Two-thirds of the world’s biggest companies with net-zero targets are using “carbon offsets” to help meet their climate goals, Carbon Brief analysis reveals.

(Clicking links with a will display the full glossary term.)

The world’s top fossil-fuel producers, carmakers and tech firms have used tens of millions of carbon credits to claim they have “cancelled out” large chunks of their emissions in recent years, the analysis shows.

This article is part of a week-long special series on carbon offsets.

Carbon Brief finds that just 34 companies have used credits to offset 38m tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2) during 2020-2022, equivalent to the annual emissions of Ethiopia and Kenya combined.

The top users of carbon credits – units each representing one tonne of CO2 avoided, reduced or removed – were Shell (9.9m units), Volkswagen (9.6m) and Chevron (6.0m).

In theory, credits represent emissions savings undertaken on behalf of the buyer – typically, by supporting renewable energy or forest-protection schemes.

In practice, many projects have failed to deliver. Campaigners say the rapidly growing trade is a cheap alternative to real carbon cuts that provides the biggest emitters with a “licence to pollute”.

Carbon Brief’s analysis of the world’s top 50 companies with net-zero targets by market capitalisation sheds new light on the often-opaque world of carbon credits.

Indeed, the analysis shows there is no public information at all on the users of half the credits bought from the top four voluntary offset “registries”.

Other key findings include:

- Fossil-fuel companies and car manufacturers were responsible for more than three-quarters of the offsets used by the top 50 companies.

- Projects in Indonesia (9.2m offset credits), China (6m) and Colombia (5.8m) provided the most offsets.

- The single-largest provider was the Katingan peatland project in Indonesia, which generated 5.4m offsets for these companies – in theory, the equivalent of taking 2m cars off the road.

- Only 8% of the offsets used were from projects that removed CO2 from the atmosphere – predominantly tree-planting.

- Half of the offsets were from REDD+ forest protection projects. A growing body of evidence suggests these projects often overstate their climate impact.

Offset surge

Businesses, organisations and even individuals can purchase carbon “credits” on the voluntary offset market. Each represents one tonne of CO2 that has – in theory, at least – been reduced or removed from the atmosphere elsewhere, by a project such as a windfarm or a preserved forest.

Companies then claim these cuts as their own and use them to “offset” their emissions as they work towards self-assigned climate targets – for example, to become “net-zero” or “carbon-neutral” by a fixed date.

There has been a surge in voluntary offset purchases in recent years, coinciding with societal and political pressure on corporations to decarbonise. In total, 146m credits were “retired” – meaning they were used – from the four largest registries in 2022, more than double the volume just three years earlier.

Sign-up to Carbon Brief’s award-winning newsletters here

At the same time, concerns have been raised by activists and scientists that offsets are providing a cheap alternative to climate action, while delivering negligible emissions cuts.

To understand how major companies are employing offsets, Carbon Brief used Net Zero Tracker to identify the top 50 publicly listed companies, by revenue, that have set themselves net-zero or similar goals. Some 28 have explicitly stated their intention to use offsets, but others use them too, the analysis shows.

Carbon Brief then combined data from three sources to investigate how many offsets have been used by these companies between 2020 and 2022. This draws on a methodology developed by Prof Gregory Trencher, an energy policy researcher at Kyoto University, and colleagues, for a study of offsetting behaviour by four oil majors. (See: Methodology.)

The analysis relied on these alternative data sources because there are significant gaps in the public information available from the registries that “issue” carbon credits, after going through a process of verification. (See: Missing data.)

Overall, Carbon Brief identified 37.8m carbon offsets that were used by 34 of the top 50 businesses to help meet their climate targets. This equates to approximately 5% of the credits on the voluntary market that were used across this three-year period.

Half of the offsets identified in this analysis were used by fossil-fuel companies, primarily Shell and Chevron, and 28% by car companies, particularly Volkswagen.

(The true numbers of offsets could be larger as the analysis firm AlliedOffsets – one of the data sources Carbon Brief has used – notes that it is not able to identify buyers in registry transactions that are completely anonymous for the public. For example, oil major Saudi Aramco – which does not appear in this analysis, is aiming to use 16m carbon offsets annually by 2035 and has already been investing in offsets. This is explained further in the “Missing data” and “Methodology” sections below.)

Sourcing offsets

The Sankey diagram below shows how offsets have flowed from projects around the world into the balance sheets of these 34 major companies.

Where companies buy offsets from

Millions of carbon-offset credits, each equivalent to 1t CO2

The majority of the companies analysed – 41 in total – are based in developed countries, with nearly all of the remainder based in China.

Yet 35.2m of the 37.8m credits they have used are from projects in developing countries, particularly Indonesia, China and Colombia. (The remainder includes 2m credits from developed countries and around 520,000 where the country of origin could not be identified.)

Carbon offsets are often framed as a way to channel private climate finance to the global south by their supporters, including leaders from those countries. However, numerous allegations of harm to local people and global-north companies taking large cuts of the profits have led many to critique offsetting as a damaging and even “neo-colonial” venture.

Some of the biggest offset-generating countries in this analysis have faced considerable problems related to these projects.

In Peru, there have been allegations of exaggerated emissions cuts and displaced communities, Indigenous ways of life have been allegedly harmed in Kenya and the government of Zimbabwe has argued that the state is not benefiting from offset projects on its soil. (See: Mapped: The impacts of carbon-offset projects around the world.)

Nearly all of the offset use in Colombia is due to the fossil-fuel company Chevron, which has a “long history” of oil-and-gas exploration in the nation. This analysis shows that the firm retired 5.8m offset credits from Colombian projects between 2020 and 2022.

A recent investigation by the NGO Corporate Accountability concluded that at least 93% of credits used by Chevron in 2020-2022 – including those from Colombian projects identified in this analysis – were likely “junk”.

Chevron rejected this allegation, pointing out that most of the offsets in question were “compliance-grade” offsets accepted by governments in the regions where we operate”. (Some businesses buy credits from the voluntary market that can be used to comply with local regulations.)

While some of the projects in developing countries are operated by national NGOs and businesses, others are managed by organisations based as far afield as California, Hong Kong and Guernsey.

Of the 2m credits generated in developed countries, two-thirds are from projects in the US. These were nearly all sold to US-based companies, such as Microsoft and JP Morgan Chase.

Here, too, accusations of problematic offset projects are rife. A Bloomberg investigation in 2020 accused GreenTrees, a company that provides 16% of the US credits retired in this analysis, of “taking credit for other people’s trees”. (In response, the company pointed out that independent auditors had repeatedly verified that its forestry project abides by the rules set by the American Carbon Registry.)

Big projects

As the chart below shows, a selection of just nine offset projects, notably the Katingan and Rimba Raya peatland forest projects in Indonesia, have provided a disproportionate amount of the offsets to the major companies analysed by Carbon Brief – 19.3m in total.

Nine offset projects account for half of the credits used

Millions of carbon-offset credits, each equivalent to 1t CO2

Some of these projects, including Katingan, the Cordillera Azul National Park project in Peru and the Kariba forest conservation project in Zimbabwe, have been accused of overstating their emissions reductions.

In each case, the project developer has rejected these allegations, emphasising that the methodologies they use are robust.

Removals vs reductions

Carbon offsets can be issued from a large variety of projects, including solar farms, new forests and cleaner cookstoves for low-income communities. The diagram below shows the offsetting project types favoured by the companies in this analysis.

Offsets from REDD+ forest conservation projects are by far the most popular, with 52% of the total. Other major varieties include hydropower, tree-planting and wind power.

Types of offset credit used by companies

Millions of carbon-offset credits, each equivalent to 1t CO2

The REDD+ scheme for curbing forest loss and degradation was initially designed under the United Nations (UN) to channel climate finance to forest communities in developing countries.

Yet REDD+ projects issuing credits on the voluntary market have come under fire for years from international NGOs and Indigenous groups, who have accused them of links to forced displacements and fraud. There is also a growing body of research suggesting that these projects overstate the volume of emissions they avoid.

There have been extensive efforts among academics to identify which types of offset projects can be most reliably tied to real-world emissions reductions. Emissions-removal projects, where CO2 is physically removed from the atmosphere by planting trees, for example, are broadly understood to produce higher quality offsets.

These projects are not without risk, as when trees are planted their CO2 removal can be undone if they die or burn down, as has happened at offset projects in the US and Spain.

The main alternative is emissions reduction or “avoidance”. This might involve building wind turbines and calculating the emissions saved in comparison to a counterfactual scenario where a coal plant was built.

Many land-based projects, such as forest conservation, are sometimes classed as “mixed” because they involve some CO2 removal but also comparison with scenarios in which land is degraded. Trencher tells Carbon Brief that, in reality, these projects can nearly all be considered as emissions avoidance because there is little additional CO2 being removed.

As the chart below shows, the vast majority – 81% – of the offsets purchased by top companies since 2020 come from “reduction” or “mixed” projects.

Most offsets are based on emission reduction rather than removal

Millions of carbon-offset credits, each equivalent to 1t CO2

Only 8% involved the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. Nearly all of these offsets are from tree-planting projects, with a small number (0.6% of removal-based credits) based on biochar projects.

Tech companies including Dell, Microsoft and Apple tended to use higher proportions of removal-based offsets – with more than half of the offsets on their rosters coming from such projects.

Trencher tells Carbon Brief that tree-planting offset projects also constitute an “ethical problem”, noting that:

“The current model relies on securing cheap and massive land reserves in the global south to offset the polluting lifestyles and businesses of the global north.”

In his view, improving the existing offsetting system requires shifting from the “low-quality and cheap credits” currently on the market towards credits based on technological carbon methods that remove emissions permanently, such as direct air capture.

Several companies Carbon Brief approached, including JP Morgan and Google emphasised plans to move towards such high-durability offsets.

Missing data

In order to conduct this analysis, Carbon Brief relied on a combination of third-party data, company reports and academic research. This is because registries contain significant gaps that make it difficult to ascertain who is using offsets and in what volumes.

Carbon-offsetting cannot function if participants fail to track who is buying and selling credits.

Registries such as those run by Verra and Gold Standard are responsible for keeping track of how carbon offsets are proceeding through the system. Their publicly available databases contain information about who has issued carbon credits and who has “retired” them.

(Nearly 70% of credits retired in this analysis were issued by Verra and 12% by Gold Standard. Of the remainder, 12% came from the UN’s Clean Development Mechanism and the rest were issued by a variety of smaller organisations.)

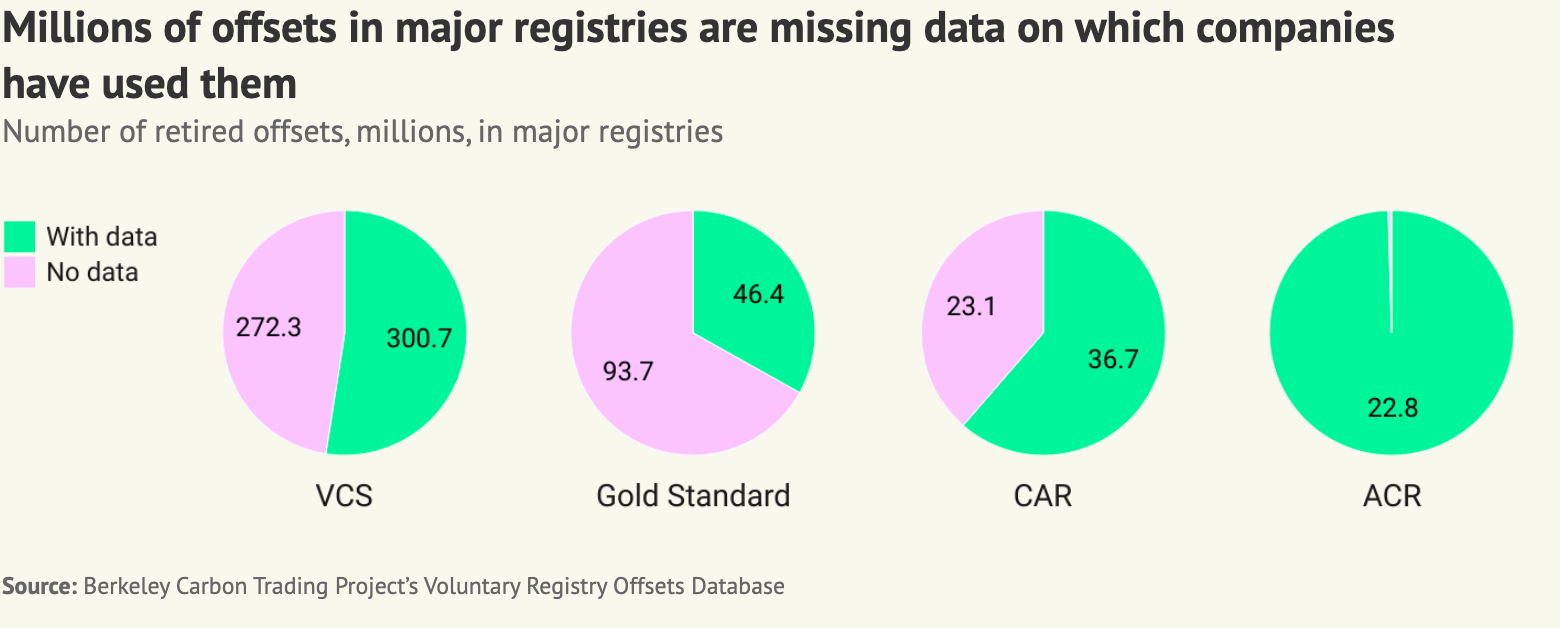

Carbon Brief has analysed data from the four largest voluntary offset registries – American Carbon Registry (ACR), Climate Action Reserve (CAR), Gold Standard and Verra (VCS) – as recorded in the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project’s Voluntary Registry Offsets Database.

This analysis reveals that 23% of the 290,843 retirement transactions listed contain no information at all about which company or other entity is using the offsets in question. These transactions cover roughly half of the 796m retired offset credits listed.

The breakdown of how many retired offsets in each registry are missing data can be seen in the charts below. Of the four, only ACR consistently includes details of who has used its offsets.

Even when registry entries do include information, often the company or organisation is not readily identifiable. It might be listed under an alternative name or the name of a specific project or activity.

“The registries do not require companies to disclose the credits they purchase,” Dr Barbara Haya, director of the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, tells Carbon Brief.

As Trencher and colleagues note in their paper, in relation to data gaps for fossil-fuel company retirements:

“In cases where a major does not list its name in connection to a specific credit retirement, it is unclear whether this is done to escape public scrutiny or because credits were purchased via intermediaries, procured directly from self-developed projects, or provided to customers.”

Pedro Chaves Venzon, international policy advisor at trade body the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), acknowledges that tracking offset use is an issue. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Companies need to register their purchases and retirements. That’s the basis for the registries in the market to work. However, as the voluntary carbon market counts on multiple private standards, each one with their own registries working independently of each other, it is difficult to track such information.”

A spokesperson from Verra tells Carbon Brief that buyers have to state when they have retired credits and who is counting the retirements towards their targets, but they are not obliged to make that information public.

A Gold Standard spokesperson says they do not require buyers to disclose their names and, even if they do, they are not obliged to make it public:

“We want to be careful not to have a system that enforces disclosure onto individuals or may cause problems for some entities – such as government departments who can’t necessarily annotate or ascribe on a third-party platform.”

Carbon Brief also reached out to CAR about its data gaps, but did not receive a response.

Methodology

Carbon Brief obtained a list of the top 50 companies globally by revenue that have announced “net-zero” or similar pledges from Net Zero Tracker (including “carbon negative”, “carbon neutral”, “climate neutral” and “zero-carbon”). The platform also collects data on whether companies have explicitly stated their intention to use carbon offsets to reach their climate goals. Most of the company entries were last updated around the end of 2022 or start of 2023, which roughly aligns with the timespan covered in this analysis.

Owing to gaps in available carbon-offset registries that make it difficult to assess which organisations or individuals are responsible for retiring which offsets, Carbon Brief turned to third parties to collect the relevant data. The methodology for this analysis draws from a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change by Trencher et al., which looked exclusively at offsets purchased and retired by four oil majors – BP, Shell, Chevron and ExxonMobil.

Carbon Brief requested the total retirements, by project, for the period 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2022, from analysis firm AlliedOffsets. This data is extracted from retirement data recorded in 20 voluntary offset registries, which the company matches to buyers. The company matches up registry data on offset retirements with corporate buyers, but it is not able to identify completely anonymous buyers.

This data was then supplemented with information extracted manually from company questionnaire responses submitted to the CDP for climate change in 2020-2021. (This corresponds with CDP reports labelled as “Climate Change 2021” and “Climate Change 2022”, which contain the previous year’s data.) CDP data for 2022 was not available at the time of analysis. If the CDP reported offset retirements that exceeded those in the AlliedOffsets data, Carbon Brief included the difference between the two values in the dataset. In cases where companies have changed their names or merged over the study period, both names are listed.

A small number of companies have chosen not to provide data to the CDP and also did not have any data recorded by AlliedOffsets. This could explain why some companies, such as Saudi Aramco, are known to be purchasing carbon offsets, but do not feature in this analysis.

In their analysis, Trencher et al. also searched through company documents and retirements recorded in the four main registries in the voluntary carbon market to find additional credits. This was beyond the scope of this analysis, but Carbon Brief included a handful of additional retirements identified by Trencher et al. using this method for BP, Shell, Chevron and ExxonMobil.

To obtain additional information beyond project name, number of offset retirements and, in some cases, project ID, Carbon Brief used the Voluntary Registry Offsets Database produced by the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project. This filled in missing information about project type etc. when projects were registered under the four main registries – American Carbon Registry (ACR), Climate Action Reserve (CAR), Gold Standard, and Verra (VCS). The UN’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) registry provided this information for CDM credits.

Company responses

Carbon Brief contacted the top 50 companies by revenue to give them an opportunity to contest any errors in the offset-retirement data, provide any missing data and comment on how they were using offsets to reach their climate targets. Only 11 responded with information and only Samsung identified credits that had been falsely attributed to it – 288 in total.

Shell, Amazon, Deutsche Telekom, Samsung and Google said that offsets would only be used on top of efforts to avoid and reduce emissions as much as possible. BP said it intends to reach its 2030 emissions target without offsets, but they “may help us to go beyond those aims”. ExxonMobil said it “may employ high-quality emissions offsets where technology and policy advancements are still needed”.

Microsoft provided details of projects and credits it has “contracted” in its “carbon removal portfolio” during 2020-2022. However, the documentation states that these credits would not all be used towards the year in which they have been reported. Therefore, Carbon Brief has not captured all of them in this analysis, which focuses on offset retirements within this time period.

Some companies said their offset purchases were not being counted towards their net-zero targets. Samsung said its purchases were not used to offset its carbon emissions. Similarly, people familiar with the matter explained that only the large retirements from the Oneida Herkimer Landfill project were used for Google’s corporate-emission reporting, while small purchases were merely “one-off” cases. Amazon also does not make any claims about neutralising its emissions with offsets.

Of those top-50 companies not included in the analysis, Exor and Saudi Aramco both indicated they had purchased offsets, but did not provide details of the projects in question.

This article is part of a week-long special series on carbon offsets.