Various impacts were recorded – ranging from floods ruining fields of corn in Tanzania, through to drought and heat destroying coffee in Vietnam and withering the “famed” Cambodian Kampot pepper.

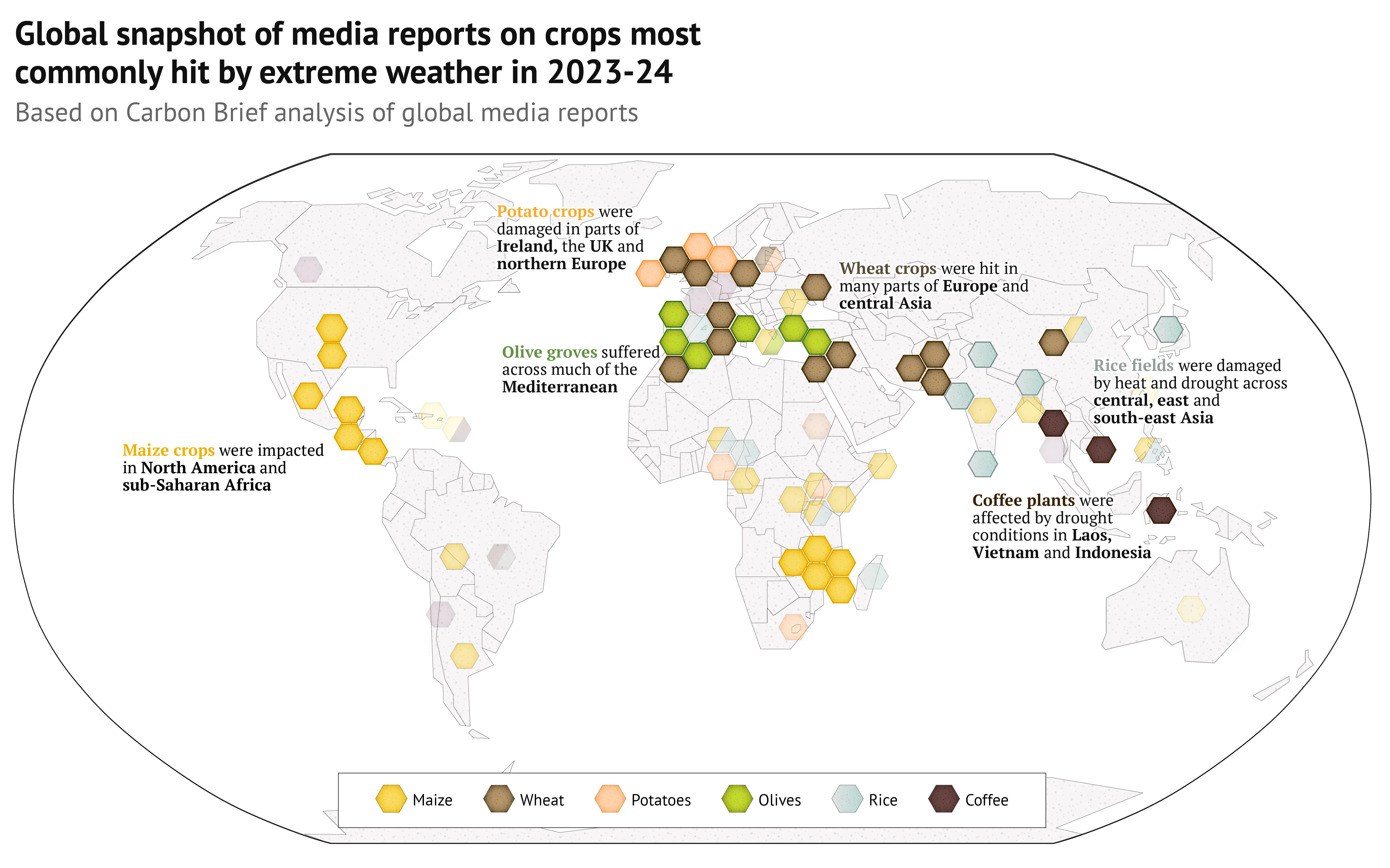

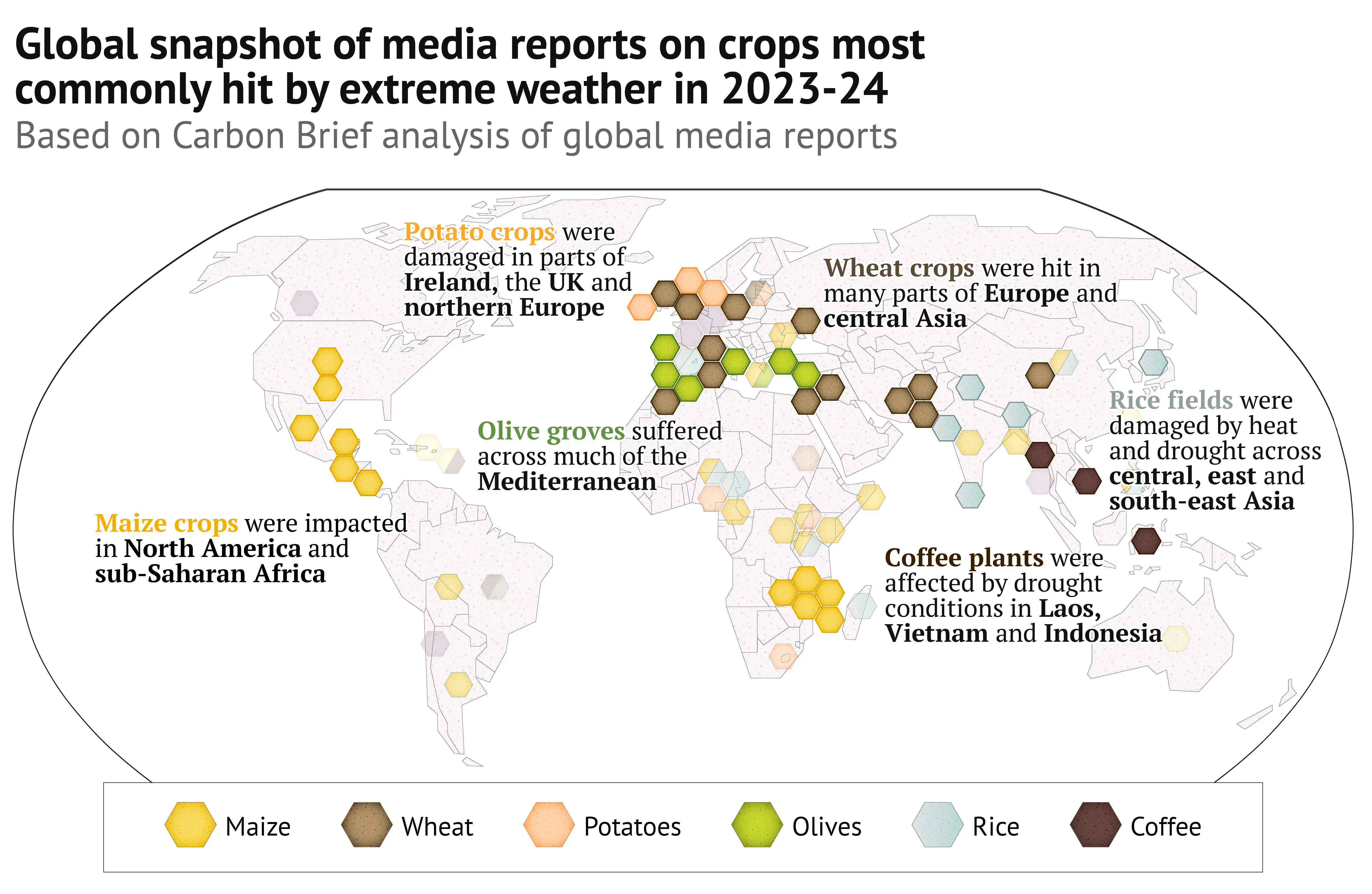

Carbon Brief has used the events found within the media analysis to create the map below, which shows 100 cases of crops being destroyed by heat, drought, floods and other extremes in 2023-24.

Legend

Drought

Drought Rain and flooding

Rain and flooding Heat

Heat Cold

Cold Storm

Storm Wildfire

WildfireExplore the map by clicking on any of the markers for more information.

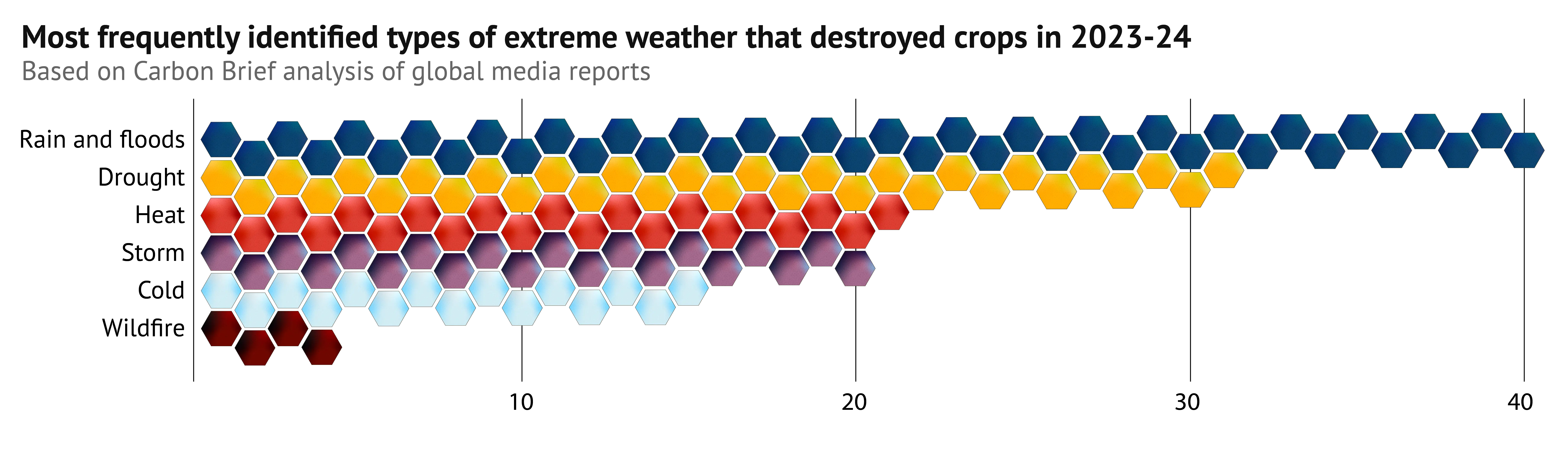

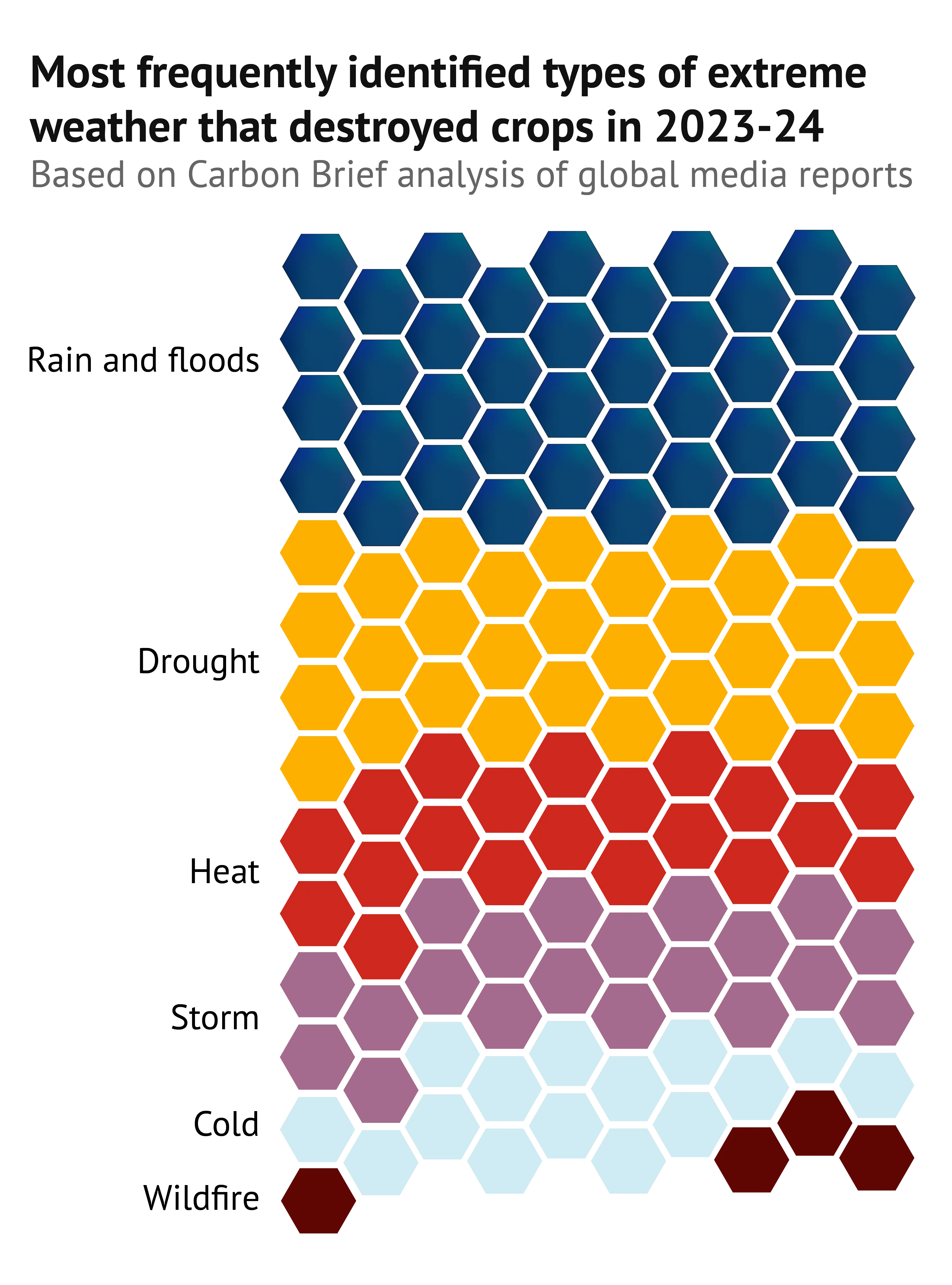

Carbon Brief analysed 100 national and international media reports and information from other sources, such as the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, showing cases of crops being damaged by extreme weather events between January 2023 and December 2024.

It is based largely on English-language reports and, as a result, has geographical gaps in the global south.

Varied impacts of extreme weather on food production

“Sudden food production losses” due to extreme weather events have become increasingly frequent “since at least [the] mid-20th century”, according to the sixth assessment report (AR6) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The report found with high confidence that extreme weather events will push some current food-growing areas “beyond the safe climatic space for production”.

Experts tell Carbon Brief they are concerned about how repeated and intensifying extremes will impact agriculture around the world.

Extreme weather has both immediate and long-lasting impacts for farming. It can reduce crop production, cause variable yields and ruin entire harvests.

For example, a 2012 typhoon destroyed vast amounts of bananas growing in the Philippines.

Dr Monica Ortiz, an environmental scientist and assistant professor at the University of Concepción in Chile, has researched the impact of tropical cyclones on bananas. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It actually took the industry about five years to recover from the really big losses from that particular year.”

In some parts of Nepal, apples now need to be grown at higher altitudes due to changing conditions, says Ananta Prakash Subedi, an assistant professor at the Agriculture and Forestry University in Nepal. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In the mid-hills of Nepal, which is famous for mandarin orange…[the crop is] also being affected badly. Citrus declining and diseases, along with numerous insects are affecting mandarin oranges.”

Climate change and other risks to agriculture – and the way in which these different risks “interact, cascade and multiply” – is something Prof Andy Challinor wrote about in a UK climate risk independent assessment report in 2021.

Challinor, a climate impacts professor at the University of Leeds, says that climate impacts, trade disruptions, geopolitics and other “volatility” all affect food production. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In many cases, it’s the additional risk posed by climate change and the way in which that interacts with other risks that’s really important.

“That seems to be at the heart of a lot of the issues we’re experiencing, and that’s because our food systems don’t have that kind of systemic resilience.

“It is these various disruptions and extremes that are interacting with each other. They’re not always predictable and, certainly, the way in which they interact and produce downstream impacts isn’t predictable – except to say we know we can expect more of them.”

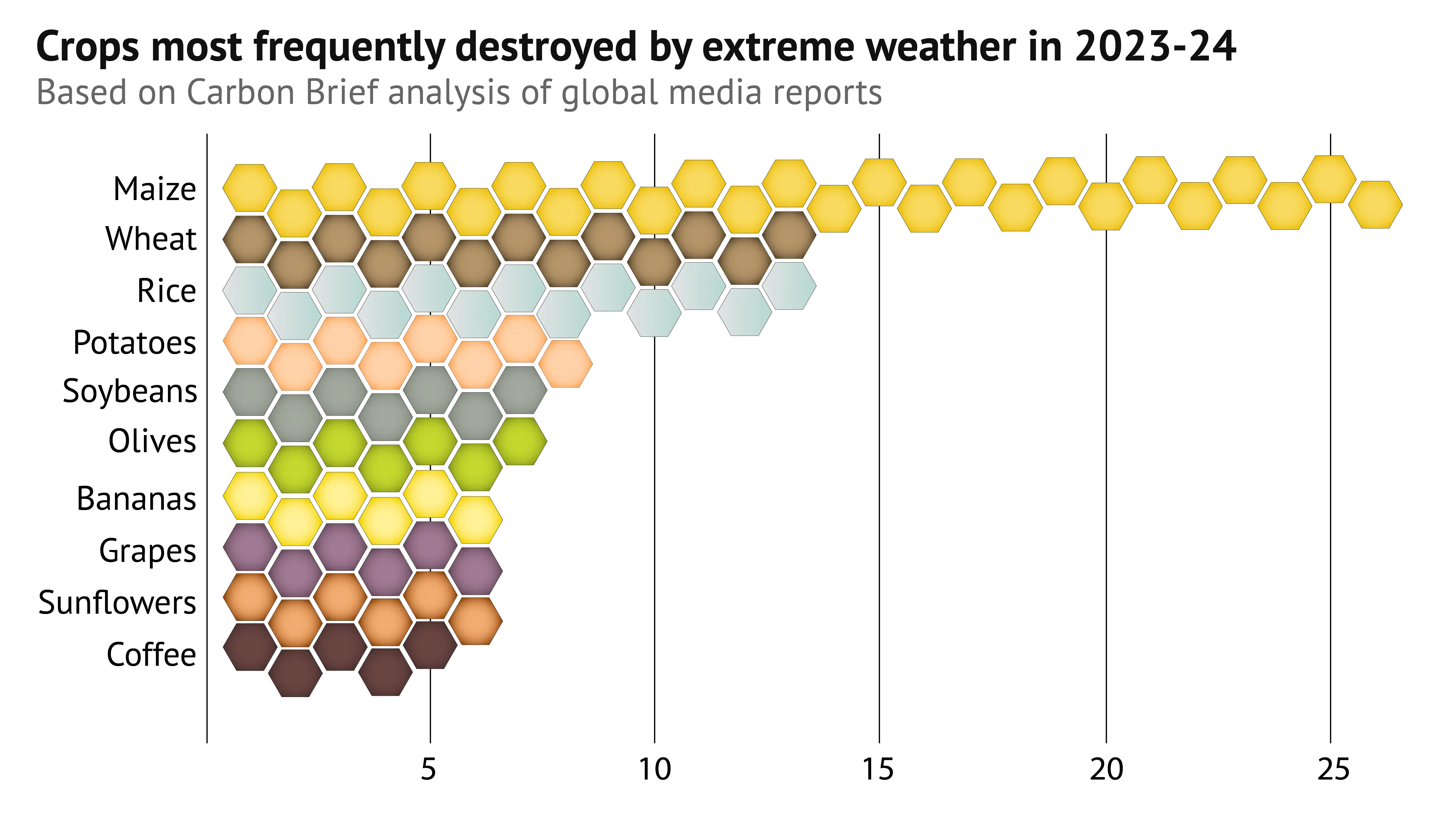

Carbon Brief’s analysis identified dozens of different types of crops destroyed by extreme weather events. The foods have been grouped into categories in the chart below.

‘Double-whammy’ effects

The weather has always played a major role in the outcomes of food production and extremes have invariably been an added, unpredictable difficulty.

This is now exacerbated by human-caused climate change making many of these extremes occur more frequently and with greater intensity.

Some of the events included in the map have been analysed by specific “attribution” studies, which quantify the influence that climate change has had on their severity or frequency.

For example, a World Weather Attribution (WWA) study found that climate change and El Niño made the 2024 heavy rainfall and floods in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul more likely and intense. These floods impacted fields of soybeans, killed more than 150 people and displaced more than half a million.

Extreme weather can also be fuelled by the El Niño weather phenomenon, which occurs when sea surface temperatures heat up in parts of the Pacific.

El Niño was a key driver in the drought in southern Africa in 2024, according to the WWA group. This drought ruined about half of Zimbabwe’s maize crop, BBC News reported in April 2024.

A “double-whammy” of El Niño and climate change impacted Latin America and the Caribbean in 2023, bringing drought, wildfires and other forms of extreme weather, the World Meteorological Organization said. During this time, wildfires tore through vineyards in Chile and drought led to lower production of soybeans, corn and wheat in Argentina, for example.

Other impacts

Carbon Brief has focused on impacts to crops for this analysis, meaning that animal agriculture is not included in the map above.

But extreme weather does impact livestock in many different ways.

More than seven million animals died in Mongolia in the first half of 2024 amid an extreme “dzud” winter event. This was “more than a 10th of the country’s entire livestock holdings”, the Associated Press said.

Dzuds occur when severe, snowy winters follow after a summer of drought. They can cause livestock to either starve or freeze to death. They also lead to unemployment and migration from rural areas.

Dzuds are expected to become more frequent and intense due to climate change as Mongolia faces more droughts in the future.

In the spring of 2023, heat led to a drop in some milk yields in Singapore.

Heat extremes also affect farm workers. High levels of warming could lower agricultural labour capabilities, a 2021 study found. Some farmers and fisherfolk now work at night to avoid intense daytime heat, Grist reported in 2024.

Warmer conditions can also further the spread of diseases and pests that destroy crops, such as locusts.

Changing weather conditions can sometimes benefit crops that thrive in warm conditions. For example, warmer temperatures can potentially help the growth of durian and mango in Malaysia, along with apples and sweet potatoes in Japan.

Climate change could also potentially help crops to grow in areas that were previously unsuitable. Soybeans, chickpeas and grapes may grow better in the UK in future due to global warming, a 2005 study said. Many English vineyards are already thriving.

The map below highlights some of the most commonly impacted crops in Carbon Brief’s analysis – such as maize, wheat and potatoes – and the countries in which their growth was affected by weather extremes in the past two years.

Agricultural adaptation

A temperature rise of 2C by the end of this century would have “large negative impacts” on food production systems around the world, the IPCC AR6 report said.

Land that is currently used for crops and livestock “will increasingly become climatically unsuitable”, while outdoor workers and animals will be “increasingly expose[d]” to dangerous heat stress.

The report also said that models project that climate change will affect the yields of major crops “sooner than previously anticipated”. It warned about the risk of “multi-breadbasket failures”, in which droughts or other extreme weather events occurring at the same time affect crop production in many regions across the world.

There are a number of ways that farmers can adapt to deal with these impacts, but there are also many barriers to implementation and limits to how well these adaptations might work.

Challinor says that building resilience in food systems is key to addressing climate impacts on agricultural production, adding:

“Some of these extremes won’t be able to be avoided, [such as] flooding or entire crop areas being wiped out. So in some areas, we’re going to have to move from smaller coping strategies, adjustment strategies, to transforming.”

Prof Elena Piedra-Bonilla, a professor in environmental economics at Ecotec University in Ecuador, is concerned about the future of small-scale agriculture under climate change. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s very worrying, especially for small farmers…They don’t have enough adaptive capacity for climate change.

“We see the weather shocks that are happening. We have floods, we have drought and it’s more intense…I think it’s necessary to put more emphasis on adaptation [for certain farmers]…especially in countries that are not big emitters. We should try to make efforts for adaptation that is [responding to the extreme weather] happening right now.”

She says many farmers in Ecuador and other parts of South America have little time, finances or assistance to adapt their practices to climate change. As a result, they “often just have to deal with extreme weather as it happens”.

The IPCC AR6 report noted various adaptation practices that are “feasible and effective at reducing climate impacts” for agriculture. These include sustainable resource management, incorporating Indigenous and local knowledge and diversifying crops and species.

But there are financial barriers to putting these in place, with “vastly more public and private investment” needed to fund adaptation in agriculture, fisheries, aquaculture and forestry, the IPCC said.

Just over 4% of global climate finance went to agrifood systems in 2019-20, according to the non-profit Climate Policy Initiative.

Crop insurance, disaster funds and other emergency aid from governments following periods of extreme weather can also help farmers deal with the impacts.

But these, too, have their limitations.

For example, the New York Times reported last year that crop insurance is becoming “prohibitively expensive” and more difficult to access for some US farmers due to climate change increasing the likelihood of crop-destroying extreme weather.

Although climate change will continue to impact food systems in many different ways, Ortiz points to some solutions such as drought-resistant crops. She adds:

“The question is how do we match up the research and technology with what happens on the ground, the accessibility of these technologies, and [also] the social and political environment that agriculture takes place in.”