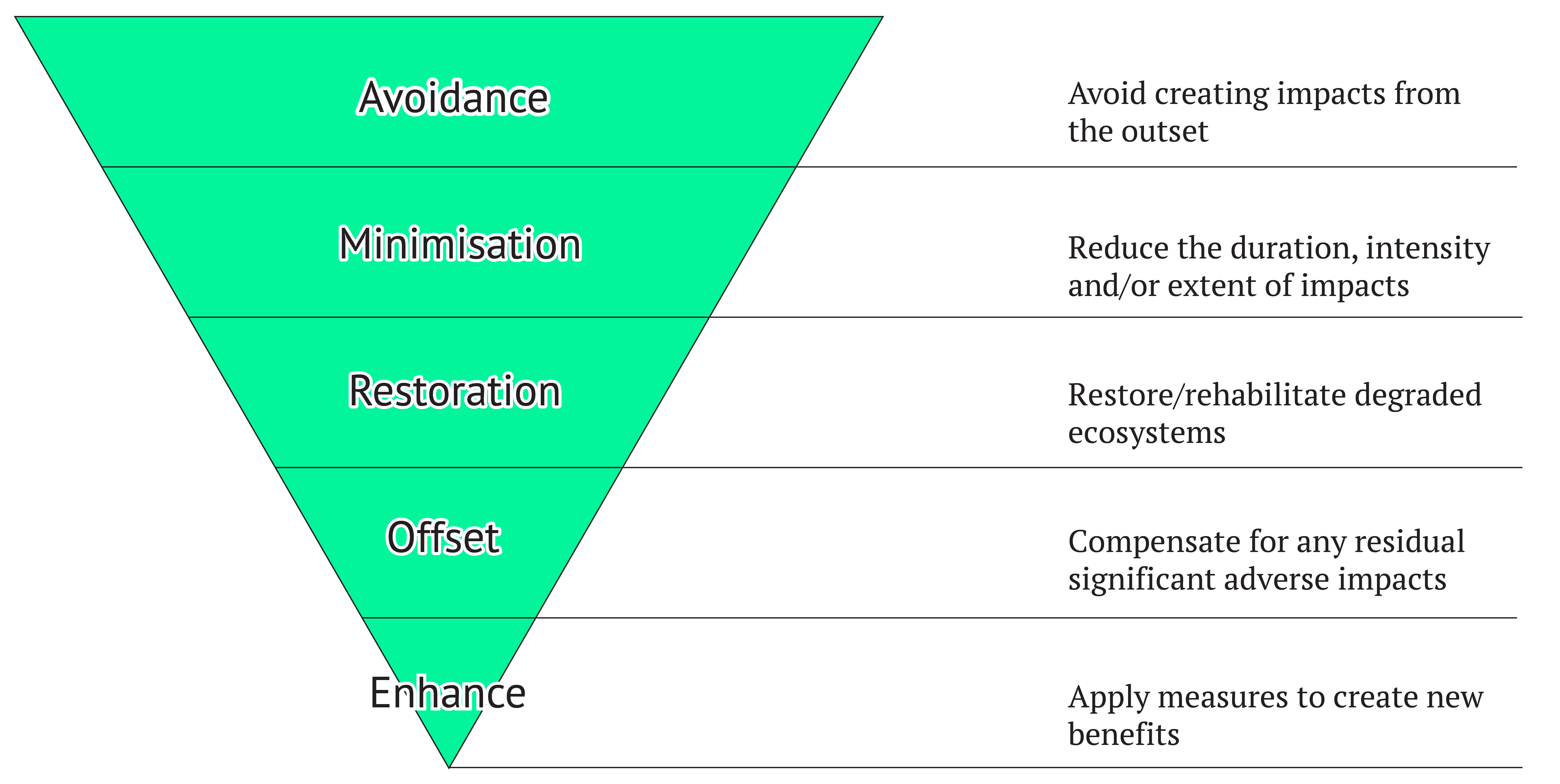

In theory, biodiversity offsets are deployed as the last stage of what is called the “mitigation hierarchy” – a set of five principles (pdf) to adequately respond to negative impacts on biodiversity from development and to ensure no net loss. As defined by the UN Environment Programme and the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, these steps are:

- To avoid negative impacts where possible.

- To minimise impacts, if necessary.

- To restore and rehabilitate the environment.

- Only then, to offset unavoidable and necessary harms through compensatory conservation actions.

- To accrue benefits to the environment over time.

The diagram below presents different stages of the mitigation hierarchy and states when offsets should be applied to ensure no net loss.

Advocates of offsetting believe that conservation actions can also yield net-positive outcomes, whereby biodiversity increases overall year-on-year – a concept known as “biodiversity net gain”.

Closely related to the concept of biodiversity net gain is what is known as “nature positive”, which many liken to a “net-zero” target for nature. “Nature positive” is a much wider process that incorporates aspects of nature beyond just biodiversity gain, such as climate mitigation. However, the term and its metrics are yet to be comprehensively and credibly defined, despite its increasing use.

Some proponents make a distinction between biodiversity offsets and biodiversity credits.

Sign-up to Carbon Brief’s award-winning newsletters here

According to the Taskforce on Nature Markets, an initiative led by a coalition of financiers, entrepreneurs, academics and conservation groups, biodiversity offsets aim to compensate for direct or indirect impacts on ecosystems from development projects. By contrast, biodiversity credits are not necessarily linked with specific ecological damage. Instead, they can contribute to conservation directly.

Critics tell Carbon Brief that they disagree with this framing of biodiversity credits as being a “positive contribution” and any different from offsets. They question the motivations of investors who purchase such credits and ask whether they would want to buy them if they could not be used to make a “nature neutrality” claim. (See: What are some of the main criticisms of biodiversity offsets?)

In the case of carbon, some choose to make a distinction between offsets and credits based on the marketplace they are traded in and whether they are mandated to deliver on emissions cuts.

When emission cuts are mandated by law, companies buy carbon credits from a compliance marketplace to meet their binding emissions targets. However, when there’s no such legal “cap” on emissions, companies and individuals are free to buy offsets from voluntary carbon-markets, which involve much less scrutiny. (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A on carbon offsets.)

For biodiversity, the only stated difference between offsets and credits is in their intended use and not in the marketplace. Currently, biodiversity offsets are traded in both compliance and voluntary markets, while credits are only traded in voluntary markets. But this could change with a new wave of government-backed credit markets. (See: Where do biodiversity offsets fit into national and international policy and are they gaining traction?)

Polly Hemming, climate and energy director at the Australia Institute thinktank, says it is unclear where the demand for biodiversity credits is going to come from, other than offsetting. She adds:

“If we look at the voluntary carbon market, companies are buying carbon credits voluntarily, but they’re using them to make an offset or carbon-neutral claim. There is no evidence that people are going to be buying biodiversity offsets unless it is to offset some damage. So there’s no evidence that there is a market beyond financial proponents and people who want to believe in promoting the trillions of dollars that a biodiversity market could be worth.”

Where did the idea of biodiversity offsetting come from?

Academics and analysts see biodiversity offsets as part of a push to privatise and commodify nature, using market-based mechanisms to solve environmental problems instead of state regulation. It is the latest chapter in a long history of debates that have seen the environment pitted against development.

According to Dr Yung En Chee at the University of Melbourne, biodiversity offsets arose from the concept of “ecosystem services”, namely, placing a “value” on what nature provides to society. First used in the 1960s, efforts to illustrate the connections between nature and society were followed by a “march” towards commodifying nature. Chee tells Carbon Brief:

“[It] creates a new frontier. We’ve gone from talking about these links conceptually – and using them to illustrate the actual value of nature – to thinking: ‘Well, how can we compartmentalise these things and use them to pay their own way?’”

The ideas and policies around biodiversity offsets are thought to have emerged in response to “radical” discourse and literature in the 1960s – such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring – that questioned the paradigm of endless growth and, while pointing to planetary boundaries being rapidly breached, called for hard limits to economic development and pollution.

The mitigation hierarchy and ideas around compensating for biodiversity loss were first introduced in conservation legislation in the US in the 1970s, as part of a growing move towards market-based mechanisms.

The idea of “no net loss” was first applied to mitigating wetland loss in the US in the 1980s. It influenced the development of a commercial wetland mitigation banking system – a market for wetland ecosystem services – to meet the goals of the Clean Water Act.

In Europe, concepts of compensation and offsetting damage had already been enshrined in several countries’ laws aimed at reducing deforestation. Germany’s Federal Nature Conservation Act in 1976, for example, required that any habitat facing significant damage from human intervention “has to be offset”.

Meanwhile, emissions trading in the early 1990s and carbon-offsetting, especially after the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, led to greater policy acceptance of offsets and market-based environmental regulation across the world.

The Australian states of Victoria and New South Wales were the first jurisdictions to introduce biodiversity-offset markets. In 2002, Victoria’s Native Vegetation Framework introduced a measure called “native vegetation offsetting”, where land clearers could buy credits to offset their impacts on native plant species. The first offsets implemented under the framework entered the system in 2006.

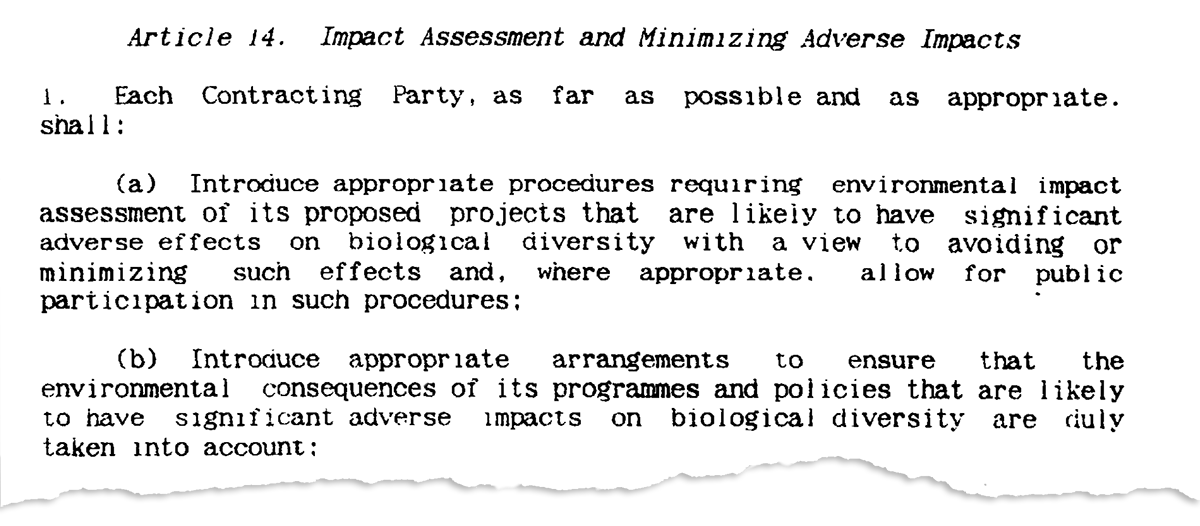

On the international stage, the ratification of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in the early 1990s provided stronger safeguards. Prevention, minimisation and compensation were officially part of the text, with the aim of “halting biodiversity loss”. The convention set and influenced national standards for including biodiversity in national environmental impact assessments. It also made mitigation hierarchies the norm and served to erode the legitimacy of extractive industries.

Buoyed by this, conservation organisations, such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), developed strong positions supporting “no-go” zones, starting in 1998, to limit extractive activities in protected areas. This saw strong pushback from the mining industry, although campaigning achieved limited success in securing no-go commitments from industry for keeping its activities outside of World Heritage Sites.

Industry consortiums, such as the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), and corporations, such as Shell and Rio Tinto, began engaging and “partnering” with conservation organisations, including IUCN and the Nature Conservancy in the early 2000s. Miners argued that “no-go” zones were too “rigid”, but said that land-use management, voluntary commitments, offsetting and restoration were within their industry’s reach.

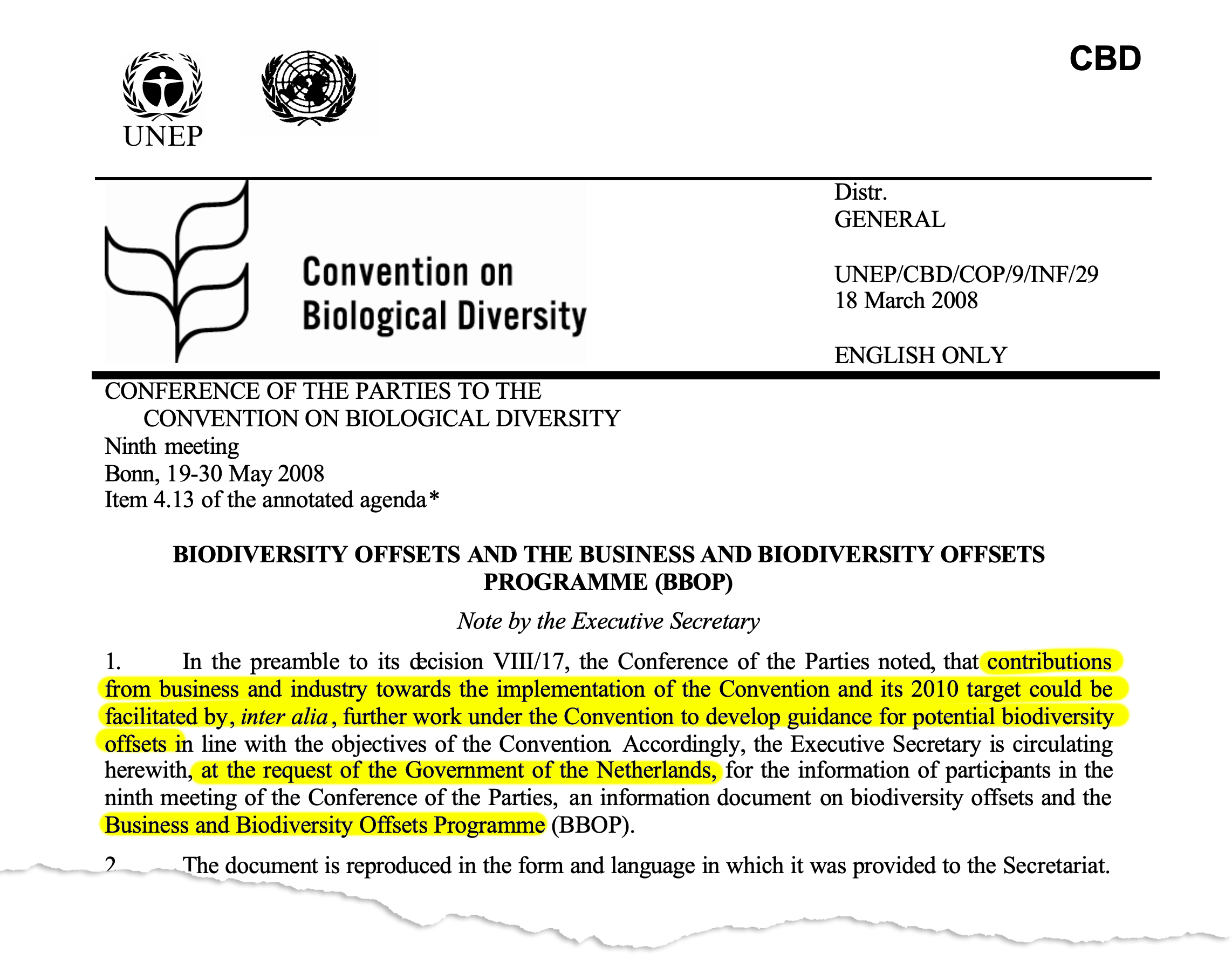

In 2004, the US-based NGO Forest Trends established the Business and Biodiversity Offset Programme (BBOP), a transnational coalition of 40 conservation organisations, companies, financial institutions and government agencies working to establish development projects that did not lead to a net loss in biodiversity.

The group became extremely influential in advocating biodiversity offsets as a policy within the CBD, especially as European government agencies increasingly got on board.

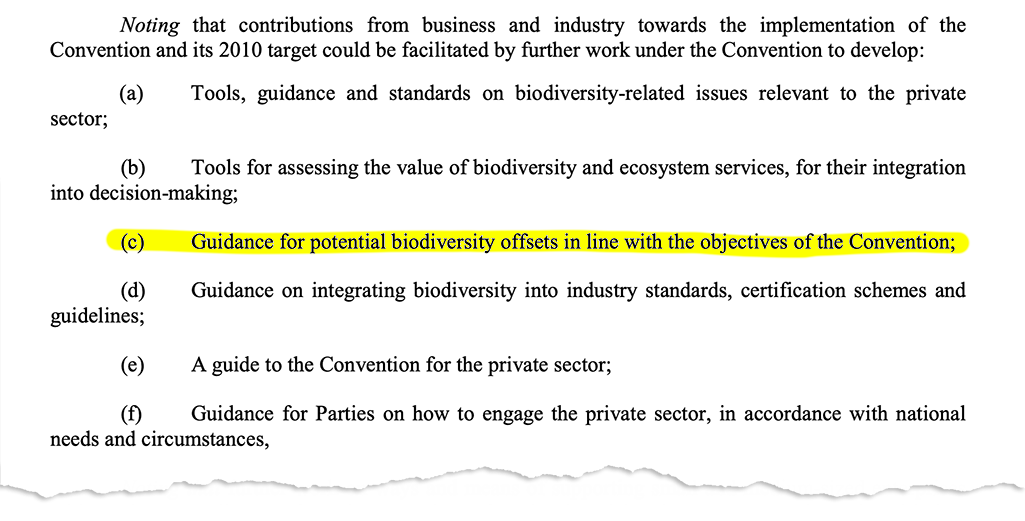

In 2005, the CBD’s Conference of the Parties (COP), its governing body, issued its first standalone “cover decision” on private-sector engagement and considered developing guidelines on biodiversity offsets to meet 2010 biodiversity targets. Cover decisions are important political overview decisions, agreed by all countries, that can give issues a place, even if they do not appear elsewhere in official negotiations.

By 2018, BBOP’s 130-member-strong advisory group included Shell, miners Anglo American and Rio Tinto, the International Finance Corporation, Citi and WWF. It began drafting principles and good practices for offsetting.

At COP9, the CBD circulated a 50-page document, prepared by and in conjunction with the BBOP, outlining these draft principles below.

The CBD started to conduct workshops on biodiversity offsets as part of “innovative financial mechanisms” to bring in funding for climate change and biodiversity. In 2010, the CBD’s COP agreed to promote offsets as a way for businesses to mitigate their impacts.

By 2016, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated that there were around 100 biodiversity-offset programmes operating worldwide.

Additionally, at least 56 countries had laws and policies that specifically required biodiversity offsets, or some form of compensatory conservation, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Mexico, New Zealand and South Africa.

How do biodiversity offsets differ from carbon offsets?

Biodiversity offsets and carbon-offsetting are similar in that they exist for polluters to compensate for damage they have done.

But there are significant differences.

In the case of carbon offsets, polluters tend to buy offsets to compensate for their emissions on an annual basis. But biodiversity offsets and credits typically involve longer contracts, since biodiversity losses and gains occur over much longer timescales. Gains in biodiversity are also less predictable, making it more difficult to meet year-on-year goals with a conservation offset than, say, a solar farm.

Carbon offsets can be generated from a range of different sources that promise reductions in emissions, including both technical projects, such as renewable energy, and nature-based ones, such as tree-planting. (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A on carbon offsets.) Conversely, biodiversity offsets can only be created by people contributing to conserving or restoring ecosystems.

Unlike carbon offsets, biodiversity offsets are tied to specific development projects and the impacts on specific habitats and species. Companies, for instance, can invest in trying to create forest habitat elsewhere for a particular species displaced by their activities.

In contrast to carbon markets set up under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), there is currently no international marketplace for buying and selling biodiversity credits or offsets. Countries cannot currently trade their own biodiversity “outcomes” to help other countries meet their biodiversity targets.

Ecosystem changes involve a multitude of interactions. Therefore, monitoring and verifying biodiversity changes and being able to attribute them to any one intervention is harder to do – and a lot more expensive. Transaction costs – or the labour of bringing a good to a market and delivering on it – are also much higher in biodiversity-offset markets.

According to Hemming, this is one of the reasons why biodiversity-offset market “goes against the most basic market theory”. These markets will be plagued by the same “integrity” issues as carbon markets, if not worse, she adds. Hemming tells Carbon Brief:

“Investing in something that has inherently high transaction costs – in terms of setup and measurement and monitoring and evaluation – means investment is similarly costly. The only way around those costs is when standards for evaluation, monitoring and enforcement are relaxed, which, of course, leads to credits that are affordable, but they’re of low integrity.”

How does biodiversity offsetting work and how is ‘nature’ quantified?

Every biodiversity-offsetting scheme, policy or market is different, but there are similarities in how each is developed.

First, they need to define a “threshold” that spells out when and at what stage a biodiversity offset is appropriate. Many countries have their own mitigation hierarchies in environment or wildlife laws that dictate when offsets can be used. But they might also have a list of regions or species that are “inviolate” – those that must be protected at all costs.

Biodiversity offsets are widely deemed to be improper by many national policies, for “critical”, “endangered” or “non-substitutable” biodiversity, such as in South Africa. But what is viewed as irreplaceable or “high-value biodiversity” has to be clearly defined and identified by those policies. For example, IUCN’s policy on biodiversity offsets observes that “it is not possible to offset the global extinction of a species”.

The next stage is assessing the biodiversity present at both the development site and the offset site.

Valuing biodiversity is extremely difficult because of how complex and unknowable any ecosystem is, plus the fact that no two places on Earth are alike. Many offset schemes today circumvent this complexity by focusing on specific species or habitats, rather than attempting to value all the species within a habitat.

To determine the value of biodiversity, policymakers use one or more of three measures: area; a composite “biodiversity metric”; and economic valuation of costs and benefits.

According to Dr Sophus zu Ermgassen at the University of Oxford, there are “a million different ways” of doing biodiversity metrics, ranging from basic measures to bespoke metrics, but “it depends, ultimately, on what you value from nature and what is practically feasible”.

For instance, “area” is central to England’s biodiversity metric, zu Ermgassen says, which is a calculation based on size, conservation importance and ecological condition of the habitat.

Large extractive projects often use “bespoke” approaches which let them harm some aspects of biodiversity, but “make sure…specific aspects of diversity” are not harmed, zu Ermgassen says – for example, mining projects that calculate and attempt to offset the impact on endangered species such as chimpanzees.

Ethnobotanist Madhu Ramnath believes it is “difficult” to see how offsetting could work in biodiversity-rich developing countries such as India, “since there is seldom any stocktaking of what we are going to lose before we destroy a place for mine or a dam”.

Ramnath, who is part of the Non-Timber Forest Produce Exchange Programme, tells Carbon Brief that most of the environmental impact assessments he has seen are “compromised” and reduce dense forests to scrubland, justifying their clear felling for industry. Even in an ideal world, the metrics are “doubtful”. He elaborates:

“To understand plant diversity in a forest patch, we use species-area curves: the maximum number of species in the minimum area can kind of tell you about the biodiversity of that zone. In similar forest types, if you can find similar species-area curves, you can perhaps assume that plant diversity may be similar.

“But how many species are we going to map? Just the flowering plants? Do we include all the ferns? What about fungi and underground species? It’s almost like measuring rainfall, with the data confined to the amount of rain. A 100mm here and 90mm here is recorded, but little about the time it took and the force it came with and how that filtered through ecosystems: all those things matter.”

Ramnath spent 30 years living and working alongside the Durwa Indigenous people in the state of Chhattisgarh, helping them map their traditional knowledge of local biodiversity while also growing native species for restoration of degraded forests. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I think offsetting will be very bland. It will be a numbers game. But it will not have the same quality of understanding these interactions that most Indigenous peoples have.”

According to zu Ermgassen, while there is a “large ‘innovation ecosystem’ developing biodiversity metrics to be applied to global or local scales”, there is also research emerging showing that “changes to some of these metrics do not correlate with changes in the real world”. He adds:

“We’ve created a way of measuring something that might actually not really correspond to the thing that we want to measure, but it’s measured in that way for specific convenience…In many cases, the ways of measuring biodiversity are not empirically tested.”

After countries and developers decide on a metric, the next stage is determining the “equivalence” of the offset site to the development site.

Chee points out that “equivalence” is a really difficult concept when it comes to biodiversity.

“With carbon offsets, a tonne of CO2 is still a tonne of CO2. But because of its complexity, biodiversity can’t be reproduced in its exact form somewhere else.”

Usually, it is agreed that biodiversity offsets should be on a “like-to-like” basis, where biodiversity conserved is equal to biodiversity lost.

Where this is not possible or appropriate, offsets are sought around the conservation needs of a particular species or habitat. Some policies promote a third option, which is “like-for-like-or-better” – also described as “trading up” – offsets, where harm to species of “lesser value” is compensated by protecting species or ecosystems that are of higher conservation priority.

According to the World Bank’s 2016 offsetting guide, however, trading-up compensation funds “are not real biodiversity offsets” because the conservation actions they support “do not necessarily involve the same ecosystems or species that were harmed under the original project”.

Another critical stage is to determine where to locate the offset site. When this is done in an area that is far away from the site of the damage, benefits might not go to the community that was harmed. This is why there is a strong rationale that offset sites should be located in the same watershed or biogeographical region. However, developers have argued that this is not always feasible, claiming that locating offsets elsewhere can result in greater biodiversity benefits.

Timing offset projects is another concern, given that time lags between an impact occurring and an offset gain could also cause damage. According to IUCN’s policy on biodiversity offsets, “the offset should be in place before the impact occurs”.

Finally, developers must ensure that there is additionality or no overall net loss, which means that they must prove that conservation actions would not have taken place in the project’s absence and the damages have been remediated. This necessitates effective monitoring, evaluation and managing uncertainties.

What are some of the chief criticisms of biodiversity offsets?

A persistent and widespread critique of biodiversity offsets is that they reduce complex lifeforms to a tradeable statistic, devoid of any inherent value. This can “crowd out” people’s intrinsic motivations to conserve nature.

Another criticism is whether there should even be a market for a public good, such as biodiversity (See: Are biodiversity offsets a reliable and predictable source of finance for conservation?).

Policy experts fear that biodiversity offsets are primed to repeat the mistakes of 30 years of experiments with carbon markets which have seen problems with environmental integrity, additionality, permanence, leakage and transparency. (See: In-depth Q&A: Can ‘carbon offsets’ help to tackle climate change?)

By comparison, Hemming warns, the risks for both nature and investors are “much, much worse”.

Monitoring, environmental integrity and additionality

The main challenges zu Ermgassen identifies in his analysis of biodiversity markets are: bad methods and metrics; poor compliance and governance; and a need for a substantial investment in monitoring and governance. Such investment is crucial “to make sure that the thing that you’re buying is really delivering an increase in biodiversity like you think it is”, he says.

While methods for monitoring and governance have progressed in recent years, implementation is expensive.

To develop robust biodiversity-offsetting markets, zu Ermgassen tells Carbon Brief that it is “fundamentally essential, from a scientific perspective”, to track the change in outcomes between a site that received investment and a control site that received none.

For instance, in a study evaluating the outcomes of a biodiversity-offsetting system in Australia’s Victoria state, his team found that vegetation cover did increase after offsets were implemented. But, compared with control sites, this growth was not actually more than that found everywhere else because the state saw significantly more rainfall in that period than in previous years during the “millennium drought”, leading to vegetation recovery across the state.

Unless markets can ensure rigorous procedures to detect non-compliance, they could fail conservation outcomes. But better compliance is costlier and exposes investors to the liability of knowing that the project they paid for is not working, says zu Ermgassen. He elaborates:

“In order for markets to work, we need a huge amount of investment in quite expensive governance. And there are potentially quite strong vested interests against that kind of investment. In essence, we’ve created a system where there’s a perverse incentive not to know if you’re wrong because then you get exposed to the liability that you paid to get rid of in the first place.”

There are also attempts to package up carbon and biodiversity as a single product – something called credit stacking.

This raises the possibility that someone purchasing a biodiversity credit is paying for something that has already been paid for as a carbon credit. Chee tells Carbon Brief:

“We can try and separate them and do the accounting, but, in reality, this is incredibly difficult to untangle…It’s not an honest product.”

A growing claim from governments is that offsets and biodiversity-offsetting markets are essential because there is no money in state coffers for conservation. Hemming says:

“In Australia, our government has gone as far as to say it can’t afford to do the job alone, because biodiversity conservation will cost around $1bn a year. To be clear, we spend close to $11bn a year on fossil-fuel subsidies and we want to spend $368bn on nuclear submarines…The idea that we can’t fund the environment is just false. Everything is affordable, if it’s a priority.”

Permanence

As carbon offsets go up in (wildfire) smoke in Canada, raising criticism about their ability to store carbon long-term, experts say very little research has been done on “permanence” of biodiversity offsets.

Most offset schemes around today guarantee net gains over a two-decade period, says zu Ermgassen, and have a “reasonably long-term” lock-in as contracts. But there are limited mechanisms to ensure that any biodiversity gain is delivered permanently after that. He adds:

“There’s the assumption that biodiversity management will continue in the future, but, obviously, it is too early to evaluate whether or not that’s actually happened. That’s a scientific question.”

In the case of Australia’s “nature repair market”, permanence of credits is not even a factor being considered, according to Hemming, who received no response from legislators when she questioned them about it. She tells Carbon Brief:

“There’s no evidence that the baselines of the proposed biodiversity credits or certificates factor in climate change, like say, species migration or even the impact of climate change in the future. How does a changing climate factor into your method and baselines? What happens when koala habitat burns down or dries out or is flooded? No one has thought ‘perhaps we should answer these questions before we persevere’.”

Regulation, consumption and environmental justice

An overarching observation from critics is the steady march away from environmental and climate regulation towards market-based instruments, such as carbon and biodiversity offsets, that only serve to perpetuate each others’ pitfalls.

To Hache, biodiversity politics are the same as climate politics for rich, western countries. He tells Carbon Brief:

“To avoid putting in place any regulation that would adversely impact your economic growth and short-term competitiveness: that is the overarching objective…All the rest is diverting the conversation away and possibly making a quick buck in the process by creating a new asset class that is exactly the same.”

Zu Ermgassen warns that, if done badly, biodiversity-offsetting could perpetuate colonial inequities and be perceived as countries in the global north “offshoring” their biodiversity conservation to cheap areas in the global south, thereby implementing conservation that excludes local people. That is the “absolute worst-case scenario, although people in this sector are increasingly clued up on equity issues”, he says, adding:

“These frameworks, offsetting markets and compensation markets…all have the potential to be a distraction from what I see as the fundamental problem, which is wildly excess consumption in the global north. And, if done incorrectly, they can be seen as legitimising what is fundamentally unsustainable extraction patterns, especially of the extremely affluent.”

The “single most important thing” for biodiversity, he adds, rather than developing markets that “tinker around the edges and compensate for harms” is reducing those harms in the first place, through reductions in consumption and policies that penalise profiting off ecological damage”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“A nature-positive future is not business-as-usual. We’ve experienced these widespread biodiversity declines for the last five decades. Continuing with that trajectory is not going to solve the problem.”

For Apostolopoulou, there is little evidence that pricing biodiversity guarantees saving species from extinction, but it “does create an opportunity for specific sectors of capital to gain from the destruction or conservation of nature”.

What her research has consistently found is that there is an absence of affected people in mitigation and offsetting decisions. She tells Carbon Brief:

“You cannot have this discussion if we don’t talk to and about local communities and Indigenous populations and place-based strategies and how their life is organised and how they’re related to nature. We need a completely different approach, [not] a top-down market-based [one]. The main idea behind these policies [is that] you cannot fundamentally criticise economic development.”

Where do biodiversity offsets fit into national and international policy?

Biodiversity offsets and credits are still very nascent in multilaterally agreed international law, but are rapidly gaining momentum in national legislation across the world.

For example, biodiversity offsets are included in Target 19 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which covers finance for reversing biodiversity loss in this decade.

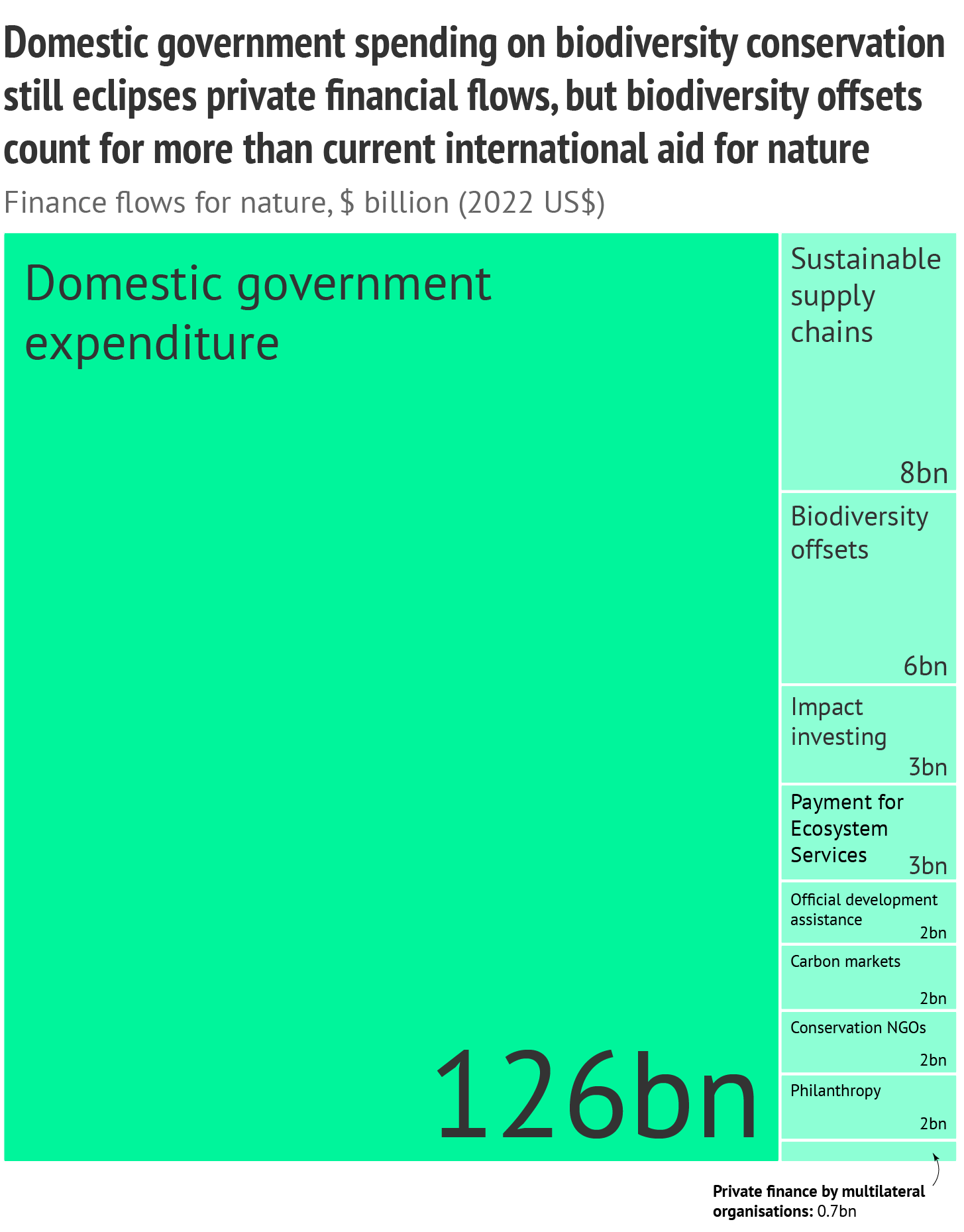

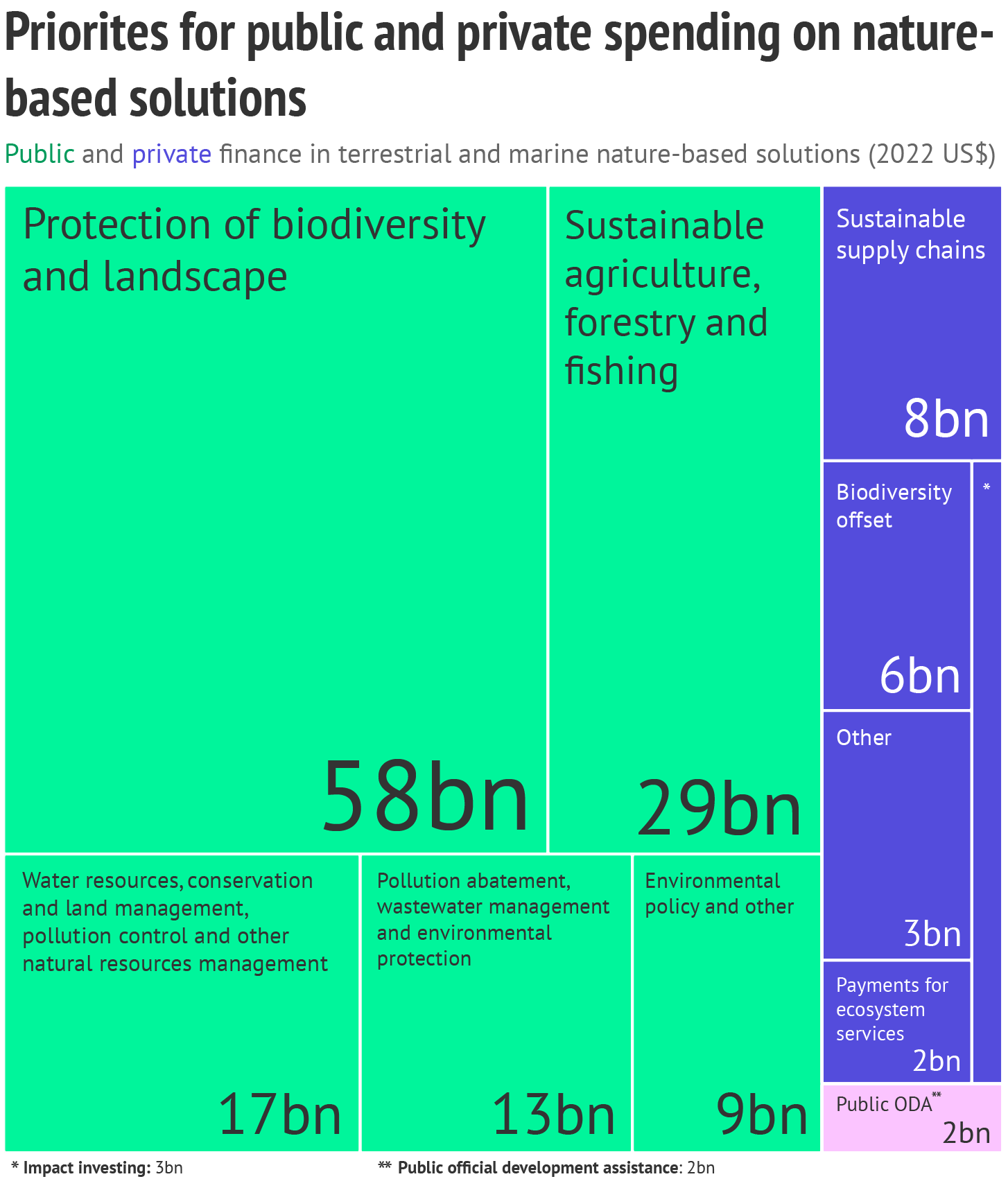

The framework, which aims to “halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030”, calls on countries to mobilise “at least $200bn per year” by 2030 from “all sources” – domestic, international, public and private.

While the call from biodiversity-rich developing countries was initially for “new and additional” public finance for biodiversity in the form of a new fund, this was hotly contested by rich countries, such as the UK, France and Norway.

Instead, the final strategy for resourcing the GBF called for the inclusion of “new and innovative approaches”, such as private capital and blended finance, as well as instruments, such as green and blue bonds.

Lim Li Ching of the Third World Network tells Carbon Brief:

“Although biodiversity offsets and credits have been identified in the Kunming-Montreal GBF as ‘innovative schemes’, the promises of such market-based mechanisms have been overstated…and are likely to fail in delivering biodiversity conservation, restoration or sustainable use, as past experiences show us.”

Importantly, Ching adds:

“There have been human rights abuses because local rights holders, such as Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs), women and youth, are usually excluded from offset areas and only tiny percentages of finance reach them, despite their major role in biodiversity conservation.”

The language from the biodiversity summit mirrors language seen at the climate talks. For example, at COP27, rich countries preferred that “a wide variety of sources” – including private capital and philanthropy – should be pooled into a historic fund for loss-and-damage.

Prof Doreen Stabinsky, professor of global environmental politics at the College of the Atlantic in the US, told Carbon Brief during COP15 that biodiversity and carbon markets were being used by developed countries as part of “a great escape” under both the CBD and UNFCCC. She said:

“There’s nothing in the [GBF] about rich countries actually paying a fair share towards any of their past or present ecological debt.”

The development of biodiversity markets is playing out differently in several countries and blocs.

Carbon Brief examines some of these examples in case studies below.